My blog looks at different aspects of history that interest me as well as commenting on political issues that are in the news

Saturday 23 April 2016

Vicars and Tarts!! Well almost

Tuesday 1 March 2016

Breaking the Habit: A Life of History

- Paperback: 184 pages

- Publisher: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, (1 March 2016)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1530295238

- ISBN-13: 978-1530295234

Sunday 10 January 2016

The Chartists, Regions and Economies

Tuesday 25 August 2015

Annie Besant (1847-1933) : la lutte et la quête

My appallingly bad yet typically English 'franglais' will never do justice to what is an elegantly written and much needed study of Annie Besant. Until now, we have had to rely on Anne Taylor's sound, if partial, biography published in 1991 but no longer. There is some irony in having what must now be regarded as the best available study of Besant's life written by a historian of British history in France. This reflects the lamentable ignorance of most students and many historians of the diversity of her long life and the central role that she played in developing notions of feminism between the 1870s and 1930s. Apart from her involvement in the Match Girls' strike in 1888, Annie barely figures in British consciousness. Yet, either as a direct participant or a dominating influence, she was a pervasive player in improving the status and opportunities for women through education, birth control, workers' rights, theosophy...I could go on. The Pankhursts were important and are justly feted but their role was, until 1918, largely limited to the suffrage question and geographically limited to Britain even though they travelled widely within Britain's Dominions. Annie's struggles to improve the inequalities of women was far broader and, you could argue, far more influential globally, especially in the cause of Indian independence.

This is a book that needs to be read by those concerned with the development of feminism, radicalism and socialism, free thought and theosophy and anti-colonialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It provides a nuanced study of a figure whose importance in British and global history--rather like that of Sylvia Pankhurst--has been under-estimated. Well, no more.

Friday 21 August 2015

Review of Localities, Spaces and Places

Chartism: Localities, Spaces and Places, The Midlands and the South, Richard Brown, Authoring History, 2015, paperback, 403 pp., ISBN 9781501017247

This volume focusing upon the local and regional dimension of Chartism in the Midlands and the South, is Richard Brown’s sixth excursion into Chartism, which with a sequel print volume encompassing the North of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, will provide an extensive and unprecedented analytical survey by a single author of Chartism from a regional and local perspective. As Chartist historian Stephen Roberts has commented such ‘a comprehensive survey of the Chartist Movement, region by region, will be of immense value to all students of Chartism’ since the intended scope of the two volumes and unified Kindle version is ‘truly astonishing’. Not since the ground-breaking collection of essays edited by Asa Briggs in 1959, which E.P. Thompson observed brought us ‘closer to the local roots of Chartism than any previous study’ and which stimulated a myriad of further local studies, has there been a more considered, in-depth, attempt to re-visit this dimension of Chartism. Indeed, since the 1980s, influenced particularly by the controversial intervention of Gareth Stedman Jones in the historiographical debate, the focus of Chartist studies shifted priorities sharply towards considerations of Chartism as a national political movement. Brown’s contention is that both dimensions remain vital to understanding this extraordinary movement. ‘Is it better’, he asks, ‘to see Chartism as a network of semi-autonomous political organisations over which national control was limited rather than a unified political movement?’ His answer is emphatically, that ‘neither one nor the other’ approach will suffice and that a combination of both approaches is now necessary to understand the full impact of this momentous movement on the history of Britain at every level. Chartism, he concedes, ‘may have been a national, political movement but it was grounded in the experience of its local activists as much, and perhaps arguably more than through grandiloquent oratory and the organisational structures of its national leaders’.

Brown engages elegantly and informatively with the historiography of local history in his opening chapter to explain how ‘local and regional considerations, linked to prevailing social and economic conditions played a major role in the ways in which the movement developed nationally’. For example, he argues that the strikes of 1842 arose ‘not from the decisions of national leaders but from the intensity of local anger and frustration at the inequities of local economic structures’. He also draws upon recent writers, notably Katrina Navickas, who have explored the significance of space and place in the development of grassroots radical politics, arguing that recognition of the centrality of space to human experience is ‘fundamental in understanding how and why Chartism developed and exchanged information and ideas within communities, localities, regional and national locations within Britain as a whole’.

Each exploration of regional and local dimensions in subsequent chapters is prefaced by an in-depth socio-economic profile of the locality presenting a rich tapestry focusing upon ‘how Chartism played out regionally and locally reinforcing the point that local priorities and political agendas did not always correspond with those put forward nationally and that, although the national leadership developed principles and policies, operational details were frequently left to local leaders and organisations’. This timely and illuminating study is a poignant and worthy tribute to the author’s wife who died shortly before this volume was completed. It will enrich understanding of Chartism as a national movement, whilst ‘drawing attention to the tensions between the aspirations of the Chartist national leadership and leadership at the local level’, thereby providing an indispensable overview to researchers seeking to understand how the Chartist movement played out in their own particular locality or region.

John A. Hargreaves

Saturday 25 July 2015

‘Revolutionary Chartists – From Whom May Heaven Protect Us’

‘Revolutionary Chartists – From Whom May Heaven Protect Us’ – Cambridge Independent Press, 12 January 1856.

The publication of Chartist Studies, edited by Asa Briggs, in 1959 launched a flurry of research into the Chartist localities. Whatever William Lovett and his friends were up to in London was for the time being set aside. What was going on in Sheffield, Norwich, Brighton and a host of other places was what mattered now. In the Amateur Historian Dorothy Thompson issued a clarion call for local investigations, offering guidance on how to frame that research and on the sources that could be consulted (That essay has recently been reprinted in THE DIGNITY OF CHARTISM). And so articles in local history journals and M.A and Ph.D theses began to appear. Small saplings soon became dense woods. As the years passed, we learned more and more about Chartist activities in the localities. The peak of all this local research was in the 1960s and 1970s, but it continued after that point until we reached the point where we now are: there is no local Chartist stone undisturbed.

Anyone who wants to read all these articles and theses will need to lock themselves in the stacks of a university library for a fortnight and make very good use of inter-library loans. The material is that scattered. The good news is that such extreme measures are no longer necessary. Happily, Richard Brown has embarked on a two-volume project to survey all the Chartist localities. The first volume has just been published. CHARTISM: LOCALITIES, SPACES AND PLACES, Volume 1 examines London, East Anglia, and the Midlands. The rest of the country will be covered in the second volume, due next year. The first thing to say about this first volume is that it is extremely detailed. Anyone interested in what the Chartists in Suffolk or Worcestershire or Derbyshire will almost certainly find the answers they seek. A notable strength of Brown’s work is the depth of his research. Whilst he has, of course, delved into the many essays that have been published about local Chartism, he has also returned to the primary sources, particularly newspapers. This first volume is an extremely useful addition to the study of Chartism. It is thoroughly-researched, clearly-researched and, above all, very handy.

Monday 13 July 2015

Chartism: Localities, Spaces and Places, The Midlands and the South

Just Published

This, the third part of the series, looks at Chartism from the grassroots. Although I originally intended to deal with the local roots of Chartism in one book, the scale of the project necessitated dividing it in two. Although there is inevitably overlap with Chartism: Rise and Demise, these books focus on how Chartism played out regionally and locally reinforcing the point that local priorities and political agendas did not always correspond with those put forward nationally and that, although the national leadership developed principles and policies, operational details were frequently left to local leaders and organisations. Is it better to see Chartism as a network of semi-autonomous political organisations over which national control was limited rather than a unified political movement? Should we see Chartism as a national debate over the exclusion of the working-classes not simply from the parliamentary franchise but from playing any role in determining the future direction of society, the economy and cultural aspirations? The answer is neither one nor the other but both. The first volume covers southern England and the Midlands. The opening chapter examines Chartism in its local and regional context and how it related to different places and spaces, issues explored in greater detail in the remainder of the book. Chapter 2 examines Chartism in London and the South. Chapter 3 looks at East Anglia, an area of agricultural labour where industrial employment was based largely on the products of farming. Economic and social conditions were not conducive to the development of a mass regional movement. Dealing with the Midlands in one chapter would simply have been too large and consequently I divided it so that Chapter 4 examines the largely agricultural counties while Chapter 5 focuses on those counties where manufacturing and mining were predominant. A Postscript brings the first volume to a conclusion. The second volume looks at northern England covering Yorkshire and the North-East in Chapter 6, Cheshire, Lancashire and the North-West in Chapter 7 and at Scotland, Wales and Ireland respectively in Chapter 8, 9 and 10. It also includes the synoptic concluding chapter.

Sunday 26 April 2015

The Dignity of Chartism

Saturday 13 September 2014

Book review--Chartism: Rise and Demise

Chartism: Rise and Demise, Richard Brown, Authoring History, paperback, 2014, ISBN 9781495390340

Chartism, the mass petitioning movement for universal male suffrage, conveniently punctuated with intense bursts of activity around its three national petitions of 1839, 1842 and 1848, appears deceptively familiar to many students. These three fairly distinctive phases of the movement, have readily promoted analytical narrative approaches from R.G. Gammage, via Mark Hovell, J.T. Ward and Malcolm Chase, which have been supplemented by more thematic explorations of other aspects of the movement by a host of prominent historians who have focused on the roles of the government and public order (F.C. Mather); women and the family (David Jones and Dorothy Thompson) and individuals like Feargus O’Connor (Donald Read, Eric Glasgow and James Epstein) and Ernest Jones (Miles Taylor). Richard Brown, in a richly nuanced approach, deftly weaves into his narrative, which broadly follows the conventionally phased structure, discussion of these and many other themes. He explains, for example, how cultural dimensions of the movement though often divisive helped to sustain its momentum in the late 1830s and 1840s and indeed beyond. He also provides a more explicitly historiographical perspective than Malcolm Chase, which students will find particularly helpful, and takes a generally more sympathetic view of O’Connor than some other recent writers, recognising the Chartist leader’s failings, but attributing the successful development of the mass platform which underpinned the movement largely to his abilities as a platform speaker.

Brown’s three-volume review of Chartism, of which this is the second volume, is based predominantly but not exclusively on the undiminishing secondary literature of the movement, supplemented by some pertinent references to contemporary newspapers and archival evidence where appropriate to offer fresh insights into the movement. Brown readily acknowledges his debt to previous writers in the field commenting that Chartism has been exceptionally rewarded by ‘so many good historians who have taken up the Chartist mantle and whose innovative thinking has made the subject so popular’. Succinctly encapsulated within the title Chartism: Rise and Demise Brown’s aim is to give ‘greater attention to the radical context in which Chartism developed’ explaining why it emerged as a widespread political movement in the late 1830s and how it peaked reaching ‘a high water mark of active local and popular support’ in the strikes of 1842, which he suggests have been effectively airbrushed from the narrative of Chartism by some historians. He considers other hitherto neglected aspects of the final phase of the movement such as the Land Plan, commending the subscription lists as an invaluable source for the later history of the movement; the significance of the events of 1848 offering a revisionist view of so-called ‘fiasco’ interpretations; and exploring the movement’s links with socialism and its global impact. One of the most distinctive features of the book is Brown’s facility for drawing apt comparisons with international parallels, for example, he locates the depression that affected Britain after 1837 within ‘a broader crisis within North American and European economies’; notices parallels between tithings in Wales and hunters’ lodges in Canada in 1838-39 and makes comparisons between the Newport rising with the attack on Harper’s Ferry, twenty years later during the anti-slavery campaign in the United States.

Brown’s revised synthesis now constitutes the most up-to-date, detailed and wide-ranging of any overview of the movement produced for the general reader and will be an invaluable aid to students in tertiary and higher education engaging initially with Chartist history in all its complexity. No prior knowledge is assumed and Brown includes lucid explanations of such basic features of the movement as the origins and terms of the People’s Charter. Chartism remains one of the most stimulating and rigorously probed areas of historical enquiry, as enticing now as when I was first introduced to research into the movement under the guidance of the late Professor F.C. Mather many of whose informed, judicious assessments of the movement emerge from Brown’s analysis with continuing plausibility. Indeed, Brown concludes that Chartism was ultimately defeated not only by its own inner weaknesses but also by effective government control with the authorities in 1848 inflicting ‘a most damaging psychological defeat on the most significant, populist, radical movement of the century bankrupting the long tradition of the mass platform’.

John A. Hargreaves

Thursday 28 August 2014

Sex, Work and Politics: Women in Britain, 1780-1945

JUST PUBLISHED

Although it’s only two years since I produced Sex, Work and Politics, writing a second edition has allowed me to extend its chronological limits back to the 1780s and forward to the end of the Second World War in 1945. The original structure of the book remains unaltered though each chapter has been remodelled to take account of this change and of research published since early 2012. In particular, I have made wider use of contemporary newspapers to position women more firmly within their varied milieus. I have also added two new chapters that consider the role played by women after they received the vote in 1918 and 1928 and the place of women in Britain’s imperial project after 1780.

The first chapter considers the relationship between different approaches that have evolved to explain the role of women in history. This is followed by a chapter that looks at the ways in which women were represented in the nineteenth century in terms of the female body, sexuality and the notion of ‘separate spheres‘. Chapter 3 explores the relationship between women and work and how that relationship developed. For working-class women, the critical issue was their increasing economic marginalisation as the result of the masculinisation of work through control over technology, opposition to women’s role in the key sectors of the economy and the identification of certain types of work as specifically ‘female’. For middle-class women caught in the tightening vice of ‘surplus numbers’, the problem was that growing numbers of especially single women needed to find employment to maintain their social position but who often lacked the education necessary to do so. The growing professionalisation of women’s work with the emergence of teaching and nursing and the assault on the male preserve in medicine and the law was the critical development for the middle-classes.

Although women’s suffrage has had a symbolic importance for generations of feminists, the campaign for the vote has obscured the broader agitations for women’s rights during the nineteenth century and was, in terms of its impact before 1914, far less significant. Before the 1880s, the focus was not on winning the vote and the demand for parliamentary suffrage was only one of a range of campaigns. Between 1850 and 1880, a number of significant battles were fought and won. Some of these sought access to the public sphere in education, the professions and central and local government. Others aimed to improve women’s legal and economic status within marriage. Married women’s property rights, divorce, custody of children, domestic violence as well as prostitution were all significant areas in which Victorian middle-class feminists campaigned for changes in the male-oriented status of the law and the differing moral standards to which wives and husbands were expected to conform. This was particular evident in the successful campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts from the mid-1860s and in the growing significance of girls’ schooling and the campaign for higher education, issues are examined in Chapter 4.

The following two chapters look at the ways in which women actively sought access to the public sphere through political activity and demands for suffrage reform. Women’s interest in securing access to political rights was not limited to the campaign for parliamentary suffrage and from the eighteenth century women—proto-feminists--had been challenging the patriarchy. Women, from working- and middle-classes were involved in political protest such as the Chartist movement and in campaigns against slavery and the Corn Laws. The growing powers given to various levels of local government also attracted their keen interest and in the arena of local party politics women were to play a prominent role as early as the 1870s. For some women, suffrage was not the central issue and, those women who supported the Fabian Society were more concerned with improving the economic status of women as a necessary precursor to gaining the vote. Although there had been calls for women’s suffrage from the early nineteenth century and especially after 1832, it was not until the mid-1860s that campaigns outside Parliament sought to influence and pressurise MPs to introduce suffrage reform. There may have been support within both Conservative and Liberal Parties for women’s suffrage but it was not seen as a priority by party leaders and had to rely on individual MPs being willing to introduce bills, all of which were defeated. After thirty years of intermittent campaigning, the suffrage organisations had not achieved any change in the franchise.

It was not until the first decade of the twentieth century that the suffrage movement achieved widespread national recognition largely through the activities of the militant Suffragettes led by the controlling Pankhursts and the non-militant campaigning of the Suffragists. These wings of the suffrage movement agreed about ends but disagreed about some of the means used to achieve those ends: it was a question of deeds or words. The nature of the suffrage campaign is considered in Chapter 7 while reactions to this from anti-suffragists and political parties form the core of Chapter 8. The impact of the First World War on women generally and the suffrage campaign in particular is discussed in Chapter 9. The critical question is whether women gained the vote in 1918 as a reward for their services during the war or whether it was a political imperative that could no longer be reasonably resisted. Chapter 10 considers the role played by women after they gained the vote in 1918 through to the end of the Second World War. Many women emigrated, either on their own or as part of families, to Britain’s growing colonial possessions after 1780. Chapter 11 examines the nature of their role in the development of these colonies. The book ends with an examination of the notion of ‘borderlands’ as a conceptual framework for discussing women in Britain between 1780 and 1945 and the ways in which their personal, ideological, economic, legal and political status developed and changed.

Saturday 24 May 2014

Chartism: Rise and Demise

Just Published

Chartism was the largest working-class political movement in modern British history. Its branches ranged from the Scottish Highlands to northern France and from Dublin to Colchester. Its meetings drew massive crowds: 300,000 at Kersal Moor and perhaps as many as half a million at Hartshead Moor in 1839. The National Petition in 1842 claimed 3.3 million signatures, a third of the adult population of Britain. At its peak, the Northern Star sold around 50,000 copies a week, more than The Times. This was a national mass movement of unprecedented scale and intensity that was more than simply a political campaign but the expression of a new and dynamic form of working-class culture. Across Britain, there were Chartist concerts, amateur dramatics and dances, Chartist schools and cooperatives and Chartist churches that assaulted the political hegemony of the wealthy, the conservative and the liberal. For over a decade, Chartists led a campaign for the franchise with a mass enthusiasm that has never been imitated. Chartism: Rise and Demise provides the analytical narrative for the series. The causes of Chartism and how they have been interpreted is the focus of the opening chapter. The remainder of the book explores the development of Chartism chronologically from its beginnings in the mid-1830s to its demise in the 1850s and divides this into four phases. The first phase covers the years between 1838 and 1841 and revolves round the critical events of 1839, the first Convention, the First Petition and the Newport Rising. The second phase lasts from 1841 to 1843 and focuses on the emergence of the so-called Chartist ‘new move’, the creation of the National Charter Association, the relationship between Chartists and the middle-classes and the strikes of 1842. The third phase covers the years between 1843 and 1850 during which there were attempts to reposition the movement, the Land Plan and the seminal events of 1848. The final phase considers the ways in which the movement developed during the 1850s when leadership moved away from Feargus O’Connor to Ernest Jones.

Friday 9 May 2014

Sir Benjamin Stone 1838-1914

Sir Benjamin Stone 1838-1914: Photographer, Traveller and Politician, 107pp., 20 photographs, ISBN 13: 978-1499265521, ISBN 10: 149926552, £7.99, paperback. Published by the Author under his imprint Birmingham Biographies, this volume is available from Amazon and from other booksellers.

Includes twenty rarely-seen or previously unpublished photographs by Sir Benjamin Stone.

Sir Benjamin Stone lived a full life, and was certainly a more contented man than his restless Birmingham contemporary Joseph Chamberlain. Elected to Parliament in 1895, Stone would have been an undistinguished backbencher had it not been for his camera. On the terrace of the House of Commons he lined up his fellow-MPs and various interesting visitors to have their pictures taken. Dubbed ‘Sir Snapshot’ by the press, he became in these years the most well-known amateur photographer in the country. Stone was an intrepid traveller too, embarking – equipped, of course, with his camera – on a voyage around the world in 1891 and a journey of almost one thousand miles up the Amazon in 1893. He was also an insatiable collector, particularly of botanical and geological specimens and a shrewd businessman, with investments in glass and paper manufacture and house-building and quarrying. Stone was also a Tory politician. He doggedly promoted the Tory cause in Liberal-dominated Birmingham in the 1870s and early 1880s, and, after the Liberal rupture over Irish Home Rule in 1886, became an equally-determined supporter of the new Unionist alliance.

Drawing on newspapers and his own extensive personal papers, this is the first biography of Sir Benjamin Stone to be written. It is published to mark the centenary of his death.

Stephen Roberts is Visiting Research Fellow in Victorian History at Newman University, Birmingham. His published work focuses on Chartism and the political history of Victorian Birmingham.

Wednesday 5 March 2014

Reviewing the Wakefield Court Roll 1812-13

This post is a copy of my review of the excellent Wakefield Court Roll 1812-13 published on The Historical Association website: http://www.history.org.uk/resources/general_resource_7189_73.html

John A. Hargreaves, (editor)

Wakefield Court Roll 1812-13

(Volume XVI, Wakefield Court Rolls Series, Yorkshire Archaeological Society), 2014

262pp., £20 plus £2.75 postage and packing, ISBN 978-1-903564-17-2

Whether 1812 was the worst year in British history, it is certainly up there amongst the worst—1066, 1349, 1914, 1929 and 2008. Britain had been enmeshed in sporadic warfare with France on land and sea since 1793 and its effects were biting hard on Britain’s growing economy. Trade was dislocated, there were widespread bankruptcies, unemployment was growing in part because of technological change and in West Yorkshire this was compounded by the bellicose and destructive activities of the Luddites who sought to reverse the growing tendency of employers to introduce labour-saving machinery to increase their productivity and profits at the expense of the already pressurised workforce.

Halifax in 1834

The publication of the Wakefield Court Roll from 16 October 1812 to 15 October 1813 provides an important insight into the experience of the West Riding in these turbulent times. Manorial court rolls are an important, if neglected, source for the lives and priorities of people and how they coped with changing economic and personal situations. The Wakefield Court Rolls are ‘of outstanding value and importance to the United Kingdom—something recognised by UNESCO—because they survive virtually continuous from 1333 until the manorial courts disappeared in 1925.

Although transcribed medieval and early-modern court rolls are widely published, this volume, for the first time, makes a court roll from the nineteenth century available. John Hargreaves has produced an exemplary edition of what is an extremely important source. His introduction and notes and a detailed index are well-written and an invaluable glossary and map of the Manor of Wakefield make what will be an unfamiliar source for many teachers eminently accessible. What is of particular importance for the classroom is the evidence in the rolls for the Luddite movement—it appears that the Luddite attack on the mill of Joseph Foster in April 1812 did not have a marked impact on his business—and its insight into the legal position of women and their financial and economic autonomy, something often missing from discussions of their role in this period.

This is a volume that deserves a wide audience and has a resonance that extends far beyond the West Riding. I thoroughly recommend it.

Volume 16 of the Wakefield Court Rolls series can be obtained from the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Claremont, 23 Clarendon Road, Leeds, LS2 9NZ, for £20 plus £2.75 postage and packing. Cheques should be made payable to Yorkshire Archaeological Society or you can buy the book on the website by using the link provided.

Friday 28 February 2014

Wakefield Court Rolls

Dr John Hargreaves has produced an excellent edition of the Wakefield Court Roll from 19 October 1812 to 15 October 1813. Volume 16 of the Wakefield Court Rolls series can be obtained from the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Claremont, 23 Clarendon Road, Leeds, LS2 9NZ, for £20 plus £2.75 postage and packing. Cheques should be made payable to Yorkshire Archaeological Society or you can buy the book on the website by using the link provided.

Tuesday 25 February 2014

Reviewing the nineteenth century

I am most grateful to Stephen Roberts for writing a review of these two books. They are printed on his excellent Chartism & The Chartists website: http://www.thepeoplescharter.co.uk/index.htm

Richard Brown, Coping with Change: British Society 1780-1914 (Authoring History, 2013); and Before Chartism: Exclusion and Resistance (Authoring History, 2014).

Those who study, write and teach about Chartism will be familiar with the name of Richard Brown. His Chartism (1998) is one of a clutch of short histories of the movement; but, alongside that by Edward Royle, is the book that would top anyone's recommendations of where to begin when starting out on a study of the Chartists. Brown's contribution to our understanding of Chartism would be useful enough if he had written only that one book ... but he hasn't. Brown is in fact a prodigious writer. He does not, as a rule, delve deeply into primary sources in his writing. What Brown does is immerse himself in the relevant secondary sources; and 'immerse' is the correct verb because the range of Brown's reading takes in almost everything written on a subject and is truly astonishing.

Coping with Change is a door-stopper of a book. At 746 pages, it leaves no gaps - there are chapters devoted to industry, agriculture, transport, public health, education, crime, leisure, religion and so on. All that Brown has to say is thoroughly footnoted, ensuring the reader does not have to check library catalogues for further reading. Brown writes both authoritatively and clearly. With a detailed index, this is an easy book to use. I can pay it no greater tribute than by saying that I shall keep my copy within easy reach of my desk when I am writing.

Before Chartism offers a comprehensive examination of the radical movements and protests that came before the late 1830s. Chartism cannot be understood without knowing what immediately preceded it - the popular unrest that followed the end of the French wars in 1815, the great 'betrayal' of the 1832 Reform Act, the hated Poor Law of 1834, the agitation over the press in 1830s London and so on. I always thought that the introductory chapters of J.T. Ward's Chartism (1973) were useful, if not particularly sympathetic to the leaders of the people. But that book is long out-of-print and the reader seeking up-to-date and reflective writing on these themes needs to consult a range of different books. That is no longer the case. Brown provides, in a well-researched, sympathetic and readable volume, the stories of the campaigns that fed into Chartism. It is another valuable volume from the Brown writing factory.

Tuesday 11 February 2014

Forty years on…

As Christopher Daniels reminded me in his recent article on historical sources, it’s forty years since we wrote out first article on history education. Not only does that means that we’re both growing disgracefully older but that, in the interim, little has changed in the ways that examination boards approach the evaluation of sources. Particularly, and this is the core of Chris’ paper, visual sources are still largely ignored when assessing students. In fact, perusing some old examination papers and comparing them with today’s equivalent, the types of sources used has barely changed at all. What visual material there is is generally in black-and-white rather than colour, the norm in say Geography papers.

http://www.johncatt.com/downloads/pdf/magazines/ccr/ccr51_1/

Saturday 8 February 2014

Dr J. A. Langford (1823-1903): A Self-Taught Working Man and the Sale of American Degrees in Victorian Britain

In the next few weeks, I will be publishing under my imprint Authoring History a short pamphlet on John Alfred Langford (1823-1903) written by Stephen Roberts. This is my first venture into publishing another author’s work and it is a pleasure to take what is well-researched and written and original material into print.

Langford was a man much like Thomas Cooper--whom he knew well. He was an autodidact and the author of much poetry. He also wrote a lot of local history, notably the compendiums A Century of Birmingham Life and Modern Birmingham (1868-73) that are still regularly consulted by local historians. Unlike Cooper, Langford did not get involved in Chartism but worked closely with middle-class radicals like George Dawson in promoting Birmingham's famous ‘Civic Gospel’. Most interestingly, he acquired a doctorate from a little-known American college--a little digging has discovered that this particular institution was selling degrees in mid-Victorian Britain--more than 50 men acquired them according to his research and there was much controversy in the newspapers.

Tuesday 14 January 2014

Suger: The Life of Louis VI 'the Fat'

JUST PUBLISHED

The kingdom of France when Louis VI came to the throne in 1108 was a patchwork of feudal principalities over which the authority of the French Capetian monarchy was weak. Beyond the heartlands of Capetian power around Paris, kings of France had little power and the rulers of the great principalities such as Aquitaine paid little heed to the authority of the French state. Under Louis VI, this gradually began to change and, although it took a further two centuries to complete the process, the feudal supremacy of the French monarchy began to be asserted and the lands over which it had feudal hegemony began to expand. Much of what we know about Louis' reign comes from his life written by his friend and advisor Suger Abbot of St-Denis. Suger was a talented individual who straddled the often perilous divide between Church and State with considerable skill. He was a diplomat, administrator in both ecclesiastical and political spheres and staunch defender of his monastery. He witnessed many of the important events of Louis' reign and knew many of the people he wrote about. His Life of Louis VI is a partial biography, like most medieval biographies, that aims through recounting Louis' life to demonstrate what the nature of 'good' kingship should be--to defend the weak, to dispense justice, to defend both Church and State from those who sought control over them and to defend France against attack from within and without. His is an epic tale of good versus evil, justice versus injustice and right against wrong.

This volume provides a translation of Suger's work with detailed annotation that identify the key participants and explain the significance of the key events. The introduction provides a brief biography of Suger and examines what his intentions were in writing his book. Two appendices look at the French defeat at the Battle of the Two Kings at Brémule in 1119 and the murder of Charles of Flanders in 1127 through the eyes of other medieval writers. There is also a detailed bibliography.

Monday 30 December 2013

Before Chartism: Exclusion and Resistance

AVAILABLE FROM 1ST JANUARY 2014

'An accessible and illuminating study based on an impressive range of reading and with footnotes which in effect provide a critical bibliographical guide to the most relevant... sources, which enhances the utility of the book for students at all levels seeking to engage with the vast literature on Chartism and its antecedents which shows not signs of diminishing. The book is well structured and clearly signposted by headings and sub-headings which are always fresh and entirely fit for purpose, e.g. ‘politics of the Excluded’, ‘Rebellions of the Belly’ etc. The index entries are clearly differentiated. Bibliographical references are invariably balanced and informative, for example, the balanced references to the sources for the life of Robert Peel. Hitherto neglected texts are utilised such as R.I. Moore’s Sir Charles Wood’s Indian Policy which reinforces Brown’s facility for discussing themes in a broad global context...It is also refreshing to see such a strong emphasis on regional and local studies in a work of synthesis of this kind...' Dr John A Hargreaves

Chartism was the largest working-class political movement in modern British history. Its branches ranged from the Scottish Highlands to northern France and from Dublin to Colchester. Its meetings drew massive crowds: 300,000 at Kersal Moor and perhaps as many as half a million at Hartshead Moor in 1839. The National Petition in 1842 claimed 3.3 million signatures, a third of the adult population of Britain. At its peak, the Northern Star sold around 50,000 copies a week, more than The Times. This was a national mass movement of unprecedented scale and intensity that was more than simply a political campaign but the expression of a new and dynamic form of working-class culture. Across Britain, there were Chartist concerts, amateur dramatics and dances, Chartist schools and cooperatives and Chartist churches that assaulted the political hegemony of the wealthy, the conservative and the liberal. For over a decade, Chartists led a campaign for the franchise with a mass enthusiasm that has never been imitated.

Before Chartism: Exclusion and Resistance acts as a preamble to the four volumes in the Reconsidering Chartism series and seeks to summarise current thinking. The prologue examines the nature of economic networks in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century. The first chapter explores the ways in which society changed in the decades leading up to the beginnings of Chartism and confronts the central issue of how far society was a class-based. Chapter 2 considers the radical legacy from the 1790s to the collapse of the Whig government in 1841 and surveys key questions such as the ways in which working people responded to economic change. Chapter 3 looks at the ways in which working- and middle-class radicals confronting the question of reform from the 1790s through to 1830. The importance of the radical press and the ‘war of the unstamped’ is explored in Chapter 4. The politics of inclusion and exclusion and the role of repression by the Whig governments in the 1830s is examined in Chapter 5 while the dilemma faced by radicals provides a short conclusion to the book.

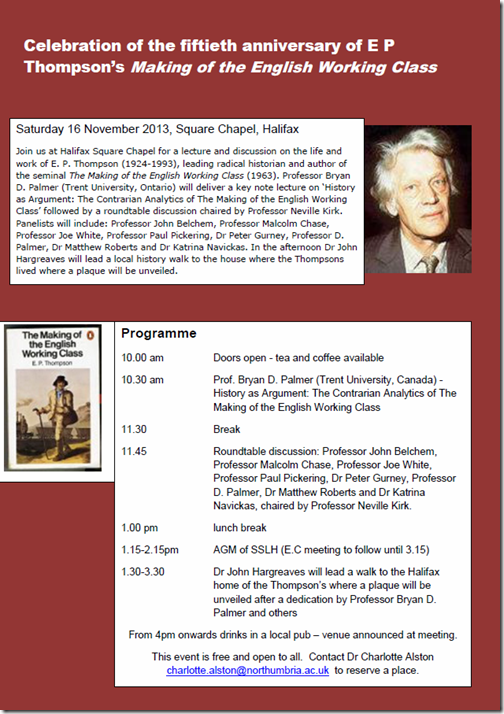

Monday 28 October 2013

Blue plaque for E. P. Thompson

It’s been half a century since Edward Thompson’s seminal study The Making of the English Working Class was published. I first read the book not long after it was published…my father who occasionally bought me books purchased a copy that I still have. I read it quite quickly and was struck by three things: how little of the theory behind the book I understood; its monumental scale and particularly its style and use of language. It is a literary as well as a historical masterpiece whether you agree with Thompson or not. It is appropriate I think twenty years after his death and fifty years after Making was published that a blue plaque will be unveiled on 16 November on the house where he and Dorothy lived in Halifax and where he wrote Making. Dr John A. Hargreaves, the doyen of Halifax historians, is currently preparing a free booklet and guided history trail to mark E.P. Thompson's association with Halifax.