Between 1830 and 1914, there were two period when state intervention in British social policy significantly increased. The first of these was in the 1830s and 1840s and the second in the Edwardian years at the beginning of the twentieth century. Fundamental in the first burst of reforming activity was the New Poor Law of 1834, which centred round the workhouse system. It gave conditional welfare for a minority, with public assistance at the price of social stigma and loss of voting rights.

Some Edwardian reforms still retained conditions on take-up, as in the first old-age pensions in 1908, where tests of means and character eligibility were reminiscent of the Poor Law. Three years later, in 1911, there was a radical departure in the national scheme for insurance against ill-health and unemployment that conferred benefits as a result of contributions. It was still a selective scheme, limited to a section of the male population and entirely left out dependent women and children.

The nineteenth century had inherited the attitude that such a state of affairs was both right and proper. Many contemporary writers regarded poverty as a necessary element in society, since only by feeling its pinch could the labouring poor be inspired to work. Thus it was not poverty by pauperism or destitution that was regarded as a social problem. [1] Many early Victorians adopted the attitude that combined fatalism, ‘For ye have the poor always with you’[2] and moralism, destitution was the result of individual weakness of character. Fraser’s Magazine in 1849 commented that

So far from rags and filth being the indications of poverty, they are in the large majority of cases, signs of gin drinking, carelessness and recklessness.[3]

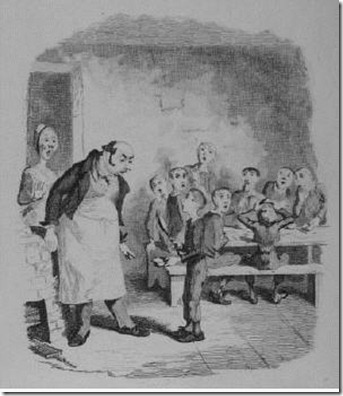

Such cases if congregated together in sufficient numbers seemed to constitute a social menace.[4] It was thinking of this sort that provided the impetus to poor law reform in 1834. Relief continued to be offered but only in the workhouse where the paupers would be regulated and made less comfortable than those who chose to stay outside and fend for themselves, the principle of ‘less-eligibility’. Those who were genuinely in dire need would accept the workhouse rather than starve. Those who were not would prefer to remain independent and thus avoid the morally wasting disease of pauperism. The Poor Law of 1834 provided an important administrative model for future generations with central policy-making and supervision and local administration but the workings of this model were often profoundly disappointing to the advocates of ‘less-eligibility’ as a final solution to the problem of pauperism. But the issue was not pauperism, the issue on which contemporaries focused, but the debilitating effects of poverty itself.

Poverty is a term that is notoriously difficult to define. In simple terms, the failure to provide the basic necessities of life, food, clothes and shelter results in a state of poverty.[5] British society in the nineteenth century was poor by modern standards. The net national income per head at 1900 prices has been estimated as £18 in 1855 and £42 in 1900. Even the higher paid artisan might find himself at a time of depression unable to get work even if willing and anxious to do so. Most members of the working-class experienced poverty at some time in their lives and, compared to the middle-classes, their experience of poverty was likely to be a far more frequent, if not permanent one.

It was not until near the end of the nineteenth century that poverty was first measured in any systematic fashion and most of the evidence of the extent and causes of poverty is from around 1900.[6] The number of paupers had long been known: they amounted to about 9% of the population in the 1830s and this fell to less than 3% by 1900. Far more suffered from poverty than ever applied for workhouse relief. In 1883, Andrew Mearns in his Bitter Cry of Outcast London claimed than as much as a quarter of the population of London received insufficient income to maintain physical health.[7] Impressionistic claims like this led Charles Booth to begin his scientific investigation of the London poor in 1886. He found that as much as 30% of the population of London and 38% of the working-class lived below the poverty line.[8]

Booth‘s conclusions were criticised by some who pointed to the unique position of London. However, B. Seebohm Rowntree[9] did a similar survey of his native York and in 1899 published conclusions that mirrored those of Booth. [10] He distinguished between ‘primary poverty’ and ‘secondary poverty‘.[11] Primary poverty was a condition where income was insufficient even if every penny was spent wisely. Secondary poverty occurred when those whose incomes were theoretically sufficient to maintain physical efficiency suffered poverty as a consequence of ‘insufficient spending’. 10% of York’s population and 15% of its working-classes were found to be in primary poverty. A further 18% of the whole population and 28% of the working-classes were living in secondary poverty. Rowntree also emphasised the changing incidence of poverty at different stages of working-class life, the ‘poverty cycle’ with its alternating periods of want and comparative plenty.[12]

Other surveys followed the work of Booth and Rowntree.[13] The most notable was the investigation in 1912-1913 of poverty in Stanley (County Durham), Northampton, Warrington and Reading by A.L. Bowley and A.R. Burnett-Hurst.[14] They found that the levels of poverty reflected different economic conditions and that among the working-class population primary poverty accounted for 6%, 9%, 15% and 29% in the respective towns. These conclusions questioned the assumption made by both Booth and Rowntree that similar levels of poverty might be found in most British towns. In fact, the diversity of labour market conditions was reflected in considerable variation in the levels and causes of poverty.

It is important to examine the reliance that can be placed on the results of early poverty surveys as few of their results can be accepted with complete confidence. Booth relied heavily on data from school attendance officers and families with children of school age, itself a cause of poverty were over-represented in what he supposed to be a cross section of the population. Rowntree‘s estimates of food requirements were later regarded as over-generous by nutritionists and he later conceded after a second survey in 1936 that his 1899 poverty lines were ‘too rough to give reliable results’.[15] Working-class respondents, confronted by middle-class investigators were notoriously liable to underestimate income. Most poor law and charity assistance was means tested and the poorer respondents, suspecting that investigators might have some influence in the disposal of relief, took steps not to jeopardise this. Income acquired illegally was likely to remain hidden. It is difficult to compare these levels with poverty at other times. Recent attempts by historians to assess approximate numbers that lived below Rowntree‘s poverty line in mid-nineteenth century Preston, York and Oldham all suggest poverty levels higher than those at the time of the 1899 survey. This is not surprising as between 1850 and 1900 money wages rose considerably and many more insured themselves against sickness and other contingencies.

[1] A ‘pauper’ can simply be defined as an individual who was in receipt of benefits from the state. A labourer who was out of work was termed an able-bodied pauper, whereas the sick and elderly were called impotent paupers. Relief was given in a variety of ways. Outdoor relief was when the poor received help either in money or in kind. Indoor relief was when the poor entered a workhouse or house of correction to receive help. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 said that paupers should all receive indoor relief.

[2] St Matthew, 26: 8-11.

[3] ‘Work and Wages’, Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, Vol. xl, (1849), p. 528.

[4] It is important to remember the ‘revolutionary psychosis’ that afflicted many within the ruling elite during the first half of the nineteenth century. Poverty was seen in this revolutionary light.

[5] On this subject the briefest introduction is Rose, M.E., The Relief of Poverty 1834-1914, (Macmillan), 2nd ed., 1986.

[6] Englander, David and O’Day, Rosemary, (eds.), Retrieved Riches: Social Investigation in Britain, 1840-1914, (Scolar Press), 1995 examines the nature of social investigation.

[7] Ibid, Mearns, Andrew, The Bitter Cry of Outcast London: An Inquiry into the Condition of the Abject Poor, pp. 15-18.

[8] Booth, Charles, Life and Labour of the People in London, 17 Vols. (Macmillan), 1889-1903. Norman-Butler, Belinda, Victorian Aspirations: the Life and Labour of Charles and Mary Booth, (Allen and Unwin), 1972 and Simey, T.S. and M.B., Charles Booth: Social Scientist, (Liverpool University Press), 1960 are sound biographies and Fried, A. and Elman, R., (eds.), Charles Booth’s London: a Portrait of the Poor at the Turn of the Century. Drawn from His ‘Life and Labour of the People in London’, (Harmondsworth), 1969 a useful collection of sources. O’Day, Rosemary and Englander, David, Mr Charles Booth’s Inquiry: Life and Labour of the People in London Reconsidered, (Hambledon), 1993, Gillie, Alan, ‘Identifying the poor in the 1870s and 1880s’, Economic History Review, Vol. 61, (2008), pp. 302-325 and Spicker, P., ‘Charles Booth: the examination of poverty’, Social Policy and Administration, Vol. 24, (1990), pp. 21-38 examine Booth’s ideas. .

[9] On Rowntree see, Bradshaw, Jonathan and Sainsbury, Roy, (eds.), Getting the measure of poverty: the early legacy of Seebohm Rowntree, (Ashgate), 2000 and Briggs, Asa, Social Thought and Social Action: A study of the work of Seebohm Rowntree, 1871-1954, (Longman), 1961.

[10] Seebohm Rowntree, B., Poverty: a study of town life, (Macmillan), 1899, reprinted, (Policy Press), 2000, 2nd ed., (Macmillan), 1901.

[11] Ibid, Seebohm Rowntree, B., Poverty: a study of town life, pp. 119-145.

[12] Ibid, Seebohm Rowntree, B., Poverty: a study of town life, pp. 86-118.

[13] Hennock, E.P., ‘Concepts of poverty in the British social surveys from Charles Booth to Arthur Bowley’, in Bulmer, Martin, Bales, Kevin and Sklar, Kathryn Kish, (eds.), The Social Survey in Historical Perspective, 1880-1940, (Cambridge University Press), 1991 and Hennock, E.P., ‘The measurement of urban poverty: from the metropolis to the nation, 1880-1920’, Economic History Review, Vol. 40, (1987), pp. 208-227.

[14] Bowley, A.L. and Burnett-Hurst, A.R., Livelihood and Poverty: A Study in the Economic Conditions of Working-Class Households in Northampton, Warrington, Stanley and Reading, 1915; see also, Carré, Jacques, ‘A.L. Bowley et A.R. Burnett-Hurst étudient les familles ouvrières à Reading en 1915’, in Carré, Jacques, (ed.), Les visiteurs du pauvre: Anthologie d’enquêtes britanniques sur la pauvreté urbaine, 19e-20e siècle, (Karthala), 2000, pp. 158-173.

[15] Rowntree, Seebohm, Poverty and Progress: A Second Social Survey of York, (Longman, Green and Co.), 1941, p. 461.