The 1820s is often written off as a decade of little radical activity yet it was during these years that Britain became a manufacturing society. Whether factories and firms were small or larger-scale, whether increases in productivity were achieved by increasing the labour force or using machine technology, whether growth was achieved using skilled or unskilled labour or in urban or rural settings, British society was increasingly and irrevocably manufacturing in its emphasis. The relative stability and long perceived certainties of pre-industrial Britain were replaced by the vibrancy, uncertainties and class tensions of a free market economy and modernising society.

The economy revived in the early 1820s and there was a decline in radical political activity, something that reinforces the link between poor economic conditions and concerted radical action. But popular radicalism always meant more than demanding inclusion in the political system and embraced a range of causes of beliefs. Some radicals focused on building cooperative institutions such as trade unions, friendly societies, mutual aid societies and Mechanics Institutes. Others sought greater religious equality for nonconformists and to establish a system of secular education. Many nonconformists also were radical in their politics because they objected that being a member of the established Church of England gave individuals important legal privileges denied to nonconformists. Religious issues could stir deeper passions than politics and the religious question, as contemporaries called it, was a key political issue for most of the century.

Some workingmen turning to religion--there were revivals in particularly in the north and south-west. There was, for instance, a Primitive Methodist revival among lead miners in Weardale and more generally across the North-East in 1822 and 1823. [1] Revivalism in the 1820s occurred largely in areas with a significant rural population. Primitive Methodism was largely rural in character and, with the exception of the North-East and the Potteries; its main strength was in the largely agricultural counties of England. It was not until after 1850 that its appeal to the urban worker became obvious. Primitive Methodism was the medium through which agricultural labourers could fight for social and economic recognition and its chapels provided rural workers with a symbol of independence and defiance of the established social order.

While Primitive Methodism represented a radical theology, Wesleyan Methodism was increasingly strident in its support for the existing social order and, under the influence of Jabez Bunting, large numbers of people were expelled for radical activities. Growth in the northern manufacturing districts came to a halt and even went into temporary decline in 1819 and 1820 and in Rochdale there was a fifteen per cent decrease in membership between 1818 and 1820.[2] Although Bunting and his supporters recognised the value of revivalism and encouraged it so long as it did not disrupt regular circuit life and could ideally be managed, they disapproved of some of its methods, especially ranting and disassociated themselves from the emotionalism of Primitive Methodism.[3] This, and John Wesley’s policy before his death in 1791 which was continued by his successors of concentrating on evangelising urban areas where the Church of England was failing in its functions, meant that the links between Methodism and urban radicalism were loosening, although the extent to which this occurred varied from locality to locality. This view of Methodism, akin to E. P. Thompson’s excoriating critique of the movement as an instrument of social control, neglects the internal battles of the 1790s and early years of the nineteenth century in industrial towns over lay participation in church governance, control over Sunday schools and the extent of denominational control over the political activities of its members. In the 1820s, its nature as a popular movement meant that it could still undermine the established order of Church and State even if, by 1850, its role as an alternative national faith had evaporated. [4]

The 1820s also represented a critical decade for workers in textile industries as it saw an intensification of the demise of handloom weaving. The introduction of powered spinning largely in spinning factories from the 1780s resulted in surging production of yarn that had to be woven on handlooms by weavers whose numbers in Britain reached a peak of about 240,000 workers in 1820. For several generations, handloom weavers had enjoyed high prices, a relatively good standard of living and benefitted from increasing demand for the products of their looms. They were also vocal in defence of their livelihood with, for instance, 130,000 signing a petition in 1807 calling for a minimum wage and the following year, some 15,000 attended a demonstration in Manchester. The development of a reliable power loom by Richard Roberts, a Manchester engineer, in 1822—he also perfected a fully mechanised self-acting mule for spinning between 1825 and 1830—led to the rapid adoption of powered weaving. Edward Baines estimated that there were 2,400 power looms in British factories in 1813, 14,150 in 1820 but over 115,000 by 1835. This shift placed handloom weaving under growing pressure, its profitability tumbled and the numbers of handloom weavers in Lancashire fell from between 150,000 to 190,000 in 1821 to about 30,000 by 1861.

The decline in handloom weaving was uneven with some millowners using both machinery and hand-working while some weavers used finer grades of cotton, which early power looms could not weave, or turned to silk that remained largely unmechanised. Even so, handloom weaving was in terminal decline and, as many children of handloom weavers did not follow their fathers in the trade, it was increasingly characterised by an ageing workforce. [5] By the late 1820s, progressive cuts in wage-rates left many handloom weaving families with serious economic problems. Handloom weavers who move into urban areas might mitigate this by deploying women or children in the factory labour market while those weavers who remained in rural areas could take advantage of supplementary earning opportunities afforded by farming and mining. Nonetheless, by 1830 both sets of weavers found themselves in endemic structural poverty unable to generate sufficient income to cover basic costs and heavily dependent on poor relief.

The idea of a government-applied minimum wage to give give handloom weavers a degree of security was still being suggested and not just by the weavers. Some of the more respectable ‘putting-out’ firms, facing competition from machine-weaving businesses who undercut them by paying their unskilled workers low wages, saw the benefits of such a scheme. In September, 1819, a month after the Peterloo Massacre, 35 calico producers supported the call for a minimum weavers' wage and as late as 1822, several manufacturers met in Rossendale to demand restrictions on the use of power looms. The Committee of Manchester Weavers joined the outcry, claiming:

The evils of multiplying power looms, by first ruining half a million who depend on manual weaving (he was presumably referring to families rather than individuals), and especially those unhappy young people they now employ, are such as no human being can think are counterbalanced by any good expected from them.

Having repealed the legislation that might have protected weavers in 1809, the government was unwilling to introduce obstacles to the free market accelerating the trend towards mechanisation and it was not until 1834-1835 that a Select Committee examined the problems faced by weavers. James Hutchinson, one of the calico producers who had protested in 1819, like many of his fellow businessmen, finally opened his own power-loom mill at Woodhill, Elton.

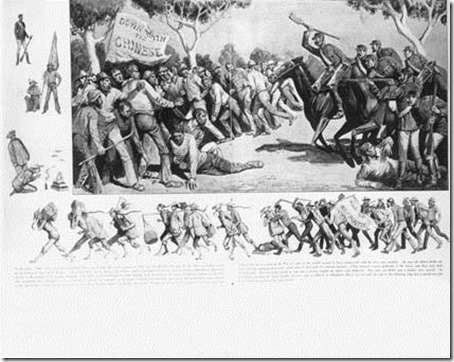

Handloom weavers publicised their plight whenever the opportunity arose. Actress Fanny Kemble, one of the guests at the opening on the Liverpool-Manchester Railway in 1830, described the arrival of the first train into Manchester, packed with dignitaries including Wellington:

High above the grim and grimy crowd of scowling faces, a loom had been erected, at which sat a tattered, starved-looking weaver, evidently set there as a representative man, to protest against the triumph of machinery and the gain and glory which the wealthy Liverpool and Manchester men were likely to derive from it. [6]

For radicals such as Peter Murray McDouall writing in his Chartist and Republican Journal in 1841, the gradual disappearance of handloom weavers, represented the destruction of independence, family economy and control over the pace and nature of work and the creation of wage slavery by ‘factory slaves’ within the developing factory system of industrial capitalism.

Other radicals campaigned successfully against the Combination Acts leading to their repeal in 1824. A downturn in the economy led to a rapid increase in trade union activity with extensive strikes, including some violence in the winter of 1824-1825. Employers lobbied for the reintroduction of the Combination Acts and in 1825 new legislation was passed allowing unions to negotiate over wages and conditions but without the legal right to strike. This effectively limited trade unions to peaceful collective bargaining with employers and if they went beyond this narrow definition of legal activity for trade unions, they could be prosecuted for criminal conspiracy. Faced with technological change and the considerable powers left to employers after 1825, workers were increasingly convinced that small unions could never succeed. What was needed, some argued, were national or general unions representing all the workers in a particular trade from different parts of the country. In 1829, John Doherty, leader of the Lancashire cotton spinners formed a Grand General Union of Spinners. For greater negotiating power, the next step was to try to unite all unions in all trades into a single union. He formed the National Association for the Protection of Labour in late 1829 in Manchester and it spread into the neighbouring cotton towns the following year and subsequently into other manufacturing areas especially the East Midlands. [7]

The 1820s also saw a refinement of working-class analysis of the exploitative nature of the economy. [8] William Cobbett’s solution was to get rid of the system of corruption, the national debt and paper money and he implied that life would revert to the patterns of the past; little analysis, simply populist nostalgia. By contrast, Thomas Spence, William Ogilvie, Thomas Hodgskin, William Thompson, Robert Owen, John Gray and later John Francis Bray, Ernest Jones, James ‘Bronterre’ O’Brien and George Harney argued that the rights of man must be grounded in the possession of economic power. Their anti-capitalist and socialist political economies stood in stark contrast to the classical political economies of James and John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, Robert Torrens, John Ramsey McCulloch and Nassau Senior. [9]

Robert Owen had outlined his cooperative views in A New View of Society in 1813. Although Owen was influential in the working-class movement in the early 1830s, he sought social reform from above, a reflection of his elitist and paternalist attitudes. His reform programme was not confrontational: he saw his reforms as a means of avoiding class conflict, violent protest and revolution. His most important contribution was seeing capitalism not as a collection of discrete events but as a system. Throughout the 1820s, a growing group of labour radicals embraced Owen’s critique of capitalism and his views on cooperation. Thompson, Hodgskin and Gray articulated not simply the theoretical basis for a distincly anti-capitalist political economy but also considered its scope, methods, content and aims. All were, to a degree, Ricardian socialists who adopted the labour theory of value while rejecting the elements of Ricardo’s model that claimed capital, too, was productive. Hodgskin, for instance, argued that capitalists were parasites who diverted the fruits of labour’s productivity into unproductive consumption.

Thompson rejected the notion, expressed particularly by Thomas Malthus that any increase in the wages of labourers could only lead to their further immiseration. [10] Hodgskin, though he rejected Thompson’s cooperative views, suggested:

…the real business of men, what promotes their prosperity, is always better done by themselves than by any few separate and distinct individuals, acting as a government in the name of the whole.[11]

In 1825, in his Labour Defended Against the Claims of Capital, he argued that free-trade economists had invested ‘capital’ with productive powers that it did not possess and that capitalists could only grow rich where there was an oppressed group of workers kept in poverty. Writing in the aftermath of the repeal of the Combination Acts in 1824 and the repressive legislation the following year, Hodgskin believed that laws against trade unions and collective bargaining had created an unfair advantage against workers in favour of capitalists and that the large profits made by capitalists were not the result of natural economic forces but were generated by the coercive power of government. Only with the freedom of the free market, he maintained, could labourers of every kind receive just compensation for their work. Economic intervention by governments could do nothing to increase wealth or to accelerate its progress and that the laws of economics would only have the power to transform society when unrestricted by arbitrary legal systems. [12]

John Gray argued that the producers receive only about a fifth of the value of their products, whereas their labour creates all of that value. [13] However, he did not believe that this issue could be resolved by the unrestricted operation of the free market arguing that free market competition hampered the economy’s productivity because incomes remain low, limiting demand and therefore production. The market was seen as a source of exploitation and economic depression and the competitive pressures unleashed by the market resulted in socially destructive and morally corrosive behaviour. To overcome the limits competition places on social production and the hardships it imposes, Gray proposed a communitarian solution. What was necessary, Gray maintained, was central direction and control over the industrial economy by a National Chamber of Commerce, which would own the means of production, as a way of achieving certain socialist objectives. He also called for the formation of a National Bank that would ensure that money would increase as product increased and decrease as produce was consumed or redemanded as well as a system of cooperative associations to organise supply and demand. In this way, Gray believed that economic activity could be managed to ensure distributive and commutative justice, price stability, efficient allocation of resources and an end to economic depression resulting from supply outstripping effective supply.

The major problem with populist anti-capitalist thinking in the 1820s was that it lacked a comprehensive understanding of the nature of the causes of the exploitation and alienation of capitalism. Largely because of their failure to address this issue, Thompson sought to establish cooperative solutions irrespective of what was going on in the wider capitalist society. His solution was not to replace the existing capitalist system but to circumvent it by creating separate cooperative communities. The communities established by Robert Owen failed to translate the theory of cooperative living into communities that worked largely because of his paternalistic and undemocratic approach to running them and their need to operate within a capitalist environment. Gray, however, went further in suggesting socialist solutions to replace market capitalism. Although anti-capitalist economists had developed an effective critique of capitalism in the 1820s and this continued into the 1830s, what they had not done was to link their critique to the question of parliamentary reform. It was the publication of the Poor Man’s Guardian, edited by Bronterre O’Brien that proved crucial. Although strongly influenced by the popular economists and by Owen, he rejected Owen’s opposition to political action. He transformed the traditional rhetoric of radicalism by treating parliamentary reform as meaningless on its own. Without social and economic transformation, he argued, parliamentary reform could not address the ills of the working-classes.

[1] Patterson, W. M., Northern Primitive Methodism, (E. Dalton), 1909, pp. 154-170.

[2] Engemann, T. S., ‘Religion and political reform: Wesleyan Methodism in nineteenth-century Britain’, Journal of Church & State, Vol. 24, (1982), pp. 321-336, provides a good summary. Hempton, David, The Religion of the People: Methodism and Popular Religion, c1750-1900, (Routledge), 1996, pp. 162-178, is excellent on the historiography.

[3] Hempton, D., Methodism and Politics in British Society 1750-1850, (Hutchinson), 1984, Edwards, M., After Wesley: a study of the social and political influence of Methodism in the middle period, 1791-1849, (Epworth Press), 1948, Taylor, E. R., Methodism and Politics 1791-1851, (Cambridge University Press), 1935, and Wearmouth, R. F., Methodism and the Working-class Movements of England 1800-1850, (Epworth Press), 1937.

[4] Ibid, Hempton, David, The Religion of the People: Methodism and Popular Religion, c1750-1900, pp. 170-171.

[5] Bythell, Duncan, The Handloom Weavers: A Study in the English Cotton Industry During the Industrial Revolution, (Cambridge University Press), 1969, Nardinelli, Clark, ‘Technology and Unemployment: The Case of the Handloom Weavers’, Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 53, (1), (1986), pp. 87-94, and Timmins, Geoffrey, The Last Shift: The Decline of Handloom Weaving in Nineteenth-Century Lancashire, (Manchester University Press), 1993.

[6] Kemble, Frances Ann, Records of a Girlhood, (R. Bentley & Son), 1878, p. 304.

[7] The development of trade union is explored in greater detail.

[8] Thompson, Noel W., The People’s Science: The popular political economy of exploitation and crisis 1816-34, (Cambridge University Press), 1984, and The Real Rights of Man: Political Economies for the Working Class, 1775-1850, (Pluto Press), 1998.

[9] McNally, David, Against the Market: Political Economy, Market Socialism and the Marxist Critique, (Verso), 1993, pp. 104-138.

[10] Thompson, William, An Inquiry into the Principles of the Distribution of Wealth Most Conducive to Human Happiness; applied to the Newly Proposed System of Voluntary Equality of Wealth, (Longman, Hurst Rees, Orme, Brown & Green), 1824, and Labor Rewarded. The Claims of Labor and Capital Conciliated: or, How to Secure to Labor the Whole Products of Its Exertions, (Hunt and Clarke), 1827.

[11] Hodgskin, Thomas, Travels in the North of Germany: Describing the Present State of the Social and Political Institutions, the Agriculture, Manufactures, Commerce, Education, Arts and Manners in that Country Particularly in the Kingdom of Hannover, 2 Vols. (Constable), 1820, Vol. 1 p. 292.

[12] Slack, David, Nature and Artifice: The Life and Thought of Thomas Hodgskin (1787-1869), (Boydell), 1998, pp. 89-136, considers his thinking in the 1820s.

[13] Gray, John, Lecture on Human Happiness: Being the First of a Series of Lectures on that Subject in which Will be Comprehended a General Review of the Causes of the Existing Evils of Society, and a Development of Means by which They May be Permanently and Effectually Removed, (Sherwood, Jones & Company), 1825, and The Social System: A Treatise on the Principle of Exchange, (Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green), 1831. See also, DLB, Vol. 6, pp. 121-125, and Kimball, J., The Economic Doctrines of John Gray, 1799-1883, (Catholic University of America Press), 1946.