Conversation with Mr. Quiblier, Father Superior of the Seminary at Montreal, 24 August 1831

Mr. Quiblier struck us as a good-hearted and enlightened cleric. He is a Frenchman who came from France a few years ago.

He. - I do not think there are a happier people in the world than the Canadians. They have very gentle manners, neither civil nor religious dissensions, and they pay no taxes.

Q. But isn’t there here something that remains of the feudal system?

A. Yes, but it is rather a name than anything else. The greater part of Canada is still divided into seigneuries. Those who inhabit or buy a land on these seigneuries must pay a rent to the seigneur as well as droit de mutation.[1] But the rent is really nothing. The seigneur has no honorific privilege, no superiority whatsoever on his censitaire. I think he has a less elevated position than the European owner over his tenants.

Q. How are religious needs covered for?

A. By the tithe. The clergy in general has no landed property. What we call the tithe is 1/26 part of the harvest. It is paid without anger or suffering.

Q. Do you have convents for men?

A. No. In Canada we only have convents for girls. And again the religious women live quite the active life, raising children or caring for the sick.

Q. Do you have freedom of the press?

A. A complete and limitless freedom.[2]

Q. Did the press use its power to turn the people against religion?

A. Never. Religion is too respected for a journalist to attack it in any way.

Q. Are the upper classes of society religious?

A. Yes, very.

Q. Is there animosity between the two races?

A. Yes, but not much. It does not extend to normal social contacts. The Canadians claim that the English government only offers places to the English while the English complain that it favours the Canadians. I think there is exaggeration on both sides of the argument. In general there is little religious animosity between the two peoples, legal tolerance being complete.

Q. Do you think this colony will soon become free from England?

A. I do not think so. The Canadians are happy under the current regime. They have a political liberty almost as great as that enjoyed in the United States. If they were to become independent, there is a multitude of public expenses that would fall onto them; if they were to unite with the United States, they would fear that their population would soon be absorbed in a deluge of emigration and that their ports, closed during four months of the year, would be reduced to nothing if they were deprived of access to the English market.

Q. Is it true that schooling is spreading?

A. In the past few years a complete change has occurred in this regard. It is regarded as a priority and the Canadian race that is now being brought up will not resemble that which exists now.

Q. Do you not fear that these innovations will undermine the religious principle?

A. One cannot yet know the effect it will produce. I nevertheless believe that religion has nothing to worry about.

Q. Is the Canadian race expanding?

A. Yes. But slowly and little by little. It does not have this adventurous spirit or this scorn for birth and family ties that characterise the Americans. The Canadian goes as far as the extremity of his church’s bell and will settle as close as possible to his parents. However the movement is great, as I was saying, and it will expand further I think with the increase of knowledge.

Conversation with Messrs Mondelet

Messrs Mondelet[3] are lawyers at Montreal. They are intelligent and sensible young men.

Q. What proportion of the population in Canada is French and English?

A. Nine to ten. But almost all wealth and trade are in the hands of the English. They have their families and connections in England and so have opportunities not open to us.

Q. Have you many newspapers in French?

A. Two[4]

Q. How many subscribers do they have compared to the subscribers to English papers?

A. 800 to 1,300.

Q. Are those papers influential?

A. Yes. They have very decided influence, but less than one hears is enjoyed by the papers in France.

Q. What is the position of the clergy? Have you noticed among them the political tendencies which they are alleged to have in Europe?

A. Perhaps one might detect in them a secret tendency to rule or direct, but it amounts to very little. Generally speaking our clergy are conspicuously nationalist. That is partly a result of the situation in which they find themselves. From the time immediately after the Conquest up to our own days, the English government has worked in covert ways to change the religious convictions of the Canadians to make them a body more homogeneous with the English. So the interests of religion came to be opposed to the government and in harmony with those of the people. Hence whenever we have had to struggle with the English, the clergy have been at our head or in our ranks. They have continued to be loved and respected by all.

So far from being opposed to ideas of liberty, they have preached them. All the measures we have taken to promote public education, which have been pretty well forced through against the will of the English government, have been supported by the clergy. In Canada, it is the Protestants who support aristocratic notions. The Catholics have been accused of being demagogues. The political position of our priests is peculiar to Canada to such an extent that the priests who occasionally arrive here from France show a compliance and docility towards authority that we cannot understand.

Q. Are morals chaste in Canada?

A. Very.

Travel to Quebec onboard the steamboat John Molson, 25 August 1831

External appearance: of those parts of America which we have visited so far, Canada has the greatest similarity to Europe and, especially, to France. The banks of the Saint Lawrence are perfectly cultivated and covered with houses and villages in every respect like our own. All traces of the wilderness have disappeared; cultivated fields, church towers, and a population as numerous as in our provinces has replaced it.

The towns, Montreal in particular (we have not yet visited Quebec) bear a striking resemblance to our provincial towns. The basis of the population and the immense majority is everywhere France. But it is easy to see that the French are a conquered people. The rich classes mostly belong to the English race. Although French is the language most often spoken, newspapers, notices and even the shop-signs of French tradesmen are in English. Commercial undertakings are almost all in their hands. They are really the ruling class in Canada.

I doubt if this will long be so. The clergy and a great part of the not rich but enlightened classes is French, and they begin to feel their secondary position acutely. The French newspapers that I have read contain a constant and lively opposition against the English. Up to now having few needs and intellectual interests, and with a very comfortable life, the people have imperfectly glimpsed its position as a conquered nation and have given only feeble support to the enlightened classes. But a few years ago the House of Commons, which is almost all Canadian, has taken measures for a wide extension of education.

There is every sign that the new generation will be different from the present generation and in a few years from now, if the English race is not prodigiously increased by emigration and does not succeed in shutting the French in the area they now occupy, the two peoples will clash against one another. I do not think that they will ever merge or that an indissoluble union can exist between them. I still hope that the French, in spite of their conquest, will one day form a fine empire on their own in the New World, more enlightened perhaps, more moral and happier than their fathers. At the present moment the division of the races singularly favours domination by England.

Conversation with Mr. ... at Quebec (merchant)

Q. Do you have something to fear from the Canadians?

A. No. The lawyers and rich people who belong to the French race hate the English. They offer strident opposition to us in our newspapers and in their Assembly. But it is just words and that’s it. The greater part of the Canadian population does not have political passions and in fact almost all the wealth is in our hands.

Q. But do you not fear that this numerous and compact population today without passion might have some tomorrow?

A. Our number rises everyday, we will soon have nothing to fear on this aspect. The Canadians have even more hatred against the Americans than against us.

Note: In speaking of the Canadians a very visible feeling of hatred and scorn was being painted on the phlegmatic physiognomy of Mr. ...

Quebec, 27 August 1831

The country between Montreal and Quebec seems to be as populous as our fine European provinces. Moreover the river is magnificent. Quebec is on a very picturesque site, surrounded by a rich and fertile countryside. Never in Europe have I seen a livelier picture than that presented by the surroundings of Quebec.

All working population of Quebec is French. One hears only French spoken in the streets. But all the shop signs are in English; there are only two theatres which are English. The inner part of the town is ugly, but has no analogy with American towns. It strikingly resembles the inner part of our provincial towns.

The villages we saw in the surroundings are extraordinarily like our beautiful villages. Only French is spoken there. The population seems happy and well-off. The race is notably more beautiful than in the United States. The race there is strong, and the women do not have that delicate, febrile look that characterises most of the women of America.

The Catholic religion there has none of those accessories which are attached to it in those countries of the South of Europe where its sway is strongest. There are no monasteries for men, the convents for women are directed towards useful purposes and give examples of charity warmly admired by the English themselves. One sees no Madonnas on the roads; no strange and ridiculous ornaments, no ex-votos in the churches. Religion is enlightened, and Catholicism here does not arouse the hatred or the sarcasms of the Protestants. I own for my part that it satisfies my spirit more than the Protestantism of the United States. The parish priest here is indeed the shepherd of his flock: he is not at all an entrepreneur of a religious industry like the greater part of American ministers. One must either deny the usefulness of clergy, or have such as are in Canada.

I went today in a lecture cabinet. Almost all the printed newspapers of Canada are in English. They have about the same nature as of those of London. I did not yet read them. In Quebec City a newspaper called the Gazette, half-English, half-French; and a French newspaper called the Canadien. These newspapers have more or less the character of our French newspapers. I have carefully read some issues: they are vehemently opposed to the government and even to all that is English. The epigraph of the Canadien is: Our Religion, Our Language, Our Laws. It is difficult to be more frank. All that can inflame popular passions against the English are carefully reported by this newspaper. I have seen an article in which it was said that Canada would never be happy until it had an administration that was Canadian by birth, by principle, ideas, prejudice even, and that if Canada became independent of England, it would not remain English. In this same newspaper one could find pieces of French verses that were quite nice. Was reported upon a distribution of prizes where the students had played Athalie, Zaïre, la Mort de César. In general the style of this newspaper is common, mixed with anglicisms and strange expressions. It resembles a lot the newspapers in the Vaud canton in Switzerland. I have not yet seen in Canada a single man of talent, nor read a production proving it. The one who must awaken the French population and lead it against the English is not yet born.[5]

The English and the French merge so little that the latter exclusively keep the name of Canadiens, the others continuing to call themselves English.

Visit of a civil court in Quebec

We came into a large hall divided into tiers crowded with people who seemed altogether French. The British arms were painted in full size on the end of the hall. Beneath them was the judge in robes and bands. The lawyers were ranked in front of him.

When we came into the hall a slander action was in progress. It was a question of fining a man who had called another pendard (gallows-bird) and crasseux (stinker). The lawyer argued in English. Pendard, he said, pronouncing the word with a thoroughly English accent, ‘meant a man who had been hanged.’ ‘No’, the judge solemnly intervened, ‘but who ought to be’. At that, counsel for the defence got up indignantly and argued his case in French: his adversary answered in English. The argument waxed hot on both sides in English, no doubt without their understanding each other perfectly. From time to time the Englishman forced himself to put his argument in French so as to follow his adversary more closely; the other did the same sometimes. The judge, sometimes speaking French, sometimes English, endeavoured to keep order. The crier of the court called for ‘silence’ giving the word alternatively its English and its French pronunciation.

Calm re-established, witnesses were heard. Some kissed the silver Christ on the Bible and swore in French to tell the truth, the others swore the same oath in English and, as Protestants, kissed the other side of the Bible which was undecorated. The customs of Normandy were cited, reliance placed on Denisart[6] and mention was made of the decrees of the Parlement of Paris and statutes of the reign of George III. After that the judge: ‘Granted that the word crasseux implies that a man is without morality, ill-behaved and dishonourable, I order the defendant to pay a fine of ten louis or ten pounds sterling.’

The lawyers I saw there, who are said to be the best in Quebec, gave no evidence of talent either in the substance of their arguments or in their ways of expressing them. They were conspicuously lacking in distinction, speaking French with a middle-class Norman accent. Their style is vulgar and mixed with odd idioms and English phrases. They say that a man is ‘charge’ of ten louis meaning that he is asked to pay ten louis. ‘Entrez dans la boite’, they shouted to a witness, meaning that he should take his place in the witness-box.

There is something odd, incoherent, even burlesque in the whole picture. But at the bottom the impression made was one of sadness. Never have I felt more convinced than when coming out from there, that the greatest and most irremediable ill for a people is to be conquered.

Conversation with John Neilson

John Neilson, member of Parliament in Lower Canada.[7]

Mr. Neilson is a Scot. Born in Canada[8] and related by marriage to Canadians, he speaks French as easily as his own language. Mr. Neilson, although a foreigner, may be regarded as one of the leaders of the Canadians in all their struggles with the English government. Although he is a Protestant, for fifteen years continuously the Canadians have elected him as a member of the House of Assembly. He has been an ardent supporter of all measures favouring the Canadians. He with two others was sent in 1825 to England to plead for redress of grievances. [9] Mr. Neilson has a lively and original turn of mind. The antithesis between his birth and his social position leads sometimes to strange contrasts in his ideas and in his conversation.

Q. What does Canada cost the English government in the current year?

A. Between 200,000 and 250,000 sterling pounds.

Q. Does Canada contribute to it?

A. Nothing. The customs dues are used for the colony. We would fight rather than give up a penny of our money to the English.

Q. But what interest has England got in keeping Canada?

A. The interest that great lords have in keeping great possessions that figure in their title deeds, but cause them great expenses and often involve them in unpleasant lawsuits. But one could not deny that England has an indirect interest in keeping us. In case of war with the United States, the St. Lawrence provides a passage for goods and armies right into the heart of America.

In case of war with the peoples of Northern Europe, Canada would supply the timber for building which she needs. Besides the cost is not as heavy as one supposes. England is bound to rule the sea, not for the glory of it, but for existence. The expenses that she is obliged to incur to maintain that supremacy make the occupation of her colonies much less costly for her than they would be for a country only interested in trade with its colonies.

Q. Do you think the Canadians will soon throw off the English yoke?

A. No, at least unless England forces us to it. Otherwise it is completely against our interest to make ourselves independent. We are still only 600 [000] souls in Lower Canada; if we became independent, we should quickly be absorbed by the United States. Our people would, so to say, be crushed under an irresistible mass of immigrants. We must wait till we are numerous enough to defend our nationality. Then we will become the Canadian people. Left to themselves the people here are increasing as fast as in the United States. At the time of the conquest in 1765 we were only 60,000. [10]

Q. Do you think the French race will ever manage to get free from the English race? (This question was put cautiously in view of the birth of the man to whom I spoke.)

A. No. I think the two races will live and mix in the same and, and that English will remain the language of official business. North America will be English; fortune has decided that. But the French race in Canada will not disappear. The amalgam is not as difficult to make as you think. Here it is above all the clergy who sustain your language. The clergy is the only enlightened and intellectual class that needs to speak French and which speaks it unadulterated.

Q. What is the character of the Canadian peasant?

A. In my view it is an admirable race. The peasant is simple in his tastes, very tender in his family affections, very chaste in morals, very sociable, and polite in his manners; with all that he is very well suited to resist oppression, independent and warlike, and brought up in the spirit of equality. Public opinion has incredible power here. There is no authority in the villages, but public order is better maintained there than in any other place on Earth. If a man commits an offence, people shun him, and he must leave the village. If a theft is committed, the guilty man is not denounced, but he is dishonoured and obliged to flee. There has not been an execution in Canada for ten years. Natural children are something almost unknown in our country districts.

I remember a talk with XX (I have forgotten his name); for two hundred years there had not been a single one; ten years ago an Englishman who came to live there seduced a girl; the scandal was terrible. The Canadian is tenderly attached to the land which saw his birth, to his church tower and to his family. It is that which makes it so difficult to induce him to go and seek his fortune elsewhere. Besides, as I was saying, he is eminently sociable; friendly meetings, divine service together, gatherings at the church door, these are his only pleasures. The Canadian is deeply religious; he pays his tithe without reluctance. Anyone could avoid that by declaring himself a Protestant, but no such case has yet occurred. The clergy here is just one compact body with the people. It shares their views, takes part in their political interests, and fights with them against the powers-that-be. Sprung from the people, it only exists for the people. Here it is accused of being demagogic. I have never heard that that is a complaint made against Catholic priests in Europe. The fact is that they are liberal, enlightened and nonetheless deeply religious and their morals are exemplary. I myself am a proof of their tolerance; a Protestant, I have been elected ten times by Catholics to our House of Commons, and I have never heard it suggested that anyone had ever tried to create the slightest prejudice against me on account of my religion. The French priests who come here from Europe, have the same moral standards as ours, but their political approach is absolutely different.

I told you that our Canadian peasants have a strong social sense. That sense leads them to help one another in all moments of crisis. If one man’s field suffers a disaster, it is usual for the whole community to set to work to put it right. Recently XX’s barn was struck by lightning; five days later it had been rebuilt by the voluntary work of neighbours.

Q. There are still some traces of feudalism here?

A. Yes, but so slight that they are almost unnoticed: (1) The lord receives an almost nominal rent for the land which he originally granted. It may for instance be 6 to 8 francs for 90 acres.[11] (2) Corn must be ground at his mill, but he may not charge more than the maximum fixed by law, which is less than one pays in the United States where there is freedom and competition. (3) There are dues for lods et ventes, that is to say that when feudally held land is sold, the seller must give one twelfth of the purchase price to the lord. That would be rather a heavy burden, were it not that the strongest determination of the people is to remain attached to their land. Those are all the traces of feudalism that remain in Canada. Beyond that the lord has no titular rights and no privileges. There is not and cannot be any nobility. Here, as in the United States, one must work to live. There are no tenants. So the lord is normally a farmer himself. However, no matter how equal the footing on which the lords now stand, there is still some fear and some jealousy in the people’s attitude towards them. It is only by going over to the popular party that a few of them have succeeded in getting elected to the House of Commons. The peasants remember the state of subjection in which they were held under French rule. One word lingers in their memory as a political scarecrow is the taille. They no longer know exactly what the word means, but for them it stands for something not to be tolerated. I am sure they would take up arms if there were an attempt to impose any tax whatever to which that name was given.

Q. What conditions of eligibility are there for entry into your House of Commons?

A. There are none.

Q. Who are qualified as voters in the country districts?

A. Anyone with 41 francs income from land is a voter.

Q. Have you no fear of such a great mass of voters?

A. No. All the people have some property and are religious and order-loving; they make good choices and although they take a great interest in the elections, there are hardly ever disturbances at them. The English tried to introduce their system of corruption, but it ran completely aground against the moral standards and honour of our peasants.

Q. What is the position with regard to primary education?[12]

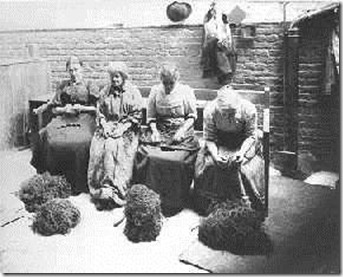

A. It is a long story. In the time of the French there was no education. The Canadian always had a weapon in his hand. He could not spend his time at school. After the conquest the English were only concerned for their own people. Twenty years ago the government wanted to start education, but it took the matter up clumsily. It shocked religious prejudices. It gave the impression that it wanted to gain control of education and to direct it in favour of Protestantism. That at least is what we said, and the scheme foundered. The English said that the Catholic clergy wanted to keep the people in ignorance. Neither side was telling the truth, but that is the way parties speak. Four years ago our House of Commons saw clearly that if the Canadian population did not become educated, it would end up by being entirely absorbed by a foreign population that was growing up by its side and in its midst. Speeches were made, encouragement was given; funds were raised and finally school inspectors were appointed. I am one and I have just completed a tour of duty. Nothing could be more satisfactory than the report which I have to make. The impulse has been given. The people are most active in taking advantage of the chance to get educated. The clergy are all out to help us. We have already got half the children in our schools, about 50,000. In two or three years I am confident we will have them all. Then I hope the Canadian people will begin to leave the river banks and advance towards the interior. At present we stretch about 120 leagues along both sides of the St. Lawrence, but our line is seldom as much as two leagues in depth. However, beyond that there is excellent land that is almost always given away for nothing (that is literally so) and which could easily be cultivated. Labour cost 3 francs in the villages and less in the country. Food is very cheap. The Canadian peasant makes all necessities for himself; he makes his own shoes, his own clothes and all the woollen stuffs in which he is dressed. (I have seen it.)

Q. Do you think French people could come and settle here?

A. Yes. A year ago our House of Commons passed a law to repeal the alien legislation. After seven years’ residence the foreigner becomes a Canadian and enjoys citizen’s rights.

We went with Mr. Neilson to see the village of Lorette three leagues from Quebec, founded by Jesuits. Mr. Neilson showed us the old church built by the Jesuits and told us: ‘The memory of the Jesuits is adored here.’ The houses of the Indians were quite clean. They themselves spoke French and have an almost European appearance despite their costume being different. All were half-breeds. I was surprised not to see them farm the land. Bah! told me Mr. Neilson, these Hurons are gentlemen, they would think it a dishonour to work. Scratching the earth like bulls, they say, that is meant for French or English. They live from hunting and small crafts done by their women.

Q. Is it true the Indians have a fondness for the French?

A. Yes, it is undeniable. The French are perhaps the people who best preserve their original lifestyle and who accept the customs, ideas, and prejudices of those among whom they live. That is by becoming Indians that you obtained from the Indians an affection that still endures.

Q. What has happened to the Hurons who have shown such constant warmth for the French and played such a great role in the history of the colony?

A. They assimilated little by little. They were, however, the greatest Indian nation on this continent. They could arm up to 60,000 men. You see what remains. We think that almost all the Indians of North America have the same origin. There are only the Esquimaux from the Hudson Bay who evidently belong to another race. There, all is different: language, canoes... I was telling you a little earlier of your aptitude to become Indians....

[1] A transfer tax paid on the sale of immoveable property

[2] In late August 1831, at the time of Tocqueville’s visit, it was believed that the days of press censorship and the imprisoning of newspaper owners were over. They, however, returned during the rebellions of 1837-1838.

[3] Dominique Mondelet and Charles-Elzéar Mondelet.

[4] They possibly meant two French-language newspapers in the town of Montreal, or else maybe two daily French-language newspapers in the whole province (La Minerve in Montreal, Le Canadien in Quebec City).

[5] Actually he was. Unfortunately, Louis-Joseph Papineau was staying at his country residence the whole time of Tocqueville’s visit

[6] Denisart Jean-Baptiste, Collection de Decisions nouvelles et de notions relatives a La Jurisprudence Actuelle, six Vols. Paris, 1754-1756 reprinted in seven editions to 1771. This book contained inaccuracies that continuators sought to remove in Collection de décisions nouvelles et de notions relatives à la jurisprudence, donnée par Me Denisart, mise dans un nouvel ordre, corrigée et augmentée published in fourteen volumes from 1783 to 1808.

[7] Pierson, George Wilson, Tocqueville and Beaumont in America, (Oxford University Press), 1938, pp. 328-329 ‘Clearly, Tocqueville and Beaumont did not fully comprehend their guide’s position. Mr. Neilson had been a champion of the French-Canadians since first entering politics. As this very conversation was to show, he entertained a deep affection for the habitants, their simple ways and quaint, antique customs. Furthermore, he wished to see these descendants of the early French colonists develop into a happy, educated, and largely self-governing people; he had always, for example, opposed the Union of Lower Canada with Upper Canada under one Assembly, fearing that this would lead to the destruction of the French-Canadian individuality and to the absorption of the habitants in the English population. On the other hand, Neilson was loyal to England and believed strongly in the Empire tie: according to him the French-Canadians were not yet fit for complete self-government. It followed, therefore, that responsible government was out of the question, and that the Upper House or Legislative Council should remain appointive, rather than be elected by the habitants. One other factor influenced his opinion. Neilson had always believed in reform by constitutional means; and now that he was approaching sixty he was growing distinctly more conservative in his ideas. As a consequence, he was beginning to feel that the nationalist leaders were becoming unreasonable in their demands. Three years later, in 1834, this was to lead to a definite split with Papineau and his followers and to his own defeat for re-election to the Assembly. After investigating American prisons with Dominique Mondelet, therefore, he was to join the Constitutional Association, go to London in 1835 as its representative, and in 1836 make a last effort to prevent the rebellion. On the outbreak of hostilities and the suspension of the government, he was to be appointed a member of the Special Council for the two Provinces. And in 1841, after the Union which he had opposed was finally consummated, he was to be elected as a conservative to the United Legislature.’

[8] John Neilson was born in Scotland in 1776, and emigrated to Canada at the age of 14. He was then joining his older brother Samuel to work at their uncle William Brown’s printing shop in Quebec City. In 1793, he inherited his uncle’s bilingual newspaper La Gazette de Québec/The Quebec Gazette, founded in 1764, the first newspaper in the history of Quebec. See, Chassé, Sonia, Girard-Wallot, Rita and Wallot, Jean-Pierre, ‘John Neilson’, DCB, Vol. 7, 1836-1850, pp. 644-649

[9] John Neilson and Louis-Joseph Papineau were both sent to London to deliver petitions against the Union bill of 1822. In 1828, John Neilson, Denis-Benjamin Viger and Augustin Cuvillier were delegated to London to present petitions against the administration of Governor Dalhousie. Tocqueville is referring to the second event.

[10] The Conquest occurred in 1760 and, after a three-year long military rule of the country, was confirmed in international law with the 1763 Treaty of Paris in which the King of France ceded ‘[...] Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulph and river of St. Lawrence [...]’ to the King of Great Britain.

[11] About 135 English acres.

[12] John Neilson here refers to mass education, specifically, mass literacy which was non-existent under the French regime and most other regimes of the same period. There of course was an education system in the time of New France and it compared favourably to that of many other colonies.