The Reform Act 1832, traditionally regarded as the beginnings of middle-class political power, does not provide an index of the rise to power of the industrial bourgeoisie.[1] The new franchise increased the representation of the urban middle-class but it was also designed to reduce the power of newly wealthy owners of corrupt boroughs and to restore and give fresh legitimacy to the traditional influence of the landed interest. As late as the 1860s, almost two-thirds of the country’s MPs came from landed backgrounds, over one-third, hereditary aristocrats and around half of the cabinets of both parties were still aristocratic.[2] It was not until after the Reform Act 1867 that the first major changes in the nature of the political elite began to emerge. The Act extended the franchise to certain sections of the urban working-classes and this led to the replacement of local patterns of influence with professionally organised political machines. This was accelerated by further extensions of the franchise in 1884 but also by such reforms as the Secret Ballot Act 1872, the restriction of candidates’ spending on elections by the Corrupt Practices Act 1883, the dilution of the aristocracy through awards of peerages in recognition of wealth and political service that began in 1885 and the establishment of elections for local government in the counties in 1888 and 1894.

It is probably fair to talk of a major restructuring of the British Establishment from the 1870s but the extent to which the middle-classes as a whole benefitted from this was limited. It did not give the provincial manufacturers a greatly enhanced position at national level.[3] Membership of the ruling circle was being extended to include larger numbers of bankers and merchants but few manufacturers. However, though the great country houses were being displaced from the centre of political power, the network of power and influence was based even more firmly in the south of the country and the aristocracy still remained the leading group within the ruling classes. Who held what position and what social classes they came from may be less important than how and in whose interests they acted.

It can be argued that the industrial bourgeoisie was able to exert sufficient pressure on the nation’s political elite to get the kind of government it wanted. However, the challenge to which the restructuring of the Establishment was a response came less from industrial employers than from occupationally-based pressure groups among both the professional middle-classes and the working-classes that had been able to win major reforms in the 1860s and 1870s and were to make important advances in the 1890s and 1900s.

Lancashire factory owners became a substantial group in the House of Commons after 1832 but their effectiveness was limited by internal political divisions and by their inability to create external alliances with other parliamentary groupings. [4] In the longer term, factory owners became less active in politics and more conservative in their social behaviour. Their strong attachment to the Tory Party echoed the traditional allegiance of the Lancashire aristocracy. The one apparent assertion of industrial against the landed interest was the debate over the Corn Laws that led to their eventual repeal in 1846. The Anti-Corn Law League was a popular radical campaign that secured an unusual amount of financial backing from manufacturers because of the economic benefits they expected. Repeal was beneficial to manufacturers who had a direct interest in reducing food prices but it was by no means disadvantageous to the aristocracy much of whose land was devoted to pastoral farming and whose rents from arable land were largely maintained during the long mid-century boom. It was the tenant farmer who stood to suffer most. Repeal was a result of aristocratic concession to popular opinion during a short-term crisis rather than of the long-term growth of bourgeois political power.[5]

The middle-class ‘victory’ of 1846 was atypical of their success in this period and did not mark the beginnings of middle-class control of the political system. This explains why the limitation of the hours of work in factories contained in the 1847 Factory Act was passed in the face of strong opposition from most of the Lancashire manufacturers and why it was a further twenty years before the next instalment of parliamentary reform. Similar pattern can be seen in the 1870s, not only in the widespread aristocratic support for agricultural labourers’ demands but also in government attitudes towards labour policy in general. The main line of government policy was a liberal one of not only recognising but even strengthening the rights of employees to bargain collectively over wages and conditions. It had been possible for Britain’s ruling elite, based as it was on landownership, commerce and increasingly on foreign finance, to maintain social stability through liberal concessions to pressure from below without having the sacrifice its own immediate political and economic interest.

So if the position of manufacturers within the British ruling classes was marginal, what power did they have within their own industrial regions? Given their wealth, it would not be surprising if they exercised considerable local power but, at least within the political arena, there were limitations on that power. First, aristocratic influences persisted in many industrial towns until at least the 1870s acting as a counterbalance to the economic and political impact of the factory elite. Secondly, there were other competing non-landed groups, above all the mercantile, retailing and professional middle-classes, who were generally more active in local urban politics than manufacturers. In Bolton and Salford, for example, over half the councillors in the 1840s had been manufacturers but this had fallen to under 40% by the 1870s and continued to decline thereafter. The political dominance of manufacturers was confined to the smaller industrial towns but even there it was not unlimited. The growing powers of local government acquired either by special parliamentary private bills or by national permissive legislation led to the establishment of more democratic local procedures.

The middle-classes had a relatively lowly status in terms of wealth-holding and political power, but can they be seen as a leading or ‘hegemonic’ class in terms of its ability to shape policy through its impact on the attitudes and values of the country as a whole? How far did the middle-classes mould society in their own image and indirectly influence the behaviour of the more prominent actors, who were after all themselves major property owners? Harold Perkin contrasted the ‘entrepreneurial ideal’ of the emergent middle-classes with the ‘aristocratic’ ideal but this characterisation has been questioned. It is difficult to define ‘bourgeois’ as opposed to ‘aristocratic’ values and it is perhaps better to focus on the simpler questions of whether the specific interests of manufacturers were represented in the attitudes and values of the ruling classes.[6]

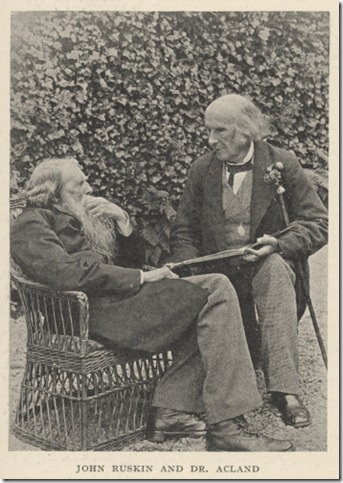

If the country’s literary culture is taken as an index of the concerns of its rulers, it is clear that in Britain manufacturers, far from reshaping dominant attitudes, were consistently rejected unless they conformed to existing social values. Economic success was viewed with some suspicion and the early-modern notion that money was rootless and without the reciprocal obligations and duties of landowning retained its potency. Until the 1760s, attitudes were ambiguous, but thereafter the trend was distinctly towards literary condemnation of new wealth reaching its peak in the rejection of provincial manufacturers between the 1840s and the 1930s. The only route to acceptance and ‘respectability’ was to adopt the values of civilised culture and public service associated with the ‘gentleman’, and later the professional man and to abandon the values of mere money-making and sectional interest associated with new wealth.[7] These elite values had an effect on the industrial bourgeoisie itself. Many of its members lived in town houses or holidayed at coastal resorts located on large landed estates. Most aspired to acceptance by the Establishment. The wealthier sent their sons to public schools and bought their own landed estates. Those who were active in political life did so in the Conservative and Liberal parties led by the aristocracy.[8] It is, however, clear that there was a significant space for the cultural influence of non-landed groups within the industrial regions. As with political influence, merchants, retailers and professionals were just as active, if not more so, than manufacturers and there were important political and religious differences within local middle-classes.

[1] Garrard, John Adrian, ‘The middle classes and nineteenth century national and local politics’, in Garrard, John Adrian, Jary, David, Goldsmith, Michael and Oldfield, Adrian, (eds.), The middle class in politics, (Saxon House), 1978, pp. 35-66 and Briggs, Asa, ‘Middle-class consciousness in English politics, 1780-1846’, Past & Present, Vol. 9, (1956), pp. 65-74 provide a brief overview.

[2] Ibid, Searle, G.R., Entrepreneurial Politics in Mid-Victorian Britain, is the clearest statement of the position of the middle-classes in politics.

[3] The economic strength of this group, measured in terms of their share of the national wealth, began to decline from the 1870s under pressure from foreign competition.

[4] Kadish, A.’, Free trade and high wages: the economics of the Anti-Corn Law League’, and Lloyd-Jones, Roger, ‘Merchant city: the Manchester business community, the trade cycle, and commercial policy, c.1820-1846’, in Marrison, Andrew (ed.), Freedom and trade, Vol.1: Free trade and its reception, 1815-1960, (Routledge), 1998, pp. 14-27, 86-104.

[5] Adelman, Paul, Victorian Radicalism: The Middle-Class Experience 1830-1914, (Longman), 1984, pp. 11-28 and Chaloner, W.H., ‘The Agitation against the Corn Laws’ in Ward, J.T., (ed.), Popular Movements 1830-1850, (Macmillan), 1970, pp. 135-151 are good summaries of the work of the Anti-Corn Law League. McCord, N., The Anti-Corn Law League 1838-1846, (Allen and Unwin), 1958 and Pickering, Paul A and Tyrrell, Alex, The People’s Bread: A History of the Anti-Corn Law League, (Leicester University Press), 2000 provide different perspectives but Prentice, Archibald, History of the Anti-Corn Law League, 2 Vols. 1853, new edition with an introduction by W.H. Chaloner, (Cass), 1968, is still a valuable source. The political strategies of the League can be approached through Hamer, D.A., The Politics of Electoral Pressure, (Harvester), 1977, pp. 58-90 and Prest, J., Politics in the Age of Cobden, (Macmillan), 1977, especially chapters 5 and 6.

[6] Gunn, Simon, The public culture of the Victorian middle class: ritual and authority in the English industrial city, 1840-1914, (Manchester University Press), 2000 and Kidd, Alan J. and Nicholls, David, (eds.), Gender, civic culture, and consumerism: middle-class identity in Britain, 1800-1940, (Manchester University Press), 1999, Green, S., ‘In search of bourgeois civilisation: institutions & ideals in 19th century’, Northern History, Vol. 28, (1992), pp. 228-245 and Morgan, S., ‘‘A sort of land debatable’: Female influence, civic virtue and middle-class identity, c.1830-c.1860’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 13, (2004), pp. 183-210.

[7] See one dimension in Jeremy, David J., (ed.), Religion, business, and wealth in modern Britain, (Routledge), 1998.

[8] MacLeod, Dianne Sachko, Art and the Victorian middle class: money and the making of cultural identity, (Cambridge University Press), 1996.