The English were suspicious of any notion of a powerful police that they equated with the Catholic absolutism of France. [1] Louis XIV had established a Royal Police in 1667 under with explicit aim of strengthening royal authority in all fields of life. Public Prosecutors were the King’s agents. By contrast, in England the landowning aristocracy had checked the growth of centralised royal power and the organisation of justice reflected the local power of the landowner as much as that of the monarch. This led to the development of decentralised model of policing in the eighteenth century where the administration of justice and the policing was under local control. For the people, law and crime were rooted in everyday life and community rather than in systems where police and judges represented more distant royal power.

England was unique in having the victim as the initiator of criminal prosecutions and this only declined well into the nineteenth century. It was the victim, not state officials, who initiated investigation and prosecution. In this traditional system of localised, highly personalised justice the main instrument was the court and the trial. Crime detection and policing methods were elementary and crude. Courts waited for matters to be brought before them. This was a system of personal power in which landowners put in a good word for their labourers, something that helped consolidate their personal standing and power in the community. This was not an abstract system of justice but one where justice was perceived in terms of personal relationships and where justice was tempered with mercy.

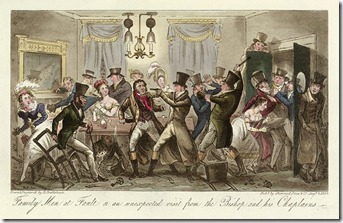

In the late-eighteenth century, however, this informal, personal system began to break down before the increasing incidence of urban unrest and property crime, especially in London.[2] For the urban middle-classes, rising crime was a symptom of the need for new forms of control of the lower orders. The notion of the ‘rule of law’, an impartial application of the law between different social groups gained ground and displaced the older rural notion of deferential justice. This reflected the changing nature of urban capitalist society in which the relationship between the offender and the victim became more impersonal as the face-to-face society irretrievably broke down. Crime was no longer seen as simply a wrong, a personal interaction between individuals or individuals and their superiors, it became a disruption, in which an offence against the criminal law was a disruption of the public peace and of the effective working of society. This led to a shift from the centrality of the court that had no implications for the working of society to an emphasis on police and crime detection to minimise disruption to the working of society.

Fears of a continental style of a state-controlled national police force remained and greatly increased during the Napoleonic Wars, when reported excesses of the militaristic gendarmerie were prominently reported in British newspapers and journals. Although this traditional fear was anathema to the English gentry and their notion of liberty, the urban middle-classes had a very different view of the problem of security.

The squirearchy might treasure the discretion which the old system allowed them, to choose among a variety of punishments ranging from an informal reprimand to death; but the urban shopkeeper wanted something which would efficiently protect his commercial property.[3]

The ruling classes increasingly feared the anarchy of the city and a war of all against all, a fear that reached its peak in the 1790s when they viewed events in France. This fear was a diffuse concern with political disorder, lack of the correct habits of restraint and obedience and criminality that merged into one another in a general fear of disorder. This was later eloquently expressed in the Tory Blackwood’s Magazine that warned

...the restraints of character, relationship and vicinity are... lost in the crowd...Multitudes remove responsibility without weakening passion.[4]

Police reformers, such as John Fielding and Patrick Colquhoun and the commercial and propertied middle-classes increasingly advocated rigorous control and surveillance of the lower classes by a more systematically organised and coordinated police force.[5] Such proposals were vehemently opposed by the gentry and the emerging industrial working-class that feared that the government would form a powerful, centralised police force to ride roughshod over their liberties. With the crucial support of Tory backbenchers, they resisted efforts to establish French-style police methods in England. The most important development was the Middlesex Justices Act of 1792 that appointed stipendiary or paid magistrates in charge of small police forces. But the predominantly local system of policing was still in place in the 1820s.

Sir Robert Peel was responsible for introducing two approaches of policing in Britain. First, when Secretary of State for Ireland between 1812 and 1818, he established the Peace Preservation Force in 1814 and later the Irish Constabulary Act of 1822 established police forces in county areas and created a more militarised and centralised form of policing.[6] This body was a paramilitary police force whose aim was less the detection and prevention of crime than the wider political task of subduing the Catholic Irish peasantry. There was less resistance to stern measures against agrarian protest and violence in Ireland. Secondly, Peel, when Home Secretary after 1822, used arguments based on the efficiency of the Irish police and the threat to liberty from disorder and crime to achieve police reform in England. Peel pushed the Metropolitan Police Act through Parliament in 1829 creating a paid, uniformed, preventive police for London headed by commissioners without magisterial duties and under central direction. The example of uniformed, professional police subsequently spread throughout England over the following decades, but they remained under local control and the extent to which the new police differed from the existing watchmen and constables should not be exaggerated.[7] These developments provided two different models for policing. First, a centralised, military styled and armed force of Ireland kept away from the local community in barracks. Secondly, a consciously non-military, unarmed, preventive English police supposedly working in partnership with and with the consent of the local community.[8] More often than not elements from both models were employed by colonial police forces and adapted to suit local circumstances. Where the security of the state was threatened, the Irish approach was deployed, while English methods were more pervasive and influenced day-to-day policing of all aspects of social life.

During the 1950s and 1960s, historians of English policing argued that the introduction of the ‘new police’ received widespread community support. The few individuals, who opposed its introduction, it was argued, were soon won over by the force’s ability to prevent crime and maintain social order, so securing it ‘the confidence and the lasting admiration of the British people’.[9] The smooth transition from a locally based ‘inefficient’ parish constable system to an efficient and professional body of law enforcers formed the basis of this ‘consensus’ view. During the 1970s, historians using conflict and social control theories challenged the consensus view of widespread public acceptance. Concentrating on working-class responses, they argued that the ‘new police’ were resisted as an instrument of repression developed by the propertied classes. The ‘new police’ were developed to destroy existing working-class culture and impose ‘alien values and an increasingly alien law’ on the urban poor’.[10] Conflict historians argued that a preventive police system was developed in response to changes in the social and economic structure of English society. Robert Storch, its foremost proponent contended that, the formation ‘of the new police was a symptom of both a profound social change and deep rupture in class relations’.[11] The working-class, it was argued, questioned the legitimacy of the ‘new police’ and responded to their interference in a variety of ways ranging from subtle defiance to open and, on occasions, violent resistance.

More recently the level of support that the ‘new police’ received from the propertied classes has been questioned. Barbara Weinberger argues that opposition to the ‘new police’

...was part of a ‘rejectionist’ front ranging from Tory gentry to working class radicals against an increasing number of government measures seeking to regulate and control more and more aspects of productive and social life.[12]

Stanley Palmer also argues that conflict historians ‘have tended to ignore or down play the resistance within the elite to the establishment of a powerful police’ and have over-emphasised the threat from below.[13] While accepting that the introduction of the ‘new police’ involved a clash of moral standards, Palmer argues that it should not be exaggerated.[14] These more recent studies therefore suggest that opposition to the ‘new police’ was also, but not equally, a response of the English upper- and middle-classes.

The broad generalisations regarding public opposition or acceptance of the ‘new police’ have tended to obscure the subtleties in community responses. Opposition did exist, at times resulting from police enforcement of ‘unpopular edicts’ or attempts to ‘prevent mass meetings,’ although they were also used and supported by many people ‘as a fact of life’ in their preventive and social order capacities.[15] While these studies have concentrated predominantly on the public’s negative responses to the introduction of the ‘new police’, Stephen Inwood has considered how the police, administratively and functionally, dealt with the public. Too great a reliance on social control theories, Inwood argues, has led to over-simplification of the complex inter-relationships between the ‘new police’ and the wider community. While the ‘new police’ sought ‘to establish minimum standards of public order,’ it was not in their own interests ‘to provoke social conflict by aspiring to unattainable ideals’.[16] Inwood sees relations between the police and the public as based on a calculated pragmatism in which it was acknowledged that attempts to impose unpopular laws rigidly would ultimately meet with resistance resulting in ‘damage to the rule of law’.[17] Police administrators and the constables were required to tread carefully between the demands and expectations of ‘respectable’ society and the practical need for good relations with the working-class.[18] While there has been a re-examination of public responses to the ‘new police’ and police responses to the public, these studies maintain that the police were, amongst particular groups, for varying reasons and at certain times, unpopular. Weinberger argues that this unpopularity stemmed from public

...suspicion of the police as an alien force outside the control of the community; resentment at police interference in attempting to regulate traditionally sanctioned behaviour; [and] objections to expense.[19]

[1] Lenman, Bruce and Parker, Geoffrey, ‘The State, The Community and Criminal Law in Early Modern Europe’, in Gatrell, V. A. C., Lenman, Bruce and Parker, Geoffrey, (eds.), Crime and the Law: The Social History of Crime in Western Europe Since 1500, (Europa), 1980, pp. 11-48.

[2] Philips, David, ‘‘A New Engine of Power and Authority’: The Institutionalization of Law-Enforcement in England, 1780-1830’, in ibid, Gatrell, V. A. C., Lenman, Bruce and Parker, Geoffrey, (eds.), Crime and the Law: The Social History of Crime in Western Europe Since 1500, pp. 155-189; Hay, Douglas and Snyder, Francis, (eds.), Policing and Prosecution in Britain, 1750-1850, (Clarendon Press), 1989; Emsley, Clive, The English Police: A Political and Social History, 2nd ed., (Longman), 1996, pp. 15-23; McMullan, J. L., ‘The Arresting Eye: Discourse, Surveillance, and Disciplinary Administration in Early English Police Thinking’, Social and Legal Studies, Vol. 7, (1998), pp. 97-128. Gattrell, V., ‘Crime, authority and the policeman-state‘, in ibid, Thompson, F.M.L., (ed.), The Cambridge Social History of Britain 1750-1950: Vol. 3 Social Agencies and Institutions, pp. 243-310 provides a good overview.

[3] Philips, D., ‘‘A New Engine of Power and Authority’ The Institutionalisation of Law Enforcement in England 1750-1830’, in ibid, Gatrell, V. A. C., Lenman, Bruce and Parker, Geoffrey, (eds.), Crime and the Law, p. 126.

[4] ‘Causes of the Increase in Crime’, Blackwood’s Magazine, Vol. 56 (July 1844), p. 8.

[5] See, for example, Colquhoun, P., A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis, (H. Fry), 1796.

[6] Palmer, S. H., Police and Protest in England and Ireland, 1780-1850, (Cambridge University Press), 1988, chapters 6 and 7.

[7] Styles, John, ‘The Emergence of the Police: Explaining Police Reform in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century England’, British Journal of Criminology, Vol. 27 (1987), pp. 15-22.

[8] Brogden, Michael, ‘An Act to Colonise the Internal Lands of the Island: Empire and the Origins of the Professional Police’, International Journal of the Sociology of Law, Vol. 15, (1987), pp. 179-208; Anderson, D.M. and Killingray, David, (eds.), Policing and the Empire: Government, Authority, and Control, 1830-1940, (Manchester University Press), 1991.

[9] Jones, David, ‘The New Police, Crime and People in England and Wales, 1829-1888,’ Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 33, (1983), p. 153. For discussions of this debate see, ibid, Emsley, Clive, Policing and its Context, 1750-1870, pp. 4-7; Bailey, V., ‘Introduction’, in ibid, Bailey, V., (ed.), Policing and Punishment in Nineteenth Century Britain, pp. 12-14; Fyfe, N.R., ‘The Police, Space and Society: The Geography of Policing’, Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 15, (3), (1991), pp. 250-252; ibid, Brogden, M., ‘An Act to Colonise the Internal Lands of the Island: Empire and the Origins of the Professional Police’, pp. 181-183.

[10] Ibid, Jones, David, ‘The New Police, Crime and People in England and Wales, 1829-1888’, p. 153.

[11] Storch, R., ‘The Plague of the Blue Lotus: Police Reform and Popular Resistance in Northern England, 1840-57’, International Review of Social History, Vol. 20, (1975), p. 62.

[12] Weinberger, B., ‘The Police and the Public in Mid-nineteenth-century Warwickshire’, in ibid, Bailey, V., (ed.), Policing and Punishment in Nineteenth Century Britain, p. 66.

[13] Ibid, Storch R., ‘The Plague of the Blue Lotus: Police Reform and Popular Resistance in Northern England, 1840-57’, p. 61; ibid, Palmer S. Police and Protest in England and Ireland, 1780-1850, p. 8.

[14] Storch, R., ‘Policeman as Domestic Missionary: Urban Discipline and Popular Culture in Northern England, 1850-1880’, Journal of Social History, Vol. 9, (4), (1976), pp. 481-509.

[15] Ibid, Jones, David, ‘The New Police, Crime and People in England and Wales, 1829-1888’, p. 166; Ibid, Emsley, Clive, The English Police, pp. 5-6.

[16] Inwood, S., ‘Policing London’s Morals: The Metropolitan Police and Popular Culture, 1829-1850’, London Journal, Vol. 15, (2), (1990), p. 144.

[17] Ibid, Inwood, S., ‘Policing London’s Morals: The Metropolitan Police and Popular Culture, 1829-1850’, p. 134.

[18] Ibid, Inwood, S., ‘Policing London’s Morals: The Metropolitan Police and Popular Culture, 1829-1850’, p. 131

[19] Ibid, Weinberger, B., ‘The Police and the Public in Mid-nineteenth-century Warwickshire’, p. 65.