Today we are concerned about ‘organised crime’. In the nineteenth century, contemporaries debated the existence of professional criminals and the more ambiguous ‘criminal classes’, a notion given credence by the collection and publication of statistics. The Report of the Royal Commission on the Rural Constabulary 1839, largely drafted by Edwin Chadwick, attempted to explain crime across England and Wales.[1] Criminality was rooted in the poorer classes, especially those who roamed the country: ‘the prevalent cause of vagrancy was the impatience of steady labour’.[2] Chadwick and his fellow commissioners were either unaware of, or simply ignored the seasonal nature of much nineteenth century employment and the need of many, even urban dwellers, to spend time moving from place to place and from job to job. Poverty and indigence did not lead to crime, the Report insisted. Criminals suffered from two vices: ‘Indolence or the pursuit of easy excitement’.[3] They were drawn to commit crimes by ‘the temptation of the profit of a career of depredation, as compared with the profits of honest and even well paid industry’.[4] For Chadwick, criminals made a rational decision to live by crime because of its attractions.

Chadwick and other reformers identified a criminal group within the working-class that possessed the worst habits of the class as a whole. [5] The issue was one of ‘bad’ habits and vices that were then identified as the causes of crime. The 1834 Select Committee enquiring into drunkenness concluded that the ‘vice’ was declining among the middle- and upper-classes but increasing among the labouring classes with a notable impact on crime.[6]

Employment and good wages led to greater consumption of alcohol that, on occasions, contributed to a greater incidence of violent behaviour. The problem, the Committee concluded, was the poor‘s lack of morality. ‘Lack of moral training’ was not a new issue in 1834, but it was taken up and emphasised by several educational reformers in the next two decades especially as concern grew about juvenile delinquency. Individuals such as Mary Carpenter, John Wade and James Kay-Shuttleworth argued that proper education would lead to a reduction of crime but that it was not secular education merely involving reading, writing and arithmetic that they wanted. Jelinger Symons explained that

When the heart is depraved, and the tendencies of the child or the man are unusually vicious, there can be little doubt that instruction per se, so far from preventing crime, is accessory to it. [7]

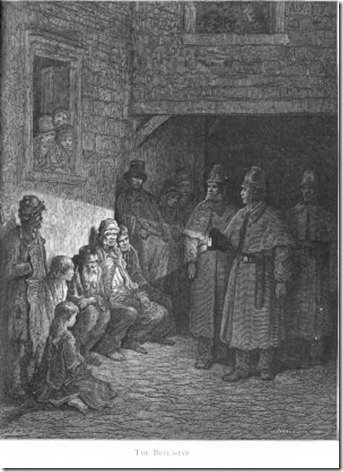

Gustav Doré published in 1872 in the book London, with a text by Blanchard Jerrold

What was needed was Christian and moral education that would explain to the working classes their true station in life. This education had to instil in the young habits of industry. If bad parents or the efforts of ragged schools or Sunday Schools failed to do this, then reformatory schools would have to take over. Jelinger Symons again

There must be a change of habit as well as of mind, and the change of habit mostly needed is from some kind of idleness to some kind of industry. We are dealing with a class whose vocation is labour; and whose vices and virtues are infallibly connected with indolence and industry.[8]

The economic and political instability of the 1830s and especially the 1840s saw people at opposite ends of the political spectrum share increasingly ominous visions of society. Friedrich Engels wrote that

...the incidence of crime has increased with the growth of the working-class population and there is more crime in Britain than in any other country in the world.[9]

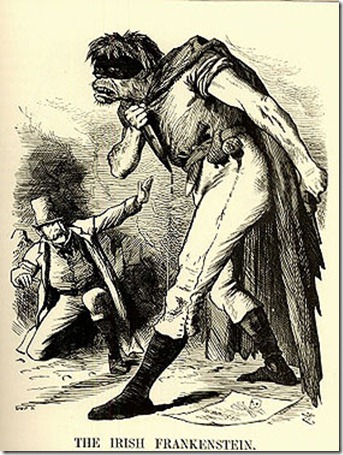

Crime was an aspect of the new social war that worsened with every passing year. In the mid-1840s, the Chartist G.W.M. Reynolds published the fictional The Mysteries of London that gave his readers a frightening portrait of a brutalised, savage poor, a truly dangerous class.[10] While in Paris, Reynolds had been impressed by Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris and his serial paralleled Sue’s tale of vice, depravity, and squalor in the Parisian slums with a sociological story contrasting the vice and degradation of London working-class life with the luxury and debaucheries of the hedonistic upper crust.[11] The middle-classes in England readily accepted this vision of their social inferiors if nothing else because the poor looked very different in physique as well as dress. [12]

Between the 1850s and the 1870s, a succession of middle-class commentators, as often as not guided by local policemen penetrated the dark and teeming recesses of working class districts. They then wrote up their exploits for the delight of the reading public as journeys into criminal districts where the inhabitants were best compared with Red Indians or varieties of black ‘savages’. Such literature is at its best in the writings of Henry Mayhew, a reporter for the Morning Chronicle, who incorporated his findings in the massive, four volume London Labour and the London Poor: A Cyclopaedia of the Conditions and Earnings of those that will work, those that cannot work and those that will not work between 1851 and 1861-1862. Mayhew noted the different physical and mental characteristics of the nomadic street people

There is a greater development of the animal than of the intellectual and moral nature of man.... They are more or less distinguished for their high cheek-bones and protruding jaws -- for their use of a slang language -- for their lax ideas of property -- for their general improvidence -- their repugnance to continuous labour -- their disregard of female honour -- their love of cruelty -- their pugnacity -- and their utter want of religion.[13]

In short these ‘exotic people’ lacked all of the virtues that respectable middle-class Victorian society held dear. Lurking among these people there was a separate ‘class’ of thieves who were mainly young, idle and vagrant and who enjoyed the literature that glorified pirates and robbers. In the final volume of London Labour, first published in 1861-1862, Mayhew concentrated on ‘the Non-Workers, or in other words, the Dangerous Classes of the Metropolis’. Mayhew himself set out to define crime and the ‘criminal classes’. Crime, he argued, was the breaking of social laws in the same way that sin and vice broke religious and moral laws.[14]

From the middle of the century, many commentators confidently maintained that crime was being checked. There remained, however, an irredeemable, residuum that, with the end of transportation, could no longer be shipped out of the country. This group was increasingly called the criminal class: the backbone of this class was those defined by Mayhew as ‘professional’ and by legislators as ‘habitual’ criminals. The Times commented in a leading article in 1870 that these men

Are more alien from the rest of the community than a hostile army, for they have no idea of joining the ranks of industrious labour either here or elsewhere. The civilised world is simply a carcass on which they prey, and London above all, is to them a place to sack.[15]

In the late 1860s, James Greenwood, a journalist, noted that many juveniles resorted to crime because of hunger, yet in general habitual criminals were rarely perceived as bring brought to crime by poverty.[16] Bad, uncaring parents, drink, the corrupt literature that glamorised offenders and the general lack of moral fibre continued to be wheeled out as the causes of crime. The problem that contemporaries had was to explain the persistence of crime in spite of the advantages and opportunities provided by the advance of civilisation and the expansion of the mid-century panacea of education. The old stand-bys of poor parenting, corrupting literature etc. were combined with the mixing of first-time offenders with habitual offenders in prisons, concepts of hereditary and ideas drawn from the development of medical science.[17]

Early in the century, phrenologists[18] had visited prisons to make case studies of convicts in the belief that inordinate mental faculties led to crime. A visitor to Newgate prison in the 1830s said the prisoners had ‘animal faces’. From 1850, doctors like James Thompson, who worked in Perth prison, began collecting biological analyses of convicts, thus providing an academic veneer to these perceptions of ‘animal propensities’ through empirical research.

The work of Charles Booth in the 1880s and 1890s, with its exposure of bad housing and inadequate diet, encouraged a perception of the residuum as the product of the inevitable workings of social Darwinism. Arnold White, who in the 1900s was the central figure in warning the public about the degeneration of the British race, first expressed his concerns in the 1880s.[19] The fundamental problem was not class but ‘degeneracy’ and hereditary and urban environment were the keys to understanding. Degeneracy was inherited or could be acquired when an individual adopted and deliberately persisted in a life of crime. The problem was made worse by the highly concentrated nature of cities that led to the ‘creation of a large degenerate caste’.[20]

The key elements about the perceptions of the criminal class were, first, that the criminal class was perceived as overwhelmingly male; and secondly, the perceptions were those of middle-class commentators who were speaking to a predominantly, though not exclusively, middle-class and ‘respectable’ audience. There were occasional references to women committing crimes, even to them being afflicted by criminal ‘diseases’, but in general, they were seen as accessories in crime.[21] There was, however, a parallel between perceptions of the male criminal and the female prostitute. Prostitution was not in itself a criminal offence, but there was growing concern about ‘the Great Social Evil’ and from 1850 determined attempts at control. Dr William Acton‘s Prostitution, Considered in its Moral, Social and Sanitary Aspects, in London and Other Large Cities did not see prostitution as the slippery slope of damnation and noted that young women often became prostitutes only for a short while. But there are important parallels between his list of the causes of prostitution and the causes of crime among the criminal and/or dangerous classes

Natural desire. Natural sinfulness. The preferment of indolent ease to labour. Vicious inclinations strengthened and ingrained by early neglect, or evil training, bad associates, and an indecent mode of life. Necessity, imbued by the inability to obtain a living by honest means consequent on a fall from virtue. Extreme poverty. To this blacklist must be added love of drink, love of dress, love of amusement.[22]

Contemporaries across much of Europe and North America, as well at in Britain, were convinced that the crux of the question of what caused crime was the existence of a separate criminal class. This view was reinforced by prevailing social and scientific attitudes and by the publication of sensationalist literature and through factual reporting in the burgeoning popular press. There were individuals and groups who were ‘professional criminals’ and who made a significant part of their living from crime but whether there was a ‘criminal class’ is far more debatable. The use of ‘class’ implies a larger number and a more homogeneous group than actually existed. Contemporaries drew a dubious parallel, grounded in fear and a slanted reading of criminal statistics between offenders who came largely from the working class and the location of the causes of crime within what were generally perceived as the vices of this class.

In fact, there were perhaps no more than 4,000 ‘habitual criminals’ in the 1870s and the scale of the problem was considerably less than the middle-classes believed. Most thefts and most crimes of violence were not the work of professional criminals. Court records suggest that the overwhelming majority of thefts that were reported and prosecuted were opportunist and petty. Most incidents of violence involved people who were either related or who were known to each other. Evidence from the Black Country and London suggests that no clear distinction can be made between a dishonest criminal class and a poor, but honest, working class.[23] The working-classes were more likely to be victims of crime in inner city areas than members of the middle-classes. Despite this, belief in a criminal class persisted and was convenient for insisting that most crime was something committed on law-abiding citizens by an alien and ‘dangerous’ group and, since no reformation was possible, justified the use of draconian punishment.

[1] Philips, David, ‘Three “moral entrepreneurs” and the creation of a “criminal class” in England, c.1790s-1840s’, Crime, Histoire et Sociétés, Vol. 7, (2003), pp. 79-107 considers Colquhoun, Chadwick and Miles. See also, Ekelund, Robert B. and Dorton, Cheryl, ‘Criminal justice institutions as a common pool: the 19th century analysis of Edwin Chadwick’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 50, (3), (2003), pp. 271-294.

[2] First Report of the Commissioners appointed to enquire into the Best Means of Establishing an Efficient Constabulary Force in the Counties of England and Wales, (W. Clowes and Son), 1839, p. 63

[3] Ibid, First Report of the Commissioners appointed to enquire into the Best Means of Establishing an Efficient Constabulary Force in the Counties of England and Wales, p. 64.

[4] Ibid, First Report of the Commissioners appointed to enquire into the Best Means of Establishing an Efficient Constabulary Force in the Counties of England and Wales, p. 128.

[5] The problems involved in defining a ‘criminal class’ are explored in Bailey, V., ‘The fabrication of deviance: ‘dangerous classes’ and ‘criminal classes’ in Victorian England’, in Rule J. and Malcolmson, R., (eds.), Protest and survival: the historical experience; essays for E.P. Thompson, (Merlin Press), 1993, pp. 221-256, McGowen, Randall, ‘Getting to Know the Criminal Class in Nineteenth-Century England,’ Nineteenth-Century Contexts, Vol. 14, (1990), pp. 33-54, Taylor, David, ‘Beyond the bounds of respectable society: The “dangerous classes” in Victorian and Edwardian England’, in Rowbotham, Judith and Stevenson, Kim, (eds.), Criminal conversations : Victorian crimes, social panic, and moral outrage (Ohio State University Press), 2005, pp. 3-22, Wiener, M., Reconstructing the criminal: culture, law and policy, 1830-1914, (Cambridge University Press), 1991 and Men of blood: violence, manliness and criminal justice in Victorian England, (Cambridge University Press), 2004. See also, Carpenter, Mary, Reformatory schools for the children of the perishing and dangerous classes and for juvenile offenders, (C. Gilpin), 1851 and Adshead, Joseph, ‘On juvenile criminals, reformatories, and the means of rendering the perishing and dangerous classes serviceable to the state’, Transactions of the Manchester Statistical Society, (1855-6), pp. 67-122.

[6] Speech by James Silk Buckingham, Evidence on Drunkenness presented to the House of Commons, (Benjamin Bagster), 1834, pp. 2-24.

[7] Symons, Jelinger C., ‘Special Report on Reformatories in Gloucestershire, Shropshire, Worcestershire, Herefordshire and Monmouthshire and in Wales’, printed in the Minutes of the Parliamentary Committee on Education, Parliamentary Papers, 1857-58, p. 236.

[8] Ibid, Symons, Jelinger C., ‘Special Report on Reformatories in Gloucestershire, Shropshire, Worcestershire, Herefordshire and Monmouthshire and in Wales’, p. 238.

[9] Engels, F., The Condition of the Working-class in England, 1844, translated, with foreword by V. Kiernan, (Penguin), 1987, p. 146.

[10] The Mysteries of London, a penny dreadful was begun by Reynolds in 1844 and he the first two series of this long-running narrative of life in mid-nineteenth century London. Thomas Miller wrote the third series and Edward L. Blanchard the fourth series of this immensely popular title. Instalments were published weekly with a single illustration and eight pages of text printed in double columns and later bound together as single volumes. See, Carver, S.J., ‘The wrongs and crimes of the poor: the urban underworld of The Mysteries of London in context’, in Humpherys, Anne and James, Louis, (eds.), G.W.M. Reynolds: nineteenth-century fiction, politics, and the press, (Ashgate), 2008, 149-162.

[11] Les Mystères de Paris, a feulliton or French newspaper serial, was one of the most influential novels of the nineteenth century. While it is little known today, when it first ran as a weekly serial it outsold Alexandre Dumas pere’s The Count of Monte Cristo, and was praised by Victor Hugo, who called its author, Eugène Sue, the ‘Dickens of Paris.’ An English translation was published in three volumes in 1844. See, Maxwell, Richard, ‘G.M. Reynolds, Dickens and the Mysteries of London’, Nineteenth Century Fiction, Vol. 32, (2), (1977), pp. 188-213.

[12] Angelo, Michael, Penny Dreadfuls and Other Victorian Horrors, (Jupiter), 1977, pp. 80-81. See also, Maxwell, Richard, The Mysteries of Paris and London, (University of Virginia Press), 1992, pp. 1-58.

[13] Ibid, Mayhew, Henry, London Labour and the London Poor: The Condition and Earnings of Those that will work, cannot work, and will not work, Vol. I, p. 3. See also, Beier, A.L., ‘Identity, Language, and Resistance in the Making of the Victorian “Criminal Class”: Mayhew’s Convict Revisited’, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 44, (2005), pp. 499-515 and Englander, David, ‘Henry Mayhew and the Criminal Classes of Victorian England: The Case Reopened’, Criminal Justice History, Vol. 17, (2002), pp. 87-108.

[14] See also, Henry Mayhew and Binny, John, The criminal prisons of London, and scenes of prison life, (Griffin, Bohn, and Co.), 1862, Englander, David, ‘Henry Mayhew and the Criminal Classes of Victorian England: The Case Reopened’, Criminal Justice History, Vol. 17, (2002), pp. 87-108 and Beier, A.L., ‘Identity, Language, and Resistance in the Making of the Victorian “Criminal Class”: Mayhew’s Convict Revisited’, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 44, (2005), pp. 499-515.

[15] The Times 29 March 1870, cit, ibid, Emsley, Clive, Crime and Society in England 1750-1900, p. 73.

[16] See, Greenwood, James, The Seven Curses of London, (Fields, Osgood, & Co.), 1869.

[17] Welshman, John, Underclass: The History of the Excluded, 1880-2000, (Continuum), 2007 examines later developments.

[18] Phrenology developed in the early-nineteenth century. It was based on ‘feeling’ the bumps on a person’s skull. By doing this, phrenologists believed they could draw conclusions about the individual’s personality. See, Stack, David, Queen Victoria’s Skull: George Combe and the Mid-Victorian Minds, (Continuum), 2008, Parssinen, T.M., ‘Popular science and society: the phrenology movement in early Victorian Britain’, Journal of Social History, Vol. 8, (1974), pp. 1-20, Tomlinson, Stephen, ‘Phrenology, education and the politics of human nature: the thought and influence of George Combe’, History of Education, Vol. 26, (1997), pp. 1-22 and Van Wyhe, John, ‘Was Phrenology a Reform Science? Towards a New Generalization for Phrenology’, History of Science, Vol. 42, (2004), pp. 313-331.

[19] See, White, Arnold, The Destitute Alien in Great Britain: A Series of Papers Dealing with the Subject of Foreign Pauper Immigration, (Charles Scribner’s Sons), 1892 and Efficiency and Empire, (Methuen & Co.), 1901.

[20] Morrison, W.D., ‘The Increase in Crime’, The Twentieth Century, Vol. 31, (1892), p. 957, cit, ibid, Emsley, Clive, Crime and Society in England 1750-1900, p. 78.

[21] Zedner, L., Women, Crime and Custody in Victorian England, (Oxford University Press), 1991, pp. 51-92.

[22] Acton, William, Prostitution, (Chirchill), 1857, rep., (Praeger), 1969, p. 118.

[23] Philip, D., Crime and Authority in Victorian England: The Black Country 1835-60, (Croom Helm), 1977, pp. 13-21, 126-129, 287-288.