Literacy is difficult to define with any degree of accuracy and, in the first sixty years of the nineteenth century difficult to quantify.[1] The concept of literacy can be defined very broadly as a person’s ability to read and sometimes write down the cultural symbols of a society or social group. [2] Literacy has always been a two-edged sword providing the means to expand experience but also leading to control over what people read. It is not surprising that the dominant culture wants to control literacy while subordinate groups call for freer access to the ‘really useful knowledge’ of the dominant culture.[3]

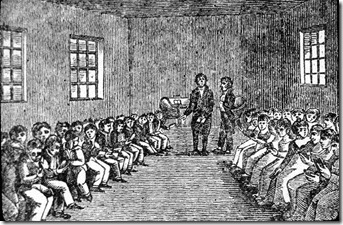

The economic innovations of the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries led to important changes in the working life of many people who were increasingly drawn to work in factories. This disrupted earlier patterns of domestic and community life. Child employment meant that many children were denied the disciplines of schooling. New types of schools were established to compensate for these factory-related developments. Factory schools, Sunday schools, evening schools and infant schools were all designed to accommodate the consequences of industrialisation. These new schools adopted a new social agenda seeking not only to inculcate virtue but also remould their pupils to fit in with the needs of an industrial society. Schools began to place much greater emphasis on continuous and regular attendance with teachers developing elaborate pedagogies to ensure that all children remained busy at their allotted tasks.

Two developments flowed from this. First, much greater attention was given to the education, training and competence of elementary school teachers. Rote methods were given much less attention and, instead, teachers were expected to be accomplished in more intellectual methods of instruction. They were expected not merely to inspect the contents of their pupils’ minds by hearing memorised lessons but also to exercise the minds of their charges by questioning them on their lessons. Secondly, there was a major expansion of the school curriculum promoted alongside the spread of elementary education. Children began to be taught through secular as well as religious topics. It was assumed that if children knew how the world worked, they would be more ready to accept their allotted, if unnatural, place in the scheme of things. Another educational consequence of economic change was that writing began to enter the core curriculum of schooling. This did not meet with unqualified approval. Some argued that writing, a business skill, should not be taught in Sunday schools, while others claimed that it would promote crime; ‘if you teach them to write, you teach them to forge’. Many assumed that writing skills would elevate people above their proper station in life. Nevertheless, there was a powerful lobby that recognised the importance of writing skills to the prosperity and administration of the economy. The army of clerks expanded with industrialisation.

The spread of reading skills was aided by the technology of printing in the 1830s and 1840s with the steam-driven printing press. The spread of writing in commercial institutions also received a technological stimulus with the invention of the mass-produced and low-cost steel-nibbed pen in the 1830s and the introduction of cheaper esparto grass paper in the 1860s to replace the expensive quills, penknives and paper. The stamp duty on newspapers and the tax on paper were both substantially reduced in 1836 and finally abolished in 1855 and 1861 respectively. The average price of books halved between 1828 and 1853. Books and newspapers became more readily available with the Public Libraries Act of 1850 and communications were improved by the introduction of the Penny Post in 1840.[4]

‘Read or was read to’: it is only in the course of the nineteenth century that reading gradually became a private rather than a public act for the mass of the population. Until the 1830s, if you could read, you were expected to read aloud and share your reading with family, friends and workmates.[5] A population with a significant proportion of ‘illiterates’ may not be ill-informed and may be at least as well informed as a population where the formal reading skill is widely diffused but seldom used.

There is some debate over whether levels of literacy were rising or falling in the first thirty years of the nineteenth century. The problem that historians face is that there is no agreed standard for measuring literacy in this period. Attempts have taken two main forms: a counting of institutions and a counting of signatures on marriage registers and legal documents. Both are fraught with problems. Counting the number of schools tells historians little about the education that went on in them, the average attendance, length of the school year or average length of school life, all of which have a direct relevance to levels of literacy. Counting signatures likewise poses problems. It may lead to an overestimation of literacy levels as individuals may be able to sign but have little else in the way of literacy skills. Conversely, the same evidence may lead to an underestimation of literacy skills. Writing requires a productive proficiency that reading does not and those who cannot sign may be able to read, but would be in danger of being classified as illiterate. Yet signatures are the better figures, far more soundly based than attempts to count schools or scholars.

W.P. Baker’s survey of seventeen country parishes in the East Riding of Yorkshire found that male literacy was 64% in both 1754-1760 and 1801-1810 and rose steadily afterwards.[6] Lawrence Stone argues that literacy was rising between the 1770s and 1830 based upon more widespread analysis seeing this as a result of the process of industrialisation and its demands for a more literate workforce.[7] This optimistic view has, however, been called into question as far as England as a whole was concerned. There are various reasons for questioning whether literacy did rise. First, the sharp rise in population after the 1760s began to swamp the existing provision of schools, especially charity schools funded by local patrons.[8] Private, charitable investment in education slackened after 1780 as people diverted their investment into more expensive and pressing outlets such as enclosure, canal and turnpike investment. The dynamic areas of growth in the education system were no longer the charity schools for the working population but private fee-paying schools for the upper-classes and grammar schools for the middle-classes. Secondly, children were drawn into the new processes of industrialisation and there were increased opportunities to employ them from an early age. This too militated against working-class children receiving an education that would make and keep them literate, especially in industrial areas.[9] Under these circumstances it would not be surprising if literacy rates did sag. There is some statistical evidence for a fall in literacy in the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth. Studies of Lancashire, Devon and Yorkshire suggest that there was a sharp fall in literacy in the 1810s and 1820s from around 67% to fewer than 50%. Stephen Nicholas has examined 80,000 convicts transported to Australia between 1788 and 1840 and he found that urban literacy continued to rise until 1808 and rural literacy to 1817 but then both fell consistently for the rest of the period.[10]

It was the Sunday school movement that from the 1780s countered these factors. In 1801, there were some 2,290 schools rising to 23,135 in 1851 with over 2 million enrolled children. By then, three-quarters of working-class children aged 5-15 were attending such institutions. However, there are some limitations to making a strong case that Sunday schools sustained the literacy rate. First, many schools ceased the teaching of writing after the 1790s. Secondly, they have been seen as either the creation of a working-class culture of respectability and self-reliance or as middle-class conservative institutions for the reform of their working-class pupils from above. A positive force in a worsening situation, they probably prevented literacy falling more than it did in areas vulnerable to decline. These divergent views illustrate the difficulty of extrapolating from specific examples to a general picture. ‘England’, especially urban England, was not a homogenous unit experiencing ‘optimistic’ or ‘pessimistic’ literacy trends before 1830.

From 1830, levels of literacy began to rise, a process that continued for the rest of the century, though inevitably with regional variation in pace. Literacy rates were published by the Registrar General for each census year in percentages.

|

| 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 |

| Male | 67.3 | 69.3 | 75.4 | 80.6 |

| Female | 51.1 | 54.8 | 65.3 | 73.2 |

This was paralleled by growth in the average number of years of schooling for boys: 2.3 years in 1805 to 5 years in 1846-1851 to 6.6 years by 1867-1871. Various factors lay behind this, but first it is important to consider the motives both of educators and of educated that made this possible. The Churches were concerned with the salvation of souls and the winning back of the irreligious working-class urban population to Christianity. The Church of England felt itself under attack from a revival of Nonconformity and Catholicism in the 1830s. By 1870, there were 8,798 voluntary assisted schools of which 6,724 were National Society Schools. At a more secular level the long period of radical unrest from the 1790s to the 1840s created deep anxiety about order and social control. Richard Johnson put it well when he says

The early Victorian obsession with the education of the poor is best understood as a concern about authority, about power, about the assertion (or the reasserting) of control.[11]

For example, in Spitalfields much education was aimed at controlling the population in the interests of social and economic stability while in the north-eastern coalfields coal owners created schools attached to collieries in the 1850s as a means of social control following damaging strikes in 1844.[12]

The social control argument dated back to the Sunday Schools, the SPCK Charity schools and beyond. These suggested that schooling and literacy would make the poor unfit for the performance of menial tasks because it would raise their expectations. Even worse, the acquisition of literate skills would make the working-classes receptive to radical and subversive literature. This was the essential dilemma: whether to deny education to the poor and so avoid trouble, or whether to provide ample education in the hope that it would serve as an agent of social control. By the late 1830s, the latter ideology dominated the minds of policy makers. First, education was seen as a means of reducing crime and the rising cost of punishment. Secondly, it was seen as a way of keeping the child or the child when adult out of the workhouse. In the 1860s, these views were joined by two other that presaged the 1870 Act. The military victories of Prussia and the northern States of America in the 1860s suggested that good levels of education contributed to military efficiency. At home the Reform Act 1867 prompted concern to ensure the education of those who would soon wield political power through an extended franchise: ‘we must now education our masters’ spoke Robert Lowe, a leading Conservative politician. Education may have been of limited value for actual performance in some occupations, but it had important wider bearings on the creation of an industrial society. It made it possible for people to be in touch with a basic network of information dispersal and could make labourers aware of the possibilities open to them or the products of consumers. For such reasons, a positive belief in the value of education on the part of the authorities replaced earlier assumptions that teaching the poor to read would merely lead to the diffusion of subversive literature and the wholesale flight of the newly educated from menial tasks.

The literacy rate was driven up by the injection of public money into the building and maintenance of elementary schools. This rose from £193,000 in 1850 to £723,000 in 1860 and £895,000 by 1870. The money was channelled largely into two religious societies: the Anglican National Society, founded in 1811, and the British and Foreign School Society, a Nonconformist body created three years later. These bodies raised money to build schools usually run on monitorial lines. However, by the early 1830s, it was obvious that they were unable to counter the defects in school provision, especially in the north. State funding began in 1833 with investment of about 1% of national income. From the 1840s, under the guidance of the Privy Council for Education and its Secretary James Kay-Shuttleworth, expenditure increased as grants were extended from limited capital grants for buildings to equipment in 1843, teacher training three years later and capitation grants for the actual running of schools in 1853. Closer control over these grants was instituted in 1862 with the system of payment by results and by a reduction of teacher training to try and control sharply rising expenditure.

Important though the role of the state and religious societies was in developing literacy levels, some historians have pointed to the large sector of cheap private education where the working-classes bought education for their children outside the church and state system. It has been suggested that at least a quarter of working-class children were educated in this way. Many in the working-class spurned the new National and British schools and chose slightly more expensive, small dame and common day schools. Although their quality was maligned by publicists such as Kay-Shuttleworth who advocated a state-financed system, they were not regarded as part of the authority system and had no taint of charity or the heavy social control of the Churches. Parents often regarded the teachers as their employees and they fitted in with working-class lifestyles.[13]

There is no doubt, however, that the expansion of this type of education did result in the creation of a remarkably literate working-class. A major factor in rising literacy was the creation of a teaching profession in elementary schools. The religious societies had their own training colleges before the 1830s and from 1839 many Anglican dioceses established colleges to serve diocesan National Schools. The system received its most important stimulus from the Minutes of 1846 that established the training and career structure for teachers. The 1850s saw the rapid rise of a schoolteacher class: there were 681 certificated teachers in 1849 but 6,878 ten years later. A further important factor was the role of Her Majesty’s Inspectors first appointed in 1839 to ensure that the state grant was spent properly. Their duties expanded into more educational roles, examining pupil teachers and the training colleges, calculating the capitation grants of the 1850s and then examining children in the subjects on which the grant was based in the 1860s. They encouraged the replacement of the monitorial system with class teaching. By 1870, their number has risen from 2 to 73.

Four things mopped up the illiteracy of deprived groups who, left to themselves, would have remained a hard core of illiterates: the ragged, workhouse, prison and factory schools. Ragged schools began during the early 1840s and the Ragged School Union dated from 1844. They charged no fees and took the poorest children for a basic education, depending for their support on a circle of philanthropists including Charles Dickens. By 1852, there were 132 Ragged Schools in London with 26,000 children and 70 outside the capital in 42 towns. By 1870, at their peak, there were 250 schools in London and 100 in the provinces until they were taken over by the School Boards.

Workhouse and prison schools catered for children who had lost their freedom or who had fallen into the safety-net of the workhouse. Their education was guaranteed in the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act and the 1823 Prisons Act. Finally, factory schools were created by the 1833 Factory Act that obliged factory owners to ensure that their child workers received a regular education either in a factory schools or outside before being allowed to work. This was firmly enforced. All these measures helped the most disadvantaged groups of children.

Mass elementary education was grounded in the basic skills of reading, writing and arithmetic. Religion and bible study was equally central to the religious societies. Attempts to extend the curriculum were stopped when the Revised Code limited grants to the 3Rs and away from the broader cultural subjects. From 1867, history, geography and geometry were made grant-earning subjects but languages and a range of science subjects had to wait until the 1870s. What was learned was important and the development of a body of reading material accessible to the masses was a characteristic feature of the years after 1830.

At the school level, the SPCK, acting as the publishing arm of the National Society, set up its Committee of General Literature and Education in 1832 to produce schoolbooks.[14] The National Society gradually took over from the SPCK and in 1845 established its own book collection for National schools. The British Society similarly published secular books for schools after 1839. There was also concern among the governing elite to provide informative books for adults that would divert them away from the propaganda of radicalism. The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, established in 1826, issued a library of cheap, short books on popular science, history and all types of secular subjects to combat the strong tradition of radical literature ushering in publishing for a mass audience.[15] The Society was particularly influential in spreading science to a broad and diverse population. It was deliberately inclusive in its audience, actively seeking to make its publications useful and appealing to a wide variety of readers of all classes, genders, educational levels and professions. By providing the same information, in the same format, for all readers, the Society democratised learning across the social boundaries of the period and broadened the horizon for future popularisers. The commercial market also played an increasingly important role for literate society with the sensationalist ‘penny dreadfuls’, serialisation of novels by authors such as Dickens, Gothic and romantic novels and the railway reading of W.H. Smith.

Literacy rates had risen by the 1860s before the advent of state secular schools or free or compulsory education. However, one and a half million children, 39% of those between 3 and 12 were not at school and there was a further million children without school places even had they chosen to attend. The 1870 Act filled in the gaps in areas where voluntary provision was inadequate. The building of non-sectarian schools, the work of 2,000 School Boards and compulsory education after 1880 finally led to the achievement of mass literacy by 1900.

[1] On literacy see Cipolla, C.M., Literacy and the Development in the West, (Penguin), 1969 contains an excellent chapter on literacy and the industrial revolution. Altick, R.D., The English Common Reader, (Phoenix Books), 1963, Webb, R.K., The British Working-class Reader 1790-1848: Literacy and Social Tension, (Allen & Unwin), 1955 and Sanderson, M., Education, Economic Change and Society in England 1780-1870, 2nd ed., (Macmillan), 1991 contain important material. Vincent, D., Literacy and popular culture: England 1750-1914, (Cambridge University Press), 1989 is an important study based on computerised research. Smith, O., The Politics of Language 1791-1819, (Oxford University Press), 1984 examines how ideas about language were used to maintain repression and class divisions.

[2] The concept of functional literacy has been developed to deal with the semantic problem of defining ‘literacy’. It was originally coined by the United States Army during World War II and denoted an ability to understand military operations and to be able to read at a fifth-grade level. Subsequently, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defined functional literacy in terms of an individual possessing the requisite reading and writing skills to be able to take part in the activities that are a normal part of that individual’s social milieu.

[3] On ‘useful knowledge’, see Connell, Philip, Romanticism, Economics and the Question of ‘Culture’, (Oxford University Press), 2001, pp. 76-83.

[4] On popular literature Williams, R., The Long Revolution, (Penguin), 1961 contains important chapters on the growth of the reading public and the popular press. Ibid, Vincent, D., Literacy and popular culture: England 1750-1914 and Neuburg, V.E., Popular Literature: A History and Guide, (Penguin), 1977 are good introductions. James, L., Print and the People 1819-1851, (Peregrine), 1978 and Fiction for the Working Man 1830-1850, (Penguin), 1973 are more detailed studies. Cross, N., The Common Writer: Life in nineteenth century Grub Street, (Cambridge University Press), 1985 is the most useful study of nineteenth century writing. On the press Read, D., Press and People 1790-1850: Opinion in Three English Cities, (Edward Arnold), 1961 is excellent on the impact of the middle class press while Hollis, P., The Pauper Press: A Study in Working-Class Radicalism of the 1830s, (Oxford University Press), 1970, Wickwar, W.H., The Struggle for the Freedom of the Press 1819-1832, (Allen & Unwin), 1928 and Weiner, J., The War of the Unstamped: the movement to repeal the British newspaper tax, 1830-1836, (Cornell University Press), 1969 on the popular press. There has been a proliferation of regional and local studies on the role of the press: for example, Milne, M., Newspapers of Northumberland and Durham, (Graham), 1951 and Murphy, M.J., Cambridge Newspapers and Opinion 1780-1850, (Oleander Press), 1977. Shattock, J. and Wolff, M., (eds.), The Victorian Periodical Press: Samplings and Soundings, (Leicester University Press), 1982 contains several valuable articles. Koss, Stephen, The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain, (Fontana), 1990 is a monumental study.

[5] Vincent, D., ‘The decline of oral tradition in popular culture’, in Storch R.D., (ed.), Popular culture and custom in 19th-century England, (Croom Helm), 1982, pp. 20-47.

[6] Baker, W.P., Parish registers and illiteracy in East Yorkshire, (East Yorkshire Local History Society), 1961

[7] Stone, L., ‘Literacy and education in England 1640-1900’, Past and Present, Vol. 42, (1969), pp. 69-139.

[8] Jones, Mary, The Charity School Movement: A Study of Eighteenth Century Puritanism in action, (Cambridge University Press), 1938 and Mason, J., ‘Scottish Charity Schools of the Eighteenth Century’, Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 33, (1), (1954), pp. 1-13.

[9] Sanderson, M., ‘Literacy and social mobility in the industrial revolution in England’, Past and Present, Vol. 56, (1972), pp. 75-104.

[10] Nicholas, Stephen, (ed.), Convict Workers: Reinterpreting Australia’s Past, (Cambridge University Press), 1988; see also, Richards, E., ‘An Australian map of British and Irish literacy in 1841’, Population Studies, Vol. 53, (1999), pp. 345-359.

[11] Johnson, Richard, ‘Educational Policy and social control in early Victorian England’, Past & Present, Vol. 49, (1970), p. 119.

[12] McCann, Phillip and Young, Francis A., Samuel Wilderspin and the Infant School Movement, (Taylor & Francis), 1982, pp. 15-33 and McCann, Phillip, ‘Popular Education, Socialisation and Social Control: Spitalfields 1812-1824’, in McCann, Phillip, (ed.), Popular Education and Socialisation in the Nineteenth Century, (Methuen), 1977, pp. 1-49 consider Spitalfields. Colls, R., ‘‘Oh Happy English Children!’: Coal, Class and Education in the North-East’, Past & Present, Vol. 73, (1), pp. 75-99 looks at coalfield schools.

[13] Gardner, Philip, ‘Literacy, Learning and Education’, in Williams, Chris (ed.), A companion to nineteenth-century Britain (Blackwell Publishers), 2004, pp. 353-368.

[14] Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, the oldest Anglican mission organisation was founded in 1698 in England to encourage Christian education and the production and 1709 in Scotland as a separate organisation for establishing new schools. See, Allen, William Osborne Bird and McClure, Edmund, Two Hundred Years: the History of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1698-1898, (SPCK), 1898 and Clarke, W.K.L., A History of the SPCK, (SPCK), 1959.

[15] Kinraid, R.B., The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and the democratization of learning in early nineteenth-century Britain, (University of Wisconsin-Madison), 2006. See also, Rauch, Alan, Useful Knowledge: the Victorians, morality, and the march of intellect, (Duke University Press), 2001,