During the 1840s, there were two contradictory trends in matters of social policy. On the one hand there was a tendency to extend public control and, on the other, a tendency to call a halt to further change. The public health movement had to operate within the pressures produced by these opposing forces, pressures that in the end brought Chadwick‘s resignation and ended a stage in the history of social policy.

Public health was the fourth major area of policy, along with the poor law, factory reform and constabulary reform, with which Chadwick’s name was connected. The campaign bore the characteristic stamp of Chadwick’s mind. He propounded sanitary policies that tackled all parts of the problem and left no loose ends. He thought out an administrative structure at both central and local levels but his comprehensiveness and broad planning antagonised powerful vested interests. Nor were the plans free from Chadwick‘s characteristic dogmatism and they showed his distinctive inability to compromise or to modify his ideas.

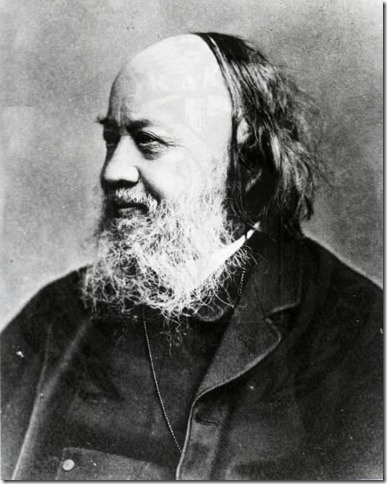

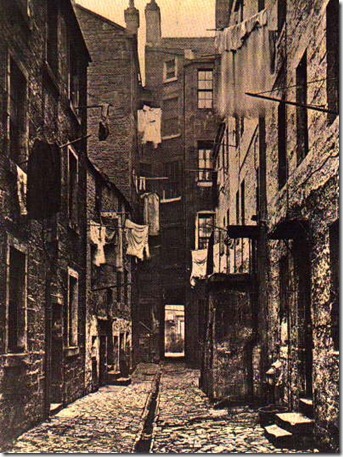

Enquiries had been made by Arnott, Southwood Smith and Kay into the sanitary conditions in East London in 1839. Chadwick‘s own Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain was published in 1842. [1] It was the result of two further years’ exhaustive work and it put the whole discussion of public sanitary policy onto an entirely new footing. Chadwick’s ideas dominated policy up to 1854. He believed that disease was carried by impurities in the atmosphere and that the great problem was to get rid of impurities before they could decompose.[2] The key to resolving the whole problem was the provision of a sufficient supply of pure water driven through pipes at high pressure. This would provide both drinking water and make it easier to cleanse houses and streets. Manure could be collected when it left the town and used as fertiliser in the surrounding fields.[3]

It was the very completeness of his solution that presented many problems. Water companies normally provided water only on certain days a week and at certain times. They did not provide it in either the quantity or at the pressure that Chadwick desired. Many houses in poorer districts had no water supply at all and no proper means of sewage disposal. Where sewers did exist they were often very badly regulated. Chadwick wished to replace the large brick-arched constructions with smaller egg-shaped types developed by John Roe. In addition to his first two basic ideas, the atmospheric theory of infection and the cyclical theory of water supply and drainage Chadwick maintained that proper central direction of sanitary planning should be combined with efficient local organisation, an idea parallel to his views on poor law and police.

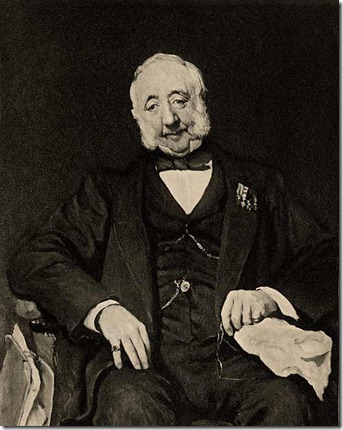

The 1842 Sanitary Report was complemented by a report the following year on interments in towns that exposed the terrible conditions of over-crowded graveyards of London.[4] These reports made a deep impression on public opinion and some 30,000 copies were initially printed. They were followed by a Royal Commission on the State of Towns, by a good deal of propagandist activity through the Health of Towns Association founded in December 1844, and eventually by the passage of the Public Health Act 1848.[5] Several points stand out in the Sanitary Report: Members and officials of existing commissions of sewers were generally examined in an unsympathetic, even hostile way. There were two authoritative statements of the views of reformers, one by Southwood Smith from the scientific and medical viewpoint, the other by Thomas Hawksley from an engineering viewpoint.[6] Complementing Hawksley’s evidence, there was evidence from other professional men about the importance of properly made plans and surveys as the pre-requisite for sound planning.

Portrait of Thomas Hawksley, H. Herkomer, 1887

By the middle of the 1840s, the local state was beginning to intervene in towns and several of the larger towns obtained private Acts to dealing with nuisances. In 1847 William Duncan became the Medical Officer for Liverpool, the first appointment in Britain.[7] By now the public health debate had polarised into those who favoured reform and those against it, characterised respectively as ‘The Clean Party’ and ‘The Dirty Party’ or ‘Muckabites’. [8]

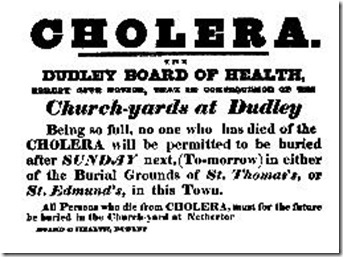

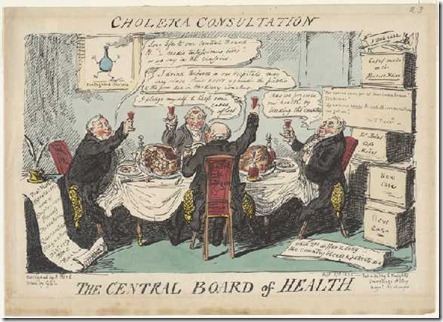

The central State did intervene in 1846 with the Nuisances Removal Act and particularly in the 1848 Public Health Act. The prime motivation behind both pieces of legislation was to combat the imminent cholera outbreak. The 1848 Act began the process of breaking down laissez-faire attitudes and established a Central Board of Health with a five-year mandate based at Gwydir House in London with three Commissioners (Lord Morpeth, Lord Shaftesbury and Chadwick, with Southwood Smith as Medical Officer). Local Boards of Health could be established where 10% of ratepayers petitioned the Central Board or would be set up in towns where the death rate was higher than 23 per thousand. The Local Boards of Health would take over the powers of water companies and drainage commissioners and could levy a rate and had the power to appoint a salaried Medical Officer. They also had the power to pave streets etc. but this was not compulsory.

There were several important weaknesses in the Act. First, the lifespan of the Central Board was limited to five years. Secondly, it was permissive in character and many towns did not take advantage of the Act. The large cities by-passed the legislation by obtaining private Acts of Parliament to carry out improvements and so avoided central interference: for example, Leeds in 1842, Manchester in 1844 and Liverpool in 1846. Thirdly, the Act was based on preventative measures and was therefore narrow in outlook. Such measures did bring about improvements but Chadwick paid no attention to contagionist theories and so alienated the medical profession. Finally, the Act did not legislate for London, which remained an administrative nightmare. The scale of the General Board’s operations was modest. By July 1853, only 164 places, including Birmingham, had been brought under the Act. In Lancashire only 26 townships took advantage of the Act and by 1858 only 400,000 of the county’s 2.5 million people came under Boards of Health.[9]

The litmus test for the success or failure of the new policies took place in London. A new Metropolitan Commission of Sewers had been set up in December 1847 of which Chadwick was a leading member.[10] From the outset there were bitter rivalries in the Commission between him and the representatives of the old sewer commissions and the parish vestries. In 1850, Chadwick produced a new scheme for the water supply and for a system of publicly controlled cemeteries. Both schemes aroused a host of opponents and both were abandoned. The Treasury refused to advance money for the purchase of private cemeteries and the Metropolitan Water Supply Act 1852 left the whole provision in the hands of water companies.[11]

By 1852, hopes for any comprehensive reform in London had been dashed and there was growing opposition to the General Board in the country as a whole. Lord Morpeth was replaced by Lord Seymour who was hostile to Chadwick. Feelings against the Board and Chadwick in particular rose orchestrated by The Times. The Central Board should have ended in 1853 but was given a year’s extension (1853-1854) because of a renewal of cholera. Chadwick knew that the ‘Dirty Party’ was intent on his destruction. He produced a report on what had been achieved but again criticised the various vested interests. Hostility in Parliament and from The Times and Punch focused on Chadwick who was seen as trying to bullying the nation into cleanliness. It was Seymour, who left office in 1852, who demanded the removal of the present Board members and successfully carried an amendment against the government’s bill to reorganise the Board. Chadwick resigned and never held public office again. The Central Board was officially abolished in August 1854 but was replaced by a new Board of Health (itself abolished in 1858). This was the end and on 12 August 1854 Chadwick ceased to be a commissioner. Though he lived until 1890, it marked the end of his active public career.

[1] Chadwick, Edwin, Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population, (W. Clowes and Sons), 1842, reprinted, Flinn, M.W., (ed.), (Ednburgh University Press), 1965.

[2] See, Hamlin, Christopher, ‘Edwin Chadwick, ‘mutton medicine,’ and the fever question’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 70, (1996), pp. 233-265.

[3] Goddard, Nicholas, ‘“A mine of wealth”? The Victorians and the agricultural value of sewage’, Journal of Historical Geography, Vol. 22, (1996), pp. 274-290 and Sheail, John, ‘Town wastes, agricultural sustainability and Victorian sewage’, Urban History, Vol. 23, (1996), pp. 189-210.

[4] Select Committee on the Improvement of Health in Towns, Supplementary Report on Internments in Towns, 1843.

[5] Paterson, R.G., ‘The Health of Towns Association in Great Britain, 1844-49: an exposition of the primary voluntary health society in the Anglo-Saxon public health movement’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 22, (1948), pp. 373-399.

[6] See also, evidence of Thomas Hawksley, First Report of the Commissioners for Inquiring into the State of Large Towns and Populous Districts, Minutes of Evidence, PP, (572), XVII.1, 1844, pp. 298-331.

[7] Fraser, W.M., Duncan of Liverpool: being an account of the work of W.H. Duncan, Medical Officer of Health of Liverpool 1847-63, (Hamish Hamilton), 1947.

[8] See Sigsworth, Michael and Warboys, Michael, ‘The public’s view of public health in mid-Victorian Britain’, Urban History, Vol. 21, (1994), pp. 237-250.

[9] Bain, Alexander, Autobiography, (Longmans, Green, and Co.), 1904, pp. 196-210 provides a civil servant’s view of Chadwick’s attempted reforms in London and the 1848 Act.

[10] Hanley, James G., ‘The metropolitan commissioners of sewers and the law, 1812-1847’, Urban History, Vol. 33, (2006), pp. 350-368, Darlington, Ida, ‘The London Commissioners of Sewers and their records’, Journal of the Society of Archivists, Vol. 2, (1962), pp. 196-210.

[11] Allen, Michelle Elizabeth, Cleansing the city: sanitary geographies in Victorian London, (Ohio University Press), 2008, pp. 24-85.