The reform of the Poor Laws extended the growing chasm between the middle-classes and the working population. The poor law, as it existed in the early 1830s was not a system but, in Sidney Checkland’s words, ‘an accretion’, determined by statutes passed two centuries earlier in a different economic and social world without central organisation and left to the discretion and vagaries of local parishes. Any attempt to reconstruct the poor law would have to be both bold and grand. The old poor law, constructed in the late sixteenth century, touched almost every aspect of domestic government.[1] It provided the only general social securities and the only general regulation of labour. But its main characteristic was perhaps the almost compete lack of either central control or uniform policy.[2] The old poor law also provided no clear answers to certain critical questions: was unemployment to be regarded as an offence or a misfortune? Was relief to be administered as a deterrent, as a dole or as a livelihood? Economic distress in the mid-1790s led to the introduction of ‘allowances on aid of wages’, generally though not accurately known as the ‘Speenhamland system’ after its first application in Berkshire in 1795.[3] What was initially perceived as a temporary expedient became a necessity for the labouring population in the depressed agrarian south after 1815. Escalating costs, changing ideological perceptions and the ‘Swing’ riots of 1830 led to an increasingly focused challenge to the existing system that was seen as corrupting, lenient and not cost-effective and for demands that more rigour should be imposed on the poor.[4]

Broadly speaking, opinion on the poor laws was divided into three: those who wished to retain them, those who wished to modify them and those who wished to abolish them. Humanitarians, sentimental radicals and paternalistic Tories belonged to the first group. They believed that there was a strong imperative of humane social responsibility in providing a basic measure of social security for the labouring poor and this seemed to them to outweigh its disadvantages. The second group, who wished to modify the existing system, were to some degree motivated by the same sentiments but were alarmed by its escalating cost and sought to reduce it. The third group was the most influential and powerful if the least numerous. Its guiding lights were political economy and Malthusianism.[5] They believed that labourers must operate within the framework of the free market economy and ‘social discipline’. The latter had the better of the argument and by the early 1830s it had become commonplace among the middle-classes and many of the aristocratic elite, especially the Whigs that the poor laws encouraged indolence and vice. [6]

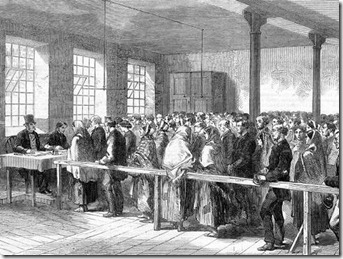

The Royal Commission set up in 1832 to investigate the workings of the poor law was weighted towards ‘progressive’ opinion and quickly confirmed what the Commissioners had set out to prove.[7] There may have been exaggeration of the abuses of the old poor law in the 1834 Poor Law Report. Mark Blaug[8] has shown that its economic consequences were not understood by contemporaries or later historians but there was no confusion about the purpose of those who framed the Poor Law Amendment Act, especially Edwin Chadwick its guiding force. Chadwick could not adopt any of the approaches argued by the three groups. He objected to the basic security conception of the humanitarians and to the notion of the ‘parish in business’. [9]

He, however, differed from the Malthusians and political economists in two important respects. The idea of abandoning any attempt at control was deeply opposed to his bureaucratic temperament. He did not agree with the Malthusian proposition that population must inevitably outrun resources and asserted that there was no economic problem that greater and freer productivity could not solve. His primary objection to the old poor law was that they held down productivity by effectively pauperising the independent labourer and the laws of settlement immobilised a huge labour force that factories were crying out for. Chadwick wanted to ‘de-pauperise’ the able-bodied poor and drive them into the open labour market. This could be achieved, Chadwick believed, through the process of less eligibility because it would be in the labourer’s interest to join the free labour market. This would induce the majority of able-bodied paupers to refuse poor relief and provide capital for development and productivity.

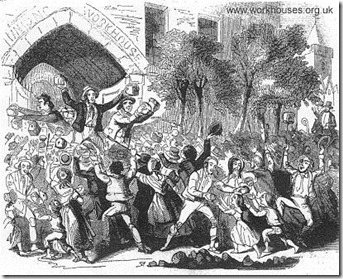

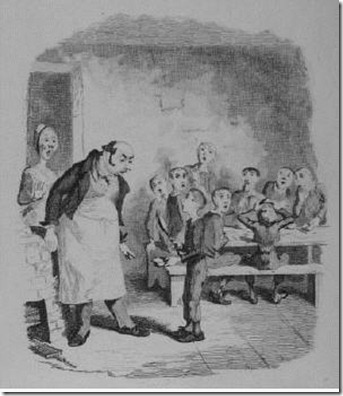

The 1834 Act did not aim to deal with the nature or lack of provision, but only with excess. It had not been politically practical to abolish public relief completely but the relief for those unwilling to unable to make provision for themselves was to be on terms less favourable than those obtained by the lowest paid worker in employment (the principle of ‘less eligibility’). This would eliminate abuse and fraud. Pauperism was a defect of character as there was always work available at the prevailing market price if it was sought strenuously enough. Hard work and thrift would always ensure a level of competence, whatever level individuals were working. These values, reflecting emergent middle-class ideology, made a lasting impression on society for the rest of the century. The sense of shame at the acceptance of public relief, the stigma of the workhouse and the dread of the pauper‘s funeral were central facets of the attitudes of working people. They played a major role in the definition of ‘respectability’ that emerged among both the middle-classes and labourers. The 1834 Act embodied the ideology of the political economists but it could be presented by its opponents as an abuse of the poor: the poor law agitation before 1834 was aimed at amelioration but after 1834 the rigour of the system generated a counter-pressure in favour of easement.[10]

The 1834 Act was important in three respects. First, unlike factory or mine reform, the thinking behind the act was rural rather than urban. This led to the adoption of a programme entirely unsuitable and largely unworkable in the industrial urban setting of northern England and accounted for the widespread opposition to its introduction after 1836.[11] A simple reversal from relaxation to rigour could succeed in the agrarian south to a considerable extent but matters were different in the industrial north. There the new poor law was politicised, first by the anti-poor law agitation and then by the effects of the introduction of the electoral principle into poor law affairs. Secondly, the legislation in 1834 was the result of a generalised view of a whole range of problems and contained a moral rather than an environmental view of the poor and within this framework aimed at internal consistency and comprehensiveness. Finally, it created the first effective element of centralised British bureaucracy, intended to preside over a general social policy with central control and supervision with local administration.

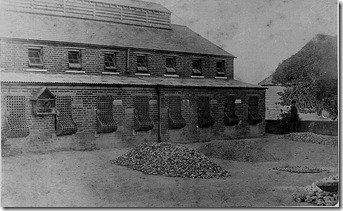

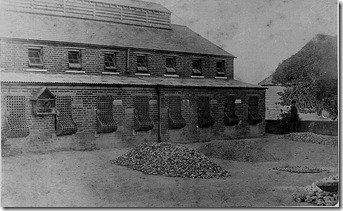

Stoneyard, Elham workhouse, Kent

The standardising intentions of national legislators almost immediately came into conflict with the responses of local people who dealt with the realities of immediate situations. Localities could and did ignore or evade the instructions of the Commissioners. Outdoor relief could not be withheld in seasonal employment like agriculture or during trade depressions in industrial centres. Checkland has argued that

...this generated a kind of schizophrenia when placed alongside the concepts embodied in the governing Act of 1834... [producing] concessions to common sense and common humanity.[12]

Despite this there is no doubt that imposing ‘rigour’ resulted in much hardship under the Act. There are accounts of deficient diet, penal workhouses, families torn apart and the denial of dignity to the old. The poor were abused because of a combination of indifference to their plight and social zealotry because of the dogma enshrined in the enabling legislation.

The Act was intended as an attack on a structural problem: the conditions and behaviour of the labouring poor, especially in agrarian regions, the intention of reducing abuse and to stop confusion between wages and relief. Can this be seen as an expression of middle-class values grounded in the ideology of political economy? In simplistic terms it probably can but the relationship between political economy and poor law policy was in practice far more complex. The uniformity of support for political economy by the middle-classes can be easily over-exaggerated and the nature of the trade cycle resulted in their refusal to implement the full rigour of the 1834 Act in their industrial centres.

The Poor Law Report may have been over-optimistic in believing that uniformity of practice was possible but its principles established attitudes to poverty, which still have current significance. Ursula Henriques maintains that

In 1834 the new development was given a scope, a momentum and a character which made it irreversible. The change was more immediate and more complete in the south than in the north, but it was lasting....The Victorian workhouse and all it stood for....was perhaps the most permanent and binding institution of Victorian England. Not until the working-class had obtained the vote and entirely different attitudes to poverty in general and unemployment in particular began to creep in at the turn of the century did the principles of 1834 start to lose their grip.[13]

Chadwick‘s original proposals were modified in four important respects as the bill went through Parliament during 1834. Each of these changes had more widespread and serious consequences than was anticipated. Chadwick had given his proposed central board powers to forbid absolutely the granting of outdoor relief, the act merely gave permission to ‘regulate’ it. This was vague and clearly opened the way for a retreat towards the old allowance system. He had also given the board the powers of a court of record with the capacity to commit offenders for contempt but this was dropped from the bill during the second reading. This stripped the board of its coercive powers. Chadwick proposed that the board should have powers to compel local guardians of the new unions to raise rates for, and to build new workhouses. The Act limited these coercive powers to a maximum of £50 per year or one-tenth of the annual rate. These sums were inadequate and meant that the central board could not force the local unions into action at all. This concession proved fatal to the system. If the board could not compel the unions to build workhouses, the ‘workhouse test’ failed.[14] Finally, he proposed that the law of settlement be abolished. This was rejected and the retention of parish responsibility for its own paupers struck another blow at his great objective of freeing the labour market. These alterations crippled the project in many ways. In particular the second and third points robbed the central authority of much of its initiating and discretionary power and left it weakened.

The government followed up its concessions to public opinion by concessions to the old idea of patronage. Patronage was at the heart of government in the 1830s and Chadwick was, in part because of his social origins, not appointed one of the three central commissioners. The posts were raised in salary and by implication in rank from £1,000 to £2,000 per year and men from the ruling political elite were found to fill them. Chadwick, enraged by this situation, did however persuade the Whig government to accept him as a permanent secretary to the commission with the vague understanding that he would be next in line for promotion. This proved the worst of all possible solutions. Of the commissioners, Thomas Frankland Lewis, J.G. Shaw-Lefevre and George Nicholls, only the latter even understood let alone sympathised with Chadwick’s views. The personal antipathy between Chadwick and the Lewises, father and son (the son Cornewall Lewis succeeded his father as commissioner in 1839) meant that from 1837 the commission paid little attention to Chadwick’s advice and from 1838 onwards it practically broke off all relations with him. The poor law administration was from the beginning divided into two camps. Most of the assistant commissioners, the executive in the field sided with Chadwick but they were under the direction and in the power of an increasingly anti-Chadwickian commission. This conflict damaged the effectiveness of administration and Chadwick suffered most from this situation. Public opinion held him responsible for the commission’s policy whereas in fact he had fought against the introduction of a system that was a parody of his own principles and projects and over which he had declining influence.

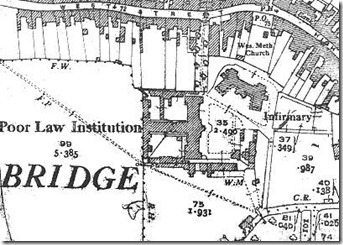

Axbridge workhouse, Somerset

The Act as it was implemented may well have not been what Chadwick intended but he cannot escape some responsibility for this situation. He failed to protest powerfully enough against the dropping of the coercive clauses and had accepted the secretaryship, errors that were not only tactical but political. It is also important to recognise that there were important weaknesses in his conception of the problem of the poor. Chadwick prided himself in the introduction of the ‘reign of fact’ yet his treatment of the problem of the rural poor was seriously flawed. On critical matters such as rural wage rates, actual numbers of unemployed and regional variations, very little reliable data was collected. The Poor Law Report focused on spectacular cases of abuse and described the problem rather than quantified it. It was cast in universal terms but it was really based on one feature of the problem, rural poverty, and even here the issues were misconstrued. Chadwick had little understanding of the nature of urban poverty and that the old poor laws operated differently in towns and cities that in the countryside.

The administrative aspect of his plan also suffered from important weaknesses. The first was the independent status of the central board. In the post-reform politics of the 1830s and 1840s, criticisms and protests about the new poor law were voiced in Parliament where the commissioners had no responsible defender. Separation from parliament far from making the commission strong and fearless, made it weak, confused and extraordinarily subject to political pressures.

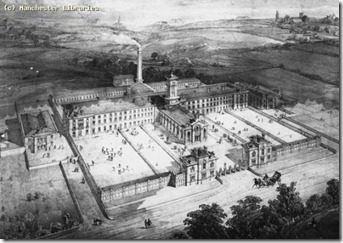

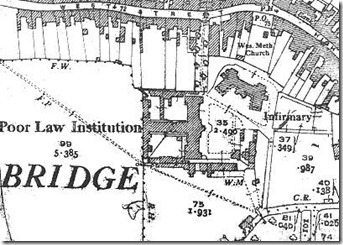

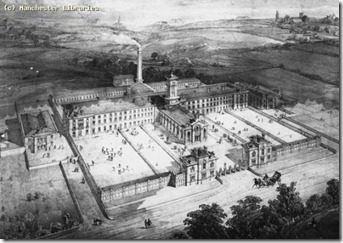

Manchester workhouse

The second great weakness was the power still left to the local authorities. Chadwick refused to go to the full length of centralisation for two reasons. He believed that a national instead of a local poor rate would be too expensive and demanded substantial administrative machinery. He expected that the self-interest of the local guardians would operate in the interests of his general plan and believed that the plan would be more effective if it allowed some degree of representation for local taxation and for the election of members of the Boards of Guardians.[15] In fact, this proved a recipe for confrontation between central and local government: local taxation, because it is collected close to the individual, tends to be less popular than national taxation which often seems more impersonal and local electors also have greater control over the level of that taxation. In all of this the fault was not wholly Chadwick‘s. It was government that had removed its ultimate coercive powers over the local unions from the hands of the commissioners and thus left the 1834 Act more permissive in nature than Chadwick wanted.

Despite the important changes from Chadwick‘s original proposals, much of his work survived and in a few instances his gravest errors were corrected in practice. At the same time some of the foundations of modern central government had been laid. Some problems were left unresolved: the political status of the new type of central commission, its relationship to representative local institutions and central responsibility for the actions of its subordinates. It is also true that without coercive powers the central board could not fully discharge its function and without being subordinate to the cabinet the board could not fully use the coercive powers it retained. These deficiencies were largely remedied by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1847. The substance of centralisation had been established.

To what extent was the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act modelled on Benthamite principles?[16] Jeremy Bentham had been Chadwick’s mentor in the years before his death in 1832.[17] The close connection between Bentham and Chadwick led historians to assume there was a connection between the former’s ideas and the practical solutions put forward by the latter. The question that needs to be addressed is how significant was that connection. Benthamism or Utilitarianism flourished in England in the first half of the nineteenth century though it existed before that and its effect lasted long after. [18] Its main impact came through the writings of Jeremy Bentham and James Mill, and in a modified way through the work of the latter’s son John Stuart Mill. Bentham was eager not only to establish a general formula for the happiness of the community but to discover a method by which to apply this to the detail of reform and his supporters were experts in economics, law, politics and administration. He believed that with a clear first principle, the principle of utility, politics and law need no longer be replete with inconsistency, obscurity, prejudice and confusion.

The cause of all actions, according to Bentham, is always the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. It is clear that Bentham did believe that all values, purposes and goals were reducible to the desire for pleasure and the avoidance of pain but this did not mean that his hedonism was egoistic. Bentham believed that the study of politics, law and society had a moral dimension and in his attempt to create a science of legislation and society he believed that there are three primary tasks: to reduce explanations of human conduct to a single type; to be objective, not to impose his own likes and dislikes, his own standards of value, on the latter being investigated; and, he thought science should be quantifiable and developed the ‘felicific calculus’ to allow this to occur. Bentham maintained that there was a natural harmony of interests between the individual and the community; an individual in pursuing his own interests also pursued the interests of the community. This may have necessitated bringing the interests of the individual into artificial harmony with the interests of the community through the various sanctions open to the community. This had crucial implications for the role of government in society.[19]

The unreformed Poor Law system showed an absence of both uniform policy and central control and was clearly inadequate as a means of dealing with the problems of unemployment and poverty. In Benthamite terms, it was hopelessly outdated and failed to fulfil the principle of utility. Chadwick‘s Report and its principle of ‘less eligibility’ seemed to offer a simple, uniform and economic alternative to the complexity and cost of the old system. In addition to the principle that was to govern poor relief, Chadwick also detailed the administrative change that would be necessary to implement it. However, the underlying belief that the poor could always find work and that relief should only be given in the workhouse, proved to be the undoing of the system. In many areas outdoor relief was still given in recognition of the harsh realities of unemployment, while in other areas wages declined as more people were forced on to the labour market. So the system was often seen as cruel if administered strictly; in order for it to be made more compassionate certain aspects of it had to be evaded.[20] The system of local uniformity under central control and inspection, as recommended by Chadwick, was never put into full operation but was established as the administrative model that was increasingly followed throughout the century.

It is clear that since the Act followed Chadwick‘s Report it was a Benthamite piece of legislation, both in its operational principles and in the administration set up to regulate them. The belief that it was individuals that were being dealt with, not social and economic problems outside the control of individuals; that it was only failed individuals who needed aid and that they should receive it isolated from society; that efficiency and uniformity demanded central control and inspection; all these ideas together were characteristic of the Benthamites but not, taken together, of other reformers, whether political or administrative. The purpose of reform to free the poor and aid the pauper was individualist, but this demanded an increased use of the State as a central authority as the Benthamites emphasised.

Assessing Chadwick’s role in the formulation of the 1834 legislation is a matter on which there has been some debate. In the 1840s and particularly the early 1850s, Chadwick was regarded with considerable suspicion by many of his contemporaries. This was, in part, the result of his prickly character and dogmatic and often overbearing nature. However, Chadwick did attack certain long-established traditions in British administration and social policy. His Benthamism and middle-class origins made him suspect in a bureaucracy still dominated by aristocratic patronage. The notion of a Civil Service grounded in merit and ability was still in the future. Added to this he was politically pushy and easily offended. His belief in a uniform system of poor law administration under central control offended those who believed in local autonomy and, within the limits of nineteenth century definitions, in ‘democracy’. This helps to explain why no uniform system was introduced in the 1830s and was even more an issue when Chadwick moved into public health and the need to legislate positively in favour of cleaner towns. It is not surprising that Anthony Brundage called his study of Chadwick England’s ‘Prussian Minister’, a term of contemporary abuse drawing comparisons between Chadwick’s centralisation and the militaristic and highly centralist Prussian State.

[1] Slack, P., The English poor law, 1531-1782, (Macmillan), 1990 and Marshall, J.D., The Old Poor Laws 1795-1834, (Macmillan), 2nd ed., 1985 are brief bibliographical essays. Fideler, Paul A., Social welfare in pre-industrial England: the old Poor Law tradition, (Palgrave), 2006 is a more recent study. Hitchcock, Tim, King Peter and Sharpe, Pamela, (eds.), Chronicling Poverty: The Voices and Strategies of the English Poor 1640-1840, (Macmillan), 1997 and Lees, Lynn Hollen, The Solidarities of Strangers: The English Poor Laws and the People 1700-1948, (Cambridge University Press), 1998 take a longer perspective and are highly innovative studies.

[2] Innes, Joanna, ‘The distinctiveness of the English poor laws, 1750-1850’, in Winch, D.N. and O’Brien, P.K., (eds.), The political economy of British historical experience, 1688-1914, (Oxford University Press), 2002, pp. 381-407. Valuable local studies include Adams, Jenny, ‘The old poor law in Suffolk, 1727-1834’, Suffolk Review, 47 (2006), 2-27 and Hampson, E.M., Treatment of Poverty in Cambridgeshire 1587-1834, (Cambridge University Press), 1934, reprinted 2009.

[3] Neuman, Mark, ‘A suggestion regarding the origins of the Speenhamland plan’, English Historical Review, Vol. 84, (1969), pp. 317-322, Speizman, M.D., ‘Speenhamland: an experiment in guaranteed income’, Social Service Review, Vol. 40, (1966),pp. 44-55, Williams, Samantha, ‘Malthus, marriage and poor law allowances revisited: a Bedfordshire case study, 1770-1834’, Agricultural History Review, Vol. 52, (2004), pp. 56-82 and ‘Poor relief, labourers’ households and living standards in rural England c.1770-1834: a Bedfordshire case study’, Economic History Review, Vol. 58, (2005), pp. 485-519.

[4] The debate over the poor laws is best approached through Poynter, J.R., Society and Pauperism: English Ideas on Poor Relief 1795-1834, (Routledge), 1969 and Cowherd, R.G., Political Economists and the English Poor Laws, (Ohio University Press), 1978. Boyer, G.R., An Economic History of the English Poor Law 1750-1850, (Cambridge University Press), 1990 is an important defence of Malthusian ideas. Himmelfarb, G., The Idea of Poverty: England in the Early Industrial Age, (Faber), 1984 is an extensive work on the subject. Brundage, Anthony, The English poor laws, 1700-1930, (Palgrave), 2002, provides a convenient overview.

[5] Boyer, G.R., ‘Malthus was right after all: poor relief and birth rates in southeastern England’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 97, (1989), pp. 93-114

[6] Blaug, Mark, ‘The myth of the old Poor Law and the making of the new’, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 23, (1963), pp. 151-184 remains an important paper. See also, Taylor, J.S., ‘The mythology of the Old Poor Law’, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 29, (1969), pp. 292-297.

[7] Royal commission on administration and practical operation of the Poor Laws, Report and appendices, (Parliamentary papers, H.C. (1834) XXVII; Parliamentary papers, H.C. (1834) XXVIII), 1834.

[8] Blaug, M., ‘The Poor Law report reexamined’, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 24, (1964), pp. 229-245.

[9] See, Dunkley, P., ‘Whigs and paupers: the reform of the English poor laws, 1830-1834’, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 20, (1981), pp. 124-149 and ‘Paternalism, the magistracy and poor relief in England, 1795-1834’, International Review of Social History, Vol. 24, (1979), pp. 371-397.

[10] Brundage, A., The Making of the New Poor Law: the politics of inquiry, enactment and implementation, 1833-39, (Hutchinson), 1979, Checkland, S.G. and E., (eds.), The Poor Law Report of 1834, (Penguin), 1974, Digby, A., The Poor Law in Nineteenth Century England and Wales, (The Historical Association), 1982, Fraser, Derek, (ed.), The New Poor Law in the Nineteenth Century, (Macmillan), 1976, Rose, M.E., The Relief of Poverty 1834-1914, (Macmillan), 2nd ed., 1985 and Wood P., Poverty and the Workhouse in Victorian England, (Alan Sutton), 1991 are the most useful books on the introduction and operation of the ‘new’ poor law.

[11] Poverty in the cities is analysed by Treble, J., Urban Poverty in Britain 1830-1914, (Batsford), 1979, Rose, L., ‘Rogues and Vagabonds’ Vagrant Underworld in Britain 1815-1985, (Routledge), 1988 and Chinn, Carl, Poverty amidst prosperity: the urban poor in England 1834-1914, (Manchester University Press), 1995.

[12] Ibid, Checkland, S. and E., (eds.), The Poor Law Report of 1834, pp. 91-92.

[13] Ibid, Henriques, Ursula, Before the Welfare State, p. 59.

[14] Besley, Timothy, Coate, Stephen and Guinnane, Timothy W., ‘Incentives, information, and welfare: England’s New Poor Law and the workhouse test’, in Guinnane, Timothy W., Sundstrom, William A. and Whatley, Warren, (eds.), History matters: essays on economic growth, technology, and demographic change, (Stanford University Press), 2004, pp. 245-270.

[15] See, Brundage, A., ‘Reform of the Poor Law electoral system, 1834-94’, Albion, Vol. 7, (1975), pp. 201-215 on local elections.

[16] Winch, D., Riches and poverty: an intellectual history of political economy in Britain, 1750-1834, (Cambridge University Press), 1996 provides the intellectual background.

[17] Ibid, Finer, S.E., The Life and Times of Sir Edwin Chadwick, pp. 28-37.

[18] Pearson, Robert and Williams, Geraint, Political Thought and Public Policy in the Nineteenth Century, (Longman), 1984, pp. 9-38 is perhaps the simplest introduction to a complex issue. See also, Quinn, Michael, ‘A Failure to Reconcile the Irreconcilable? Security, Subsistence and Equality in Bentham’s Writings on the Civil Code and on the Poor Laws’, History of Political Thought, Vol. 29, (2008), pp. 320-343 and Schofield, Philip, Utility and democracy: the political thought of Jeremy Bentham, (Oxford University Press), 2006.

[19] See, Roberts, David, ‘Jeremy Bentham and the Victorian administrative state’, Victorian Studies, Vol. 2, (1959), pp. 193-210.

[20] Henriques, U.R.Q., ‘How cruel was the Victorian Poor Law?’, Historical Journal, Vol. 11, (1968), pp. 365-371.