In his early weeks, Hotham spent time getting acquainted with Victoria. In August, accompanied by Lady Hotham he ventured to the goldfields to observe conditions, and in his three days at Ballarat found the diggers to be respectful, loyal and enthusiastic. [1] The Ballarat Times optimistically reported:

A bold, vigorous and far-seeing man has been amongst us, and the many grievances and useless restrictions by which a digger’s success is impeded will be swept away. [2]

At Geelong on 15 August, Hotham spoke of the need for government borrowing to finance public works and said that his review of spending would not result in such works being curbed describing rumours that it would as ‘twaddle’. He referred to Victorian’s new constitution saying that it was based on the principle that power came from the people, a principle that would guide his administration.

I stand between two systems of government—the present and the pregnant: and in all probability it will shortly be my duty to wind up one and commence with the other. The people of this colony have adopted one of the most liberal constitutions, compatible with monarchy, which a people could have; it is a constitution of your own choosing, formed by your representatives…But when you adopted that Constitution, you adopted with it the principles from which it springs—that all power proceeds from the people. [3]

‘Canvas Town’: Melbourne in the mid-1850s

For some, his words suggested a liberalising of government policies but for conservatives, they seemed to augur the end to the privileges of the ruling class. In reality, Hotham was expressing a paternalistic concern for the welfare of the people as a whole rather than supporting the expansion of democratic principles. At Bendigo, meetings were held in late August to prepare resolutions for the Governor’s visit. [4] When in early September, Hotham visited Bendigo he was presented with a petition calling for the suspension of the license fee and decided to meet the diggers and address them arguing that ‘liberty and order’ had to be paid for but omitted to say that payment was increasingly achieved through the presence of military force.[5] What Hotham saw in all the goldfields he visited was partial and it was this that strongly influenced his future decisions. The Argus warned after his visits to the goldfields:

In the diggers he has seen an assemblage of men of infinite varieties of character and temperament; who have been greatly aggrieved in many respects and are neglected to this day. He has seen their numbers and heard their cheers, which, with true devotion to the lady whom he represents, he has put down to their ‘loyalty’. But loyalty has a wide as well as a narrow definition…it is not the unreasoning loyalty of a pack of slaves, reared in the habit of deferential submission to authority, whatever its quality or effects may be… [6]

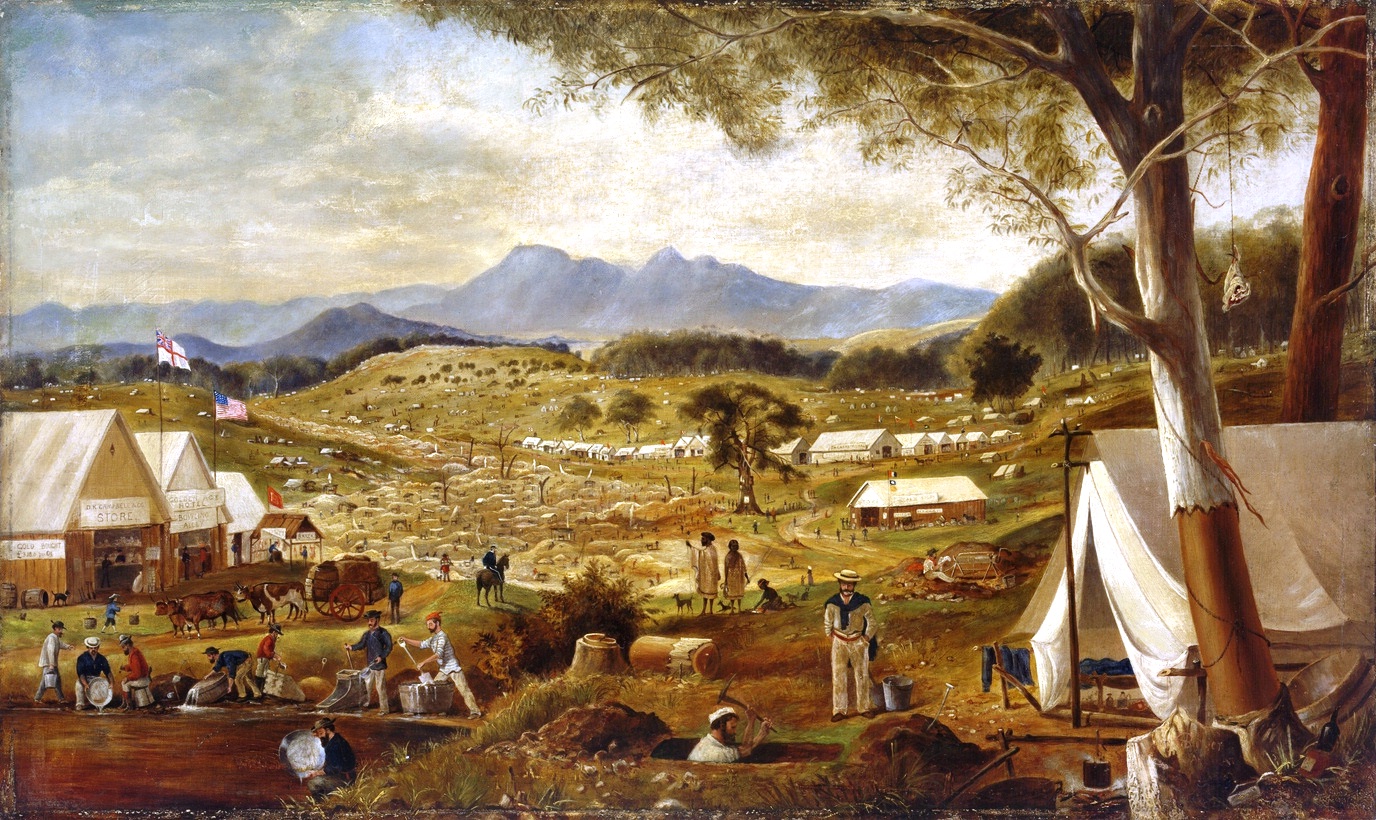

Gold diggings, Ararat, Victoria, c1854

Hotham was shown only the richest claims and seeing the diggers in holiday mood, in mild spring weather, gained an ambiguous impression of their way of life and their prosperity. During his three months in the colony, Hotham had been shown evidence of its wealth but this picture of affluence on the goldfields was one-sided. Alluvial gold had been largely exhausted by 1853 and gold could now only be obtained by deep shaft mining, something that Hotham observed at both Bendigo and Ballarat.

The gold at Ballarat is obtained by deep sinking, in some cases the shaft is 180 feet deep – the digger then encounters slate in which the gold is found. The miner of Ballarat must be a man of capital, able to wait the result of five or six months toil before he wins his prize. For this reason he will always be a lover of order and good government and, provided he is kindly treated, will be found in the path of loyalty and duty. [7]

The yield from the goldfields was significantly lower in 1854 than in the previous two years and although there were still occasional rich strikes, the ‘golden age’ was coming to a close. Diggers could no longer move as easily from field to field and this made them more sensitive to license hunts and more willing to organise resistance. This had a depressing impact on urban investors who had risked their capital in insecure business ventures and shopkeepers who had imported merchandise they now could not sell. Bankruptcies increased, businesses collapsed and men were thrown out of work. [8]

The consequences of the over-importation have been most disastrous to this community. At first, when the glut caused a great depreciation in value, many speculators and retail traders purchased large quantities of goods, to hold for a rise; but the continued arrivals have caused an enormous further depreciation, and the speculators have suffered heavy losses. To this cause is to be attributed many insolvencies. Again, the universal system of forced sales and great sacrifices at auction, have very seriously injured legitimate business, both wholesale and retail, disappointed fair expectations, and caused a ruinous depreciation of stocks; so that many houses of previous good trading and excellent prospects have been unable to meet their engagements.[9]

Hotham’s observations led him to conclude that most of the diggers were sufficiently prosperous for the license to be described a ‘trifling sum’, in his despatch to Earl Grey and their expressions of loyalty convinced him that they were law-abiding citizens. [10] In reality, most diggers struggled to survive in a harsh and unyielding environment where the irritation of intrusive license hunts increased their hostility towards the authorities. Despite what occurred later, Hotham appears to have recognised this:

I deem it my duty to state my conviction, that no amount of military force at the disposal of Her Majesty’s Government, can coerce the diggers…by tact and management must these men be governed; amenable to reason, they are deaf to force, but discreet officers will always possess that influence which education and manners everywhere obtain. [11]

Samuel Thomas Gill, Mount Alexander goldfields, 1852

If Hotham had misunderstood the true situation on the goldfield, the diggers had equally misread the Governor’s intentions. On his return to Melbourne, Hotham was again confronted by Victoria’s precarious financial position and, faced with the urgent need to generate revenue turned to the gold license. Although he believed that there should be a more equitable tax on gold until changes could be made it was his duty to enforce the existing law. He was not persuaded by arguments of digger hardship especially as the fee had been reduced the previous year and maintained that failure to pay was the result of the inertia of the goldfield officials who only carried out license checks two or three times a month.

On 13 September, Hotham ordered that the ‘digger hunts’ should be conducted twice a week. This was certain to provoke an angry response from the diggers. Hotham however, was largely insulated from daily life on the goldfields.

He [Hotham] has not hitherto had proof of what commissioners very often are. He has only met them at dinner parties, at exhibitions and in parlors. He has yet to know the character of the creatures among the diggers to see them discharging their gentlemanly and agreeable duties of exacting a tax and making prisoners of defaulters… [12]

Local Commissioners made weekly reports to the Chief Commissioner in Melbourne who then informed the Governor of any developments considered important. Minor confrontations with diggers were probably played down by local officials who wanted to appear to be maintaining effective control. In addition, until the telegraph line from Melbourne to Geelong was completed in December 1854, all communication between the goldfields and Melbourne were carried by despatch riders who took over 30 hours to reach the metropolis. This lack of information and delays in receiving current intelligence meant that Hotham thought that reactions to his instructions were little more than an expression of irritation.

Lambing Flat miners’ camp c1860

Hotham’s Geelong speech in August hinted at liberalisation of government but his tightening of the license fee and reforms in the public services suggested that he was conservative and authoritarian. Many in Melbourne hoped that his speech at the opening of the new session of the Legislative Council on Thursday 21 September would clarify his position. [13] They were disappointed. Hotham’s speech was brief, did not mention land sales, the digger’s license or the influx of convicts and did little to add to his standing in the colony. [14] There appear to be two reasons for this. [15] He had become increasingly aware of the complexity of the problems he faced and may have felt he needed more time before publicly stating his policy on important issues. Also, his decision largely to ignore the Executive Council and take over routine administration himself was already having a negative effect. Instead of dealing with the daily mountain of correspondence, Hotham needed time to prepare his speech and take the advice of individuals who understood local issues better than he did. He only slowly recognised that there were individuals in Melbourne with ability and judgement and gradually began to take advantage of their support. Three men were particularly important. William Stawell, the Attorney-General and member of the Executive Council since 1851 saw himself as a liberal but many of his ideas were distinctly conservative. [16] John O’Shanassy was one of the government’s severest critics, supported the diggers in their demands for change in the license system and for access to low-priced land but Hotham found his advice invaluable. [17] Finally, John Pascoe Fawkner was a member of the Legislative Council and seen as the ‘tribune of the people’ because of his sympathies for the poor and strong opposition to squatters as a class. [18] His political advice could not be ignored.

Bendigo had been the centre of disturbances in late 1853 but these, like those in other goldfields, had died away in the early months of the following year. Yet, in late June 1854, there was a further disturbance focussing digger anger not on the license fee but the Chinese community. [19] There was growing racial tensions on the diggings where there were 3,000 Chinese out of about 18,000 men and the proportion of Chinese to European was steadily increasing.[20] William Denovan, a Scot who had arrived in Victoria in 1852 and had already achieved some prominence as an advocate of diggers’ rights, began an anti-Chinese movement in Bendigo and organised a public meeting for 4 July with the object of driving the Chinese off the goldfield.[21] The meeting was postponed because it clashed with American Independence Day celebrations but the movement continued with a large public meeting on 10 July.[22] Nonetheless, it crystallised some of Hotham’s ideas on the nature of goldfield disturbances though additional police were also sent from Mount Alexander to Bendigo to quell any further disturbances: the good sense of the majority of diggers and the need to deal decisively with a troublesome minority. [23] In mid-October 1854, a Goldfields Reform League was again established at Bendigo in response to the renewal of license hunts and plans were made to extend it to other fields. [24] Its approach, like the agitation the previous year, remained grounded in moral force with a plan to petition the British Government directly. William Howitt summed up the deteriorating situation in the following terms:

With the whole population of the diggings everywhere as familiar with these outrages and arbitrary usages of the gold Commissioners and police, as they are with the daily rising of the sun, the Governor flatly asserted that no such mal-administration existed…This put the climax to the public wrath. When the Governor of the colony showed himself so thoroughly ignorant of the real condition of its population, it was time for that population to make such a demonstration as should compel both inquiry and redress. [25]

[1] Hotham to Sir George Grey, 18 September 1854, reported his official visit to the goldfields.

[2] Ballarat Times, 2 September 1854.

[3] ‘Sir Charles Hotham’s Reception at Geelong’, Argus, 17 August 1854, pp. 4-5.

[4] ‘Bendigo’, Argus, 1 September 1854, pp. 4-5, details the resolutions passed at a mass meeting on 28 August.

[5] ‘Bendigo’, Argus, 8 September 1854, p. 6, ‘The McIvor Diggings’, Argus, 12 September 1854, p. 4.

[6] ‘The Excursion to the Gold-Fields’, Argus, 13 September 1854, p. 4.

[7] Hotham to Sir George Grey, 18 September 1854.

[8] There may have been unemployment in some areas of Victoria but in others there was a labour shortage. ‘The Unemployed: To the Editor of the Argus’, Argus 19 October 1854, p. 5, offered work to twelve men at 35 shillings a week plus rations on a farm three miles from Ballarat.

[9] ‘The Colony of Victoria’, Argus, 23 November 1854, p. 4.

[10] In Bendigo, there was considerable anger at Hotham’s failure to mention reform of goldfield management in his speech opening the Legislative Council on 21 August: Argus, 2 October 1854.

[11] Hotham to Sir George Grey, 18 September 1854.

[12] ‘Bendigo’, Argus, 21 October 1854, p. 6.

[13] ‘The Legislative Council’, Argus, 22 September 1854, p. 4.

[14] ‘The Governor’s Speech’, Argus, 22 September 1854, p. 4.

[15] Ibid, Roberts, Shirley, Charles Hotham, p. 127.

[16] Francis, Charles, ‘Sir William Foster Stawell (1815-1889)’, ADB, Vol. 6, pp. 174-177.

[17] Ingham, M., ‘Sir John O’Shanassy (1818-1883)’, ADB, Vol. 5, pp. 378-382.

[18] Anderson, Hugh, ‘John Pascoe Fawkner (1792-1869)’, ADB, Vol. 1, pp. 368-370, and Anderson, Hugh, Out of the Shadow: The Career of John Pascoe Fawkner, (Melbourne University Press), 1962.

[19] McLaren, Ian F., The Chinese in Victoria: Official Reports and Documents, (Red Rooster Press), 1985.

[20] ‘The Chinese on Bendigo’, Argus, 7 June 1854, p. 4, ‘Bendigo’, Argus, 22 June 1854, p. 3, ‘Bendigo’, Argus, 29 June 1854, p. 4, chart the emergence of the anti-Chinese movement in Bendigo.

[21] ‘William Dixon Campbell Denovan (1829-1906)’, ADB, Vol. 4, pp. 55-56.

[22] ‘The Anti-Chinese Movement’, Argus, 15 July 1854, p. 3.

[23] ‘Mount Alexander’, Argus, 12 July 1854, p. 3.

[24] ‘Bendigo’, Argus, 16 October 1854, p. 6.

[25] Howitt, William, Land, Labour and Gold or Two Years in Victoria with visits of Sydney and Van Diemen’s Land, 2 Vols. (Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans), 1855, Vol. 2, pp. 2-3.