When the Act that had extended the life of the Poor Law Commission ran out in 1847 it was not renewed and the Poor Law Board Act was passed in its place. It set up a new body, the Poor Law Board, consisting in theory of four senior ministers (the Home Secretary, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord President of the Council and the Lord Privy Seal). In practice, like the Board of Trade, it was a mere fiction and never intended to meet. The real power lay with its President, who was eligible to sit in Parliament, and his two Secretaries, one of whom could become an MP. It was expected that the President would sit in the House of Lords and the Permanent Secretary in the Commons but in practice both ministers were usually MPs. The 1847 Act had two great merits. It remedied the weakness caused by the old board’s independent status: the government was now genuinely responsible and there was a proper channel between the board and parliament. It stilled the long agitation against the new poor law and meant that the new board could undertake a common-sense policy of gradual improvement in peace. It was aided in this by the improved economic situation and by the fact that the laws of settlement were also swept away in 1847.

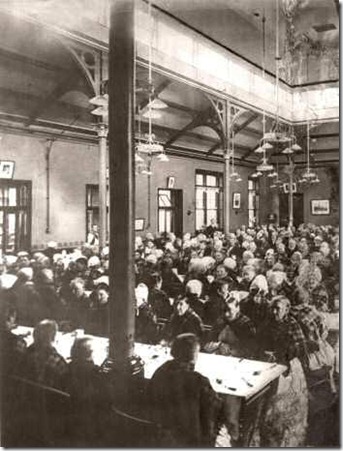

Workhouse women, Leeds c1900

The achievements of the board between 1847 and 1870 were limited but a beginning was made in several fields. In 1848, the first schools for pauper children were set up and these were extended by legislation in 1862; in the 1850s outdoor relief was frankly admitted and regulated; by 1860, segregation of different classes of pauper into different quarters of the workhouse was virtually accomplished and the harshness of the old uniform regulations was softened. Even by the 1870s, the workhouse was still barbarous in many places and as a system but important changes had taken place. More and more money was being spent on the poor and unfortunate without protest. Pauperdom, especially for the able-bodied poor, was being increasingly regarded as misfortune rather than a crime or cause for segregation. The stigma of disfranchisement was not removed until 1885.

By the 1860s, the Poor law service had moved away from controversy and into a phase of consolidation. The administration became less centralised, less doctrinaire and to some extent less harsh. Inspectors turned to advising on workhouse management rather than applying blind deterrent policies. The cost per capita for 1864-1868, for example, was the same as it had been twenty years earlier and was one third cheaper than forty years earlier. Boards of Guardians had more freedom to respond to local conditions and outdoor relief was given more frequently. The Lancashire cotton famine of the early 1860s brought matters to a head.[1] The action that sparked depression overseas was the blockade of the southern American ports by Federal Navy. This cut off the supply of raw cotton to Europe, including Lancashire and Scotland. At the start of this depression, Lancashire mills had four month supply of cotton stockpiled. The impact did not hit immediately and they had enough time to stockpile another month.[2] Without raw further materials, production had stopped by October 1861 and mill closures, mass unemployment and poverty struck northern Britain leading to soup kitchens being opened in early 1862. Relief was provided by the British government in the form of tokens that were handed to traders so that goods could be exchanged to that amount. [3] Emigration to America was offered as an alternative; agents came to recruit for the American cotton industry and also for the Federal army. Workers also made the shorter move to Yorkshire for work in the woollen mills there. Blackburn alone lost approximately 4,000 workers and their families. On 31 December 1862, cotton workers met in Manchester and decided to support those against slavery, despite their own impoverishment.

The workers felt bitter at the nominal relief provided by the government and also resented that other relief came from affluent donors from outside Lancashire, not from their own wealthy cotton masters. It was also felt that no distinction was made between those who were previously hard working and forced into unemployment and those who were ‘stondin paupers’ or drunkards.

This built up bitterness and resentment that led to rioting especially in Stalybridge, Dukinfield and Ashton in 1863. Poor law and charity solutions proved inadequate and government, both central and local, thought that it was justifiable to intervene to create employment. As a result, government relief was changed and instead provided in the form of constructive employment in urban regeneration schemes, implemented by local government.

The Public Works (Manufacturing Districts) Act 1863 gave powers to local authorities to obtain cheap loans to finance local improvements. This Act, as much as anything, symbolised the failure of the nineteenth century poor law to cope with the problem of large-scale industrial unemployment. Poor law financing was changed in the Union Chargeability Act 1865 ending the system where each union was separately responsible for the cost of maintaining its own poor. Each parish now contributed to the union fund with charges based upon the rateable value of properties. This led to inequalities since the rateable value of houses was set locally across the country and, in many areas, boards of guardians, themselves often middle-class ratepayers kept rates as low as possible. The Metropolitan Poor Act 1867 spread the cost of poor relief across all London parishes and provided for administration of infirmaries separate from workhouses. [4] Lunatics, fever and smallpox cases were removed from management of the Guardians and a new authority, the Metropolitan Asylums Board provided hospitals for them.[5]

In 1871, the Local Government Act set up a new form of central administration, the Local Government Board combining the work of the Poor Law Board, the Medical Department of the Privy Council and a small Local Government section of the Home Office. There were attempts by the Local Government Board and its inspectorate during the next decade to reduce the amount of outdoor relief by urging boards of guardians to enforce the regulations restricting outdoor relief more stringently and supported those boards that took a strict line. This meant that using the poor law system as a device to cope with unemployment more difficult and led to the unemployed seeking relief from other sources. This trend was given official recognition in 1886 when Joseph Chamberlain, the President of the Local Government Board, issued a Circular that urged local authorities to undertake public works as a means of relieving unemployment.[6]

These measures did not reduce the proportion of paupers receiving relief outside the workhouse but they did reduce the number of paupers: in 1870, paupers made up 4.6% of the population of England and Wales but by 1900, this had fallen to 2.5%. The poor law system of the late nineteenth century was gradually moving towards greater specialisation in the treatment of those committed to its care. This can be seen in the increase in expenditure on indoor relief by 113% between 1871-1872 and 1905-1906, though the number of indoor paupers only increased by 76%. In the conditions of the late-nineteenth century the focus shifted from pauperism to an increasing awareness of poverty and to the growing demand for an attack on it. While the Boards of Guardians retained control over paupers, other agencies became more important in dealing with various kinds of poverty.

School boards from 1870 and local education authorities after 1902 played a vital role in exposing and dealing with child poverty. School feeding and medical inspections developed out of the work of these bodies not out of the poor law system. At the other end of the age spectrum, opinion was moving in favour of old-age pensions in some form to take the poor out of the sphere of the poor law. A Royal Commission on the Aged Poor that reported in 1895 favoured the improvement of poor law provisions for old people but rejected the pension idea. Four years later, however, a Parliamentary Select Committee on the Aged Deserving Poor reported in favour of pensions. The policy of the Chamberlain Circular of providing work for the unemployed was continued both by local authority and by some philanthropic bodies such as the Salvation Army. In 1904, with unemployment worsening, the Local Government Board encouraged the creation of joint distress committees in London to plan and co-ordinate schemes of work relief for the unemployed. The Unemployed Workmen Act 1905 made the establishment of similar distress committees in every large urban area in the country mandatory. The committees were also empowered to establish labour exchanges, keep unemployment registers and assist the migration or emigration of unemployed workmen. This Act, it has been maintained, marked the culmination of attempts to deal with unemployment through work relief schemes. [7]

Poor relief costs rose to £8.6 million by 1906 and poor economic conditions in 1902 and 1903 had seen the numbers seeking relief rise to two million people. The result was the establishment in August 1905 of a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and the Relief of Distress by the outgoing Conservative government chaired by Lord George Hamilton. The commission included Poor Law guardians, members of the Charity Organisation Society[8], members of local government boards as well as the social researchers Charles Booth and Beatrice Webb. The Commission spent four years investigating and in February 1909 produced two conflicting reports known as the Majority Report and the Minority Report. The Majority Report reiterated that poverty was largely caused by moral issues and that the existing provision should remain. However, it believed that the Boards of Guardians provided too much outdoor relief and that the able-bodied poor were not deterred from seeking relief because of mixed workhouses. The Minority Report took a different stance arguing that what was needed was a system radically different from current provision by breaking up the Poor Law into specialist bodies dealing with sickness, old-age etc administered by committees of the elected local authorities. It also recommended that unemployment was such a major problem that it was beyond the scope of local authorities and should be the responsibility of central government. However, because of the differences between the two reports, the Liberal government was able to ignore both when implementing its own reform package.

[1] Arnold, R. A., Sir, The history of the cotton famine: from the fall of Sumter to the passing of the Public Works Act, (Saunders, Otley and Co.), 1864, Henderson, W.O., The Lancashire cotton famine, 1861-1865, (Manchester University Press), 1934 and Farnie, Douglas A., ‘The cotton famine in Great Britain’, in Ratcliffe, B.M., (ed.), Great Britain and her world 1750-1914: essays in honour of W.O. Henderson, (Manchester University Press), 1975, pp. 153-178.

[2] For the impact of the famine see, Holcroft, Fred, The Lancashire cotton famine around Leigh, (Leigh Local History Society), 2003, Peters, Lorraine, ‘Paisley and the cotton famine of 1862-1863’, Scottish Economic & Social History, Vol. 21, (2001), pp. 121-139, Henderson, W.O., ‘The cotton famine in Scotland and the relief of distress, 1862-64’, Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 30, (1951), pp. 154-164 and Hall, Rosalind, ‘A poor cotton weyver: poverty and the cotton famine in Clitheroe’, Social History, Vol. 28, (2003), pp. 227-250

[3] Shapely, Peter, ‘Urban charity, class relations and social cohesion: charitable responses to the Cotton Famine’, Urban History, Vol. 28, (2001), pp. 46-64, Boyer, George R., ‘Poor relief, informal assistance, and short time during the Lancashire cotton famine’, Explorations in Economic History, Vol. 34, (1997), pp. 56-76 and Penny, Keith, ‘Australian relief for the Lancashire victims of the cotton famine, 1862-3’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, Vol. 108, (1957 for 1956), pp. 129-139.

[4] Ashbridge, Pauline, ‘Paying for the poor: a middle-class metropolitan movement for rate equalisation, 1857-67’, London Journal, Vol. 22, (1997), 107-122.

[5] Powell, Allan, Sir, The Metropolitan Asylums Board and its work, 1867-1930, (The Board), 1930 and Ayers, G.M., England’s first state hospitals and the Metropolitan Asylums Board, 1867-1930, (Wellcome Institute), 1971.

[6] Hennock, E.P., ‘Poverty and social theory: the experience of the 1880s’, Social History, Vol. 1, (1976), pp. 67-91.

[7] Harris, J., Unemployment and Politics, 1886-1914, (Oxford University Press), 1972 and Melling, J., ‘Welfare capitalism and the origin of welfare states: British industry, workplace welfare, and social reform, 1870-1914’, Social History, Vol. 17 (1992), pp. 453-478.

[8] Vincent, A.W., ‘The poor law reports of 1909 and the social theory of the Charity Organisation Society’, in Gladstone, David, (ed.), Before Beveridge: welfare before the welfare state, (Institute of Economic Affairs Health and Welfare Unit), 1999, pp. 64-85.