By the early 1830s, despite the work of these individuals and groups, there was a feeling that the Church was faced with the alternatives of thorough reform or ‘complete destruction’. [1] This fear was sufficient to remove the obstacles to organisational change and pastoral renewal that had long prevented its adjustment to industrial and urban society. The ecclesiastical and political crises of 1828-1832 were closely connected. The repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts in 1828, though they had little impact on the daily lives of Anglicans and Nonconformists, gave legitimacy to the ‘de facto’ situation. Catholic Emancipation in 1829 ended the civil disabilities against Catholics even if it had little impact on anti-Catholic sentiments and arguably may have increased them. This dramatically symbolised the failure of the old monopolistic and exclusive conception of the Establishment and its replacement by a pluralistic conception of religion. The blind conservatism of the Church of England’s leadership during the reform agitation, a conservatism motivated by a fear that the country was near revolution and that the church faced disestablishment, the 1832 Reform Act and the Whig electoral landslide meant that moderate reform could no longer be avoided. [2] The State increasingly took control of this ‘metamorphosis’ and the initiative for reform. The restructuring of the Establishment was something imposed by a Parliament that could not afford to wait for some consensus on reform to emerge within the Church itself. [3]

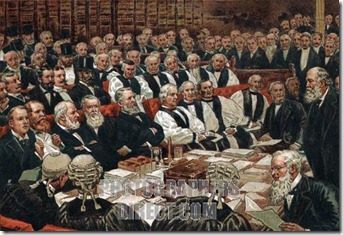

In June 1832, an Ecclesiastical Revenues Commission was established, but for two and a half years it had achieved little concrete. It investigated the financial structure of the Establishment but, as the debate about the Church intensified outside Parliament, proposals for reform were either defeated or allowed to lapse. The breakthrough came with the setting up of a new Commission to ‘consider the State of the Established Church’ in early 1835 during the minority Peel administration. It consisted of senior churchmen and Anglican politicians, including Peel, whose task was to prepare bills ready to present to Parliament to tackle the abuses that had been shown to be widespread in the Church of England. For Peel, it was essential for there to be ‘judicious reform’ to give ‘real stability to the Church in its spiritual character…I believe enlarged political interests will be best promoted by strengthening the hold of the Church of England upon the love and veneration of the community’. [4] Peel recognised that unless something was done quickly church reform might fall into the hands of politicians less sympathetic to the Anglican cause and possibly jeopardise the position of the Church as an Established body. By establishing a permanent body that involved the Church of England in initiating its own reform, Peel sought to encourage a greater sense of responsibility among Anglican leaders and hopefully shield the Church against further damaging attacks. [5]

The Ecclesiastical Commission survived the change in government in April 1835 and in 1836, Melbourne established it on a permanent basis as the Ecclesiastical Commission and, under the chairmanship of Charles James Blomfield, bishop of London, it quickly became the main instrument of organisational improvement in the Church. [6] It never became a government department answerable to Parliament through a minister and retained a degree of independence thought necessary if reform was to triumph over the opposition of vested interests in the House of Lords and in the Church at large. But, since the Church possessed no effective assembly or courts of its own, the initiative at the most vital points in the development of this body had to come from government. Major reforms of the Church’s structure occurred in the second half of the 1830s and during Peel’s ministry (1841-1846). The boundaries of existing dioceses were modified and new dioceses created in 1836; severe restrictions were placed on pluralism in 1838 and in 1840, excess revenues were distributed from cathedrals to those with greater needs. The Whigs also introduced the Registration Act in 1836 placing the registration of births, marriages and deaths in the hands of civil officials and not the Church and in 1838 the Dissenters’ Marriage Act ended the obligation of nonconformists to marry in an Anglican church. [7] A Populous Parishes Act was passed in 1843 empowering the Ecclesiastical Commission to create new parishes and providing the necessary stipends (payment for the vicar or curate) out of Church funds but it was clear to Peel that the cost of building new churches would have to be covered by the more efficient use of the Church’s existing resources and charitable contributions. [8] An impressive fund-raising campaign resulted in £25 million being spent on building and restoration work between 1840 and 1876. Improving the quality of the clergy proved a gradual process and the ideal of a fully-resident clergy remained difficult to put into practice and pluralism and non-residence remained relatively common until the 1870s. It should not be assumed that this necessarily resulting in poor standards of clerical attention to their parochial duties. Many of the rural clergy lived only a short distance from their parishes and were as efficient as they would have been had they been technically resident.

Of crucial importance in attempting to re-establish the popular position of the Church was resolving its financial grievances caused by the unpopularity of church rates and tithes. Though compulsory church rates were not abolished until 1868, legal judgements made it clear that they could only be collected where authorised by the churchwardens and a majority of the vestry. As Dissenters were eligible to vote for both, in some towns such as Birmingham the rate lapsed. This was preferable to Nonconformists than the scheme that the House of Commons seriously considered for repairing all parish churches from publiv funds. [9] The Tithe Commutation Act 1836 ended tithes in kind replacing them with money payments based on the average prices of corn, oats and barley over the previous seven years. [10]

The approach of the Commission was both radical and realistic. The decision to use excessive endowments to help poorer parishes resulted in 5,300 parishes being assisted in this way between 1840 and 1855. By 1850, the numbers of non-resident clergy had fallen significantly strengthening the work of the Anglican ministry. The increase in the pastoral efficiency of the clergy was accompanied by a decline in their status relative to other professions. The number of clergymen on the County Bench fell. The Church was saved in the 1830s and 1840s by giving up some of its social and secular administrative functions and by a further surrendering of its autonomy to the State. The religious dimension of the priestly office had become paramount. However, these initiatives did little to stem the numerical slide of the Church of England in urban and increasingly rural areas.

[1] On the problem of church reform see, Virgin, P., The Church in an Age of Negligence: ecclesiastical structure and the problems of church reform, (Cambridge University Press), 1989.

[2] Burns, R. Arthur, ‘The authority of the church’, in Mandler, Peter, (ed.), Liberty and authority in Victorian Britain, (Oxford University Press), 2006, pp. 179-200.

[3] For the role of the state see Brose, O., Church and Parliament: The Reshaping of the Church of England 1828-1860, (Cambridge University Press), 1959, Thompson, K. A., Bureaucracy and Church Reform: A Study of the Church of England 1800-1965, (Oxford University Press), 1970, and Machin, G. I. T., Politics and the Churches in Great Britain 1832 to 1868, (Oxford University Press), 1977.

[4] Parker, C. S., (ed.), Sir Robert Peel: from his private papers, 3 Vols., (John Murray), 1899, Vol. 2, p. 266.

[5] Dibdin, L. T., and Downing, S. E., The Ecclesiastical Commission: a sketch of its history and work, (Macmillan), 1919. See also, Manning, H. E., The Principle of the Ecclesiastical Commission examined, (J. G. & F. Rivington), 1838.

[6] Blomfield, Alfred, (ed.), A memoir of Charles James Blomfield, Bishop of London [1828-56], with selections from his correspondence, 2 Vols. (John Murray), 1863, and Johnson, Malcolm, Bustling intermeddler? The life and work of Charles James Blomfield, (Gracewing), 2001.

[7] Cullen, M. J., ‘The making of the Civil Registration Act of 1836’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 25, (1974), pp. 39-60, and Ambler, R. W., ‘Civil registration and baptism: popular perceptions of the 1836 act for registering births, deaths and marriages’, Local Population Studies, Vol. 39, (1987), pp. 24-31.

[8] Welch, P. J., ‘Blomfield and Peel: a study in cooperation between Church and State, 1841-6’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 12, (1961), 71-84.

[9] Brent, Richard, ‘The Whigs and Protestant dissent in the decade of reform: the case of church rates, 1833-1841’, English Historical Review, Vol. 102, (1987), pp. 887-910.

[10] At first this commutation reduced problems to the ultimate payers by folding tithes in with rents (however it could cause transitional money supply problems by raising the transaction demand for money). Later the decline of large landowners resulted in many tenants becoming freeholders and having to pay directly; this also led to renewed objections of principle by non-Anglicans. In 1936, the rent charges paid to landowners were converted by the Tithe Commutation Act to annuities paid to the state through the Tithe Redemption Commission. These payments were transferred to the Board of Inland Revenue in 1960 and finally ended by the Finance Act 1977. In Ireland, tithes were abolished in 1869 when the Church of Ireland was disestablished. In Scotland, teinds were not finally abolished until 2000.