An alternative to the vertical relationships of a paternalistic hierarchical society lay in the horizontal solidarities of ‘class’.[1] Richard Dennis, in his study of nineteenth century industrial cities, sums up the problem of class in the following way:

Evidently the road to class analysis crosses a minefield with a sniper behind every bush.... it may not be possible to please all the people all of the time...[2]

What did contemporaries understand by the idea of ‘class’? How many classes were there? What do historians understand by ‘class consciousness’ and how, if at all, does it differ from ‘class perception’? When did a working-class come into existence? Despite all the literature on the subject, the years since the publication of E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working-Class in 1963, have done little to clarify the situation. Answers to the central questions of ‘when?’, ‘how?’ and ‘why?’ have been surprisingly inconclusive. [3]

Many contemporaries interpreted early Victorian society in terms of two classes. Disraeli popularised the idea of ‘two nations’, the rich and the poor.[4] Elizabeth Gaskell wrote of Manchester that she had ‘never lived in a place before where there were two sets of people always running each other down.’[5] Tory Radicals were not alone in using the two-class model. Engels referred to the working-class in the singular and offered a model dominated by two classes, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, in which other classes existed but were becoming increasingly less important. Marxist historians, E.P. Thompson and John Foster, have also used this model. For Thompson, class experience was largely the result of the productive relations into which people entered. The essence of class lay not in income or work but in class-consciousness, the product of contemporary perceptions of capital and labour, exploiter and exploited. [6]

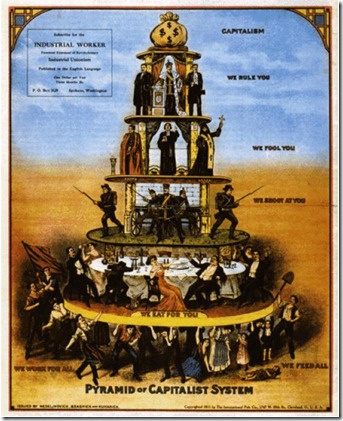

From the Industrial Worker, 1911

John Foster, in his study of Oldham, South Shields and Northampton, found that 12,000 workers sold their labour to 70 capitalist families. [7] There was a middle-class of tradesmen, shopkeepers and small masters but despite deep divisions in their social and political behaviour they aligned with the working-class on most political issues.[8] The working-class, Foster argues, went through three stages of developing consciousness. It was, first, ‘labour conscious’ when consumer prices ceased to be a major concern for workers and the focus shifted to the levels of their own wages.[9] Then ‘class conscious’ where attempts to resolve industrial and economic problems, initially by a vanguard of skilled workers, became politicised. This can be seen in the 1830s and 1840s in working-class support for the Chartist movement.[10] Political reform was seen as a necessary prerequisite for the resolution of economic problems: only a Parliament elected on the Charter would be prepared to legislate in favour of working-class concerns. Foster argues that the movement was a victim of its own success and that the bourgeoisie was alerted to the threat from the potentially revolutionary masses and adopted a policy of economic liberalisation by conceding some proletarian demands. Foster specifically mentioned the Ten Hour Act 1847 and the offer of household suffrage in 1849. This, he maintained, represented a major tactical victory and led to a ‘liberalised consciousness’ by which the bourgeoisie, aided by growing economic prosperity after 1850, was able to attach important sections of the working population to its consensus ideology grounded in individualism and ‘respectability’.[11] The skilled workers who had previously formed the revolutionary vanguard sold out in the post-Chartist years and became reformist in attitude, accepting the economic situation as it was and working to get the best deal out of it they possibly could.

It is possible to criticise the two-class model in a variety of ways. It assumes a model for change based on conflict or ‘class war’ between two competing classes for economic dominance. It accepts other social groups, but subsumes them within the two-class perspective. It recognises that although a significant degree of ideological homogeneity that may have validity in the vibrant social magma of the industrial factory towns, it has less validity in rural areas and the older urban areas. Diversity of experience within the working population led to diversity of responses.

[1] The literature on ‘class’ is immense but theoretical perspectives can be found in Calvert, P., The Concept of Class, (Hutchinson), 1983, Giddens, A., The Class Structure of Advanced Societies, (Hutchinson), 1973 and especially Neale, R.S., (ed.), History and Class: essential readings in theory and interpretation, (Basil Blackwell), 1984.

[2] Dennis, R., English Industrial Cities in the Nineteenth Century: A Social Geography, (Cambridge University Press), 1984, pp. 187-188.

[3] Neale, R.S., Class in British History 1680-1850, (Basil Blackwell), 1983 and Class and Ideology in the Nineteenth Century, (Routledge), 1972, the useful bibliographical essay by Morris, R.J., Class and Class Consciousness in the Industrial Revolution, (Macmillan), 1980 and his ‘The industrial revolution: Class and Common Interest’, History Today, Vol. 33, (5), (1983), pp. 31-35 are good starting points for the period before 1850. See also, Briggs, A., ‘The language of ‘class’ in early nineteenth century England’, in Briggs, A. and Saville, J., (eds.), Essays in labour history in memory of G.D.H. Cole, rev. edn., (Macmillan), 1967, pp. 43-73 and Jones, G. Steadman, Languages of Class, (Cambridge University Press), 1983. Joyce, Patrick, Visions of the People: Industrial England and the question of class 1840-1914, (Cambridge University Press), 1991 takes the question of language further and questions the veracity of a view of society grounded simply in ‘class’. Other studies include Prothero, I., Artisans and Politics in Early Nineteenth-Century London, (Dawson), 1979, Smith, D., Conflict and Compromise: Class Formation in English Society 1830-1914, 1982 and Calhoun, C., The Question of Class Struggle, (Basil Blackwell), 1982. Reid, Alastair J., Social Classes and Social Relations in Britain 1850-1914, (Macmillan), 1992 is the best and briefest starting-point for this period. Benson, J., The Working-class in Britain 1850-1939, (Longman), 1989 is the most recent general survey. McKibbin, R., The Ideologies of Class: Social Relations in Britain 1880-1950, (Oxford University Press), 1990 is an excellent collection of articles. Perkin, H., The Rise of Professional Society: England since 1880, (Routledge), 1989 extends his earlier work in a masterful study. Meacham, Stanish, A Life Apart: The English Working-class 1890-1914, (Thames & Hudson), 1977 and Bourne, Joanna, Working-class Cultures in Britain 1890-1960, (Routledge), 1994 are excellent.

[4] See Disraeli, Benjamin, Sybil or The two nations, (B. Tauchnitz), 1845.

[5] Gaskell, Elizabeth, North and South, (B. Tauchnitz), 1855, p. 48.

[6] Ibid, Thompson, E.P., The Making of the English Working-class.

[7] Foster. J., Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution: early industrial capitalism in three English towns, (Weidenfeld), 1974.

[8] Foster’s view of the petit bourgeoisie and his attempts to explain it away have been criticised by historians such as R.S. Neale who interpose a ‘middling’ class between the middle and working-classes in his ‘five-class model’: Neale, R.S., ‘Class and class-consciousness in early 19th century England: three classes or five?’, Victorian Studies, Vol. 12, (1968-9), pp. 5-32.

[9] Ibid, Foster. J., Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution: early industrial capitalism in three English towns, pp. 47-72.

[10] Ibid, Foster. J., Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution: early industrial capitalism in three English towns, pp. 73-125.

[11] Ibid, Foster. J., Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution: early industrial capitalism in three English towns, pp. 203-249.