If the development of the poor law system was an expression of the ‘collectivist impulse’, many groups and individuals were trying to tackle the worst evils on a voluntary basis.[1] In 1948, William Beveridge, the author of the modern welfare state, identified three distinct types of voluntary social service: first, philanthropy or the movement between the social classes, from the haves to the have-nots; secondly, mutual aid, the attempt by working men to support each other against the predictable crises in their lives: unemployment, sickness, disability, old age and to protect their dependants in the even of their early death; and finally, ‘personal thrift’ by making what provision was possible for oneself.[2]

There were bodies to meet every conceivable need: charities for the poor, the sick, the disabled, the unemployed, the badly-housed, charities for the reclamation of prostitutes and drunkards, for reviving drowning persons, for apprentices, shopgirls, cabbies, costermongers, soldiers, sailors and variety artistes. Sir James Stephen wrote in 1850

For the cure of every sorrow...there are patrons, vice-presidents and secretaries...For the diffusion of every blessing...there is a committee.’[3]

In 1833, Dr Thomas Griffith opened Wrexham’s first dispensary with the support of local gentry. Such was the demand for medical care that money was raised to build a proper infirmary in 1838. The hospital cost over £1,800 to build and a bazaar in the Town Hall during the Wrexham Races raised £1,050. The management of the infirmary reflected the contemporary values and would only treat those who could not afford to pay but patrons who regularly gave money could nominate poor people for medical treatment. As there was no government funding, all the money had to be raised by the community. Annual events such as the Wrexham Cyclists’ Club Carnival, Hospital Saturday and the Wrexham Infirmary Annual Ball and church collections and workers’ subscriptions all helped raise the money needed.

Charles Dickens captured the contradictions of Victorian philanthropy: the enormous need for charity in a society where want and plenty lived side-by-side and the inadequacy of much of the charity provided. Philanthropists appear throughout his novels, not just as a dramatic device to offer hope to impoverished characters but also as subjects in their own right. Some of his earlier characters have a positive role, such as Mr. Brownlow in Oliver Twist, the Cheeryble brothers in Nicholas Nickleby and Mr and Mrs Garland in The Old Curiosity Shop. But philanthropists were subjected to some acerbic ridicule in his later works. In Bleak House a novel mainly attacking the legal system, Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle are respectively guilty of ‘telescopic philanthropy’ and ‘rapacious benevolence’, neither of them helping to save the life of the child Jo, who dies of pneumonia.[4] In his final, unfinished, novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood Dickens ridiculed a selfish, paternalist attitude to philanthropy taking a direct swipe at the newly established Charity Organisation Society (COS). The character Mr. Honeythunder’s ‘Haven of Philanthropy’ would have been unmistakable to the readers of the day as a parody of the COS, or ‘Cringe or Starve’ as it was known by critics.[5]

Victorian philanthropy is a highly controversial subject. In its own day it was much admired buy by the 1960s, a reaction had set in. There was increasing awareness of the humiliation often involved in the ways recipients were offered ‘charity‘ and of the social climbing that often went with charity dinners, charity balls and royal patronage. Derek Fraser expresses this view in a mild, but pointed way:

The Victorian response to the powerlessness (or, as it was often conceived, the moral weakness) of the individual was an over-liberal dose of charity. The phenomenal variety and range of Victorian philanthropy was at once confirmation of the limitless benevolence of a generation and an implicit condemnation of the notion of self-help for all. It was small wonder that self-congratulation was so common a theme in contemporary surveys of Victorian philanthropy. So many good causes were catered for -- stray dogs, stray children, fallen women and drunken men... [6]

Neither the cynicism of today nor hero-worship of the past really explain the complexities of philanthropic activity in the Victorian period. Victorian philanthropy is an umbrella term covering a wide range of different activities that took place at many different places and in almost every community by people for a variety of very mixed motives.[7] During this period philanthropy changed both in methods and scope. There were at least four different, though overlapping phases.

Small-scale voluntary giving of the kind common in the eighteenth century: a landowner might look after his cottagers; a merchant might bequeath a sum of money for the relief of apprentices or indigent seamen or the aged poor of the parish. Pioneer work by individuals such as Florence Nightingale[8], Lord Shaftesbury[9], Dr Barnardo[10], General Booth of the Salvation Army[11], or Octavia Hill, the housing reformer, brought particular social evils to the public notice. Who were the pioneers and what motivated them? Many of them were neither rich nor aristocratic, though they all had time to spare from the daily grind of earning a living. Lord Shaftesbury was an exception among the landed classes, most of who confined their charitable activities to their own tenants. Many philanthropists came from the comfortable upper middle-class. Elizabeth Fry, the prison reformer, was the daughter of a banker and the wife of another. William Tuke, who founded the York Retreat, a model for the humane management of asylums, was a prosperous grocer. Florence Nightingale was the daughter of a wealthy dilettante. Others had a more precarious social background. Octavia Hill was a banker’s daughter but the family fell on hard times after her father’s death and the girls had to support themselves by some fairly low-level teaching. General Booth was the son of a speculative builder but was apprenticed to a pawnbroker at thirteen. Dr Barnardo went to work at the age of ten as a clerk in a wine merchant’s office. Most philanthropists were people of religious conviction. Shaftesbury was a leading Evangelical Churchman and his work as a reformer was a logical consequence of his faith. The Quaker contribution, by such families as the Frys, Tukes, Cadburys and Rowntrees, was particularly innovative.[12] Roman Catholics, Anglo-Catholics and Jewish groups were to develop their own organisation for social care in the second half of the century, but the Evangelicals led the way.

The major national societies and associations were often set up by the pioneers, but sometimes developed out of more widely supported local philanthropic effort.[13] In 1861, one survey estimated that there were 640 charitable institutions in London, of which nearly half had been founded in the first half of the century and 144 in the decade after 1850. By the late 1880s, the amount of money involved was substantial: voluntary societies in London alone were handling between £5.5 and £7 million a year.[14] The Times claimed that the income of London charities was greater than the governments of some European countries, ‘…exceeding the revenue of Sweden, Denmark and Portugal, and double that of the Swiss confederation.’[15]

The contribution of women to institutional charity, whether under male control or not, increased markedly after 1830.[16] In Birmingham, for example, many middle-class women became well known for their philanthropy and charitable work in the city: Mary Showell Rogers founded the Ladies Association for the Care of Friendless Girls;[17] Joanna Hill set up foster homes for pauper children;[18] Susan Martineau[19] helped establish a Homeopathic Hospital and worked to encourage poor people to save and Dr Mary Sturge was well known for her work at the Women’s Hospital.[20] The reason lies partly in the piety and need for ‘good work’s’ implicit in evangelicalism but also in the decline of middle-class female occupations. Throughout this period much of their work was paternalistic and conservative in character, concerned with the perennial problems of disease, lying-in and old age, drink and immorality. What was distinctive about women’s philanthropic enterprise was the degree to which they applied their domestic experience and education, their concerns about family and relations to the world outside the home.[21] It was a short step from the love of family to the love of the family of man, a step reinforced by the stress on charitable conduct by all religious denominations. The Evangelical concern with the importance of a proper home and family life can be seen as a move towards the more formal subordination of women that took place even in the more radical sects like the Quakers. Service and duty were implicit in both philanthropy and family life.

Practically every denomination had its own ‘benevolent’ society to cater for its own poor.[22] Anglicans, Nonconformists and Catholics all maintained their own charitable funds and in 1859 the Jewish board of Guardians was set up.[23] These religious societies were often the source of temporary charities in times of economic distress, either national or local. It is important to note that other types of society developed in this period. Visiting societies attempted to bridge the gap between the so-called ‘Two Nations’ through personal contact.

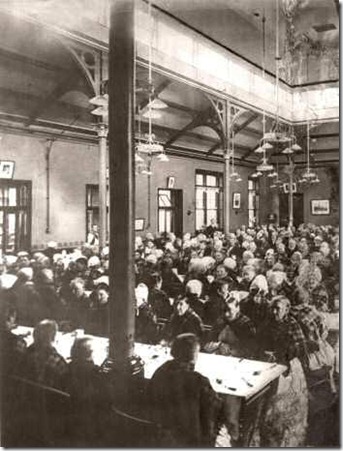

Lambeth Ragged School

The Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes was founded in 1841 to build new homes for the poor. This organisation practised what the Victorians called ‘5 per cent philanthropy’, where donors could invest their money for a good cause while receiving a respectable but below-market rate of return. The Relief Association launched in 1843 was an Anglican charity led by Bishop Blomfield. These societies made a positive effort to go out and see people in their own homes, while other societies were seeking to provide a sort of refuge for the needy. Housing charities such as the Peabody Trust sought to provide cheap homes for the working-classes but it was only Octavia Hill‘s housing experiments that really reached the destitute. Finally, ragged schools associated with Mary Carpenter[24] and Lord Shaftesbury provided rudimentary education.[25]

Most of the major modern charitable societies had their origins in the Victorian period and it is important to ask what motivated such a torrent of charity for the poor. It would appear that charity was a response to four types of motivation. First, there is little doubt that many in the upper and middle-classes had a genuine and persistent fear of social revolution and believed that charity could lift the masses from the depths of despair and out of the hands of radical agitators. Secondly, there was a society-wide increase in sensitivity to the suffering of others. Charity was a Christian virtue and many in the nineteenth century were moved to try and save souls in the belief that, as Andrew Reed with a lifelong concern with orphans and lunatics put it in 1840, ‘the Divine image is stamped upon all’.[26] A study of 466 wills published in Daily Telegraph in 1890s showed that men left 11% of their estates to charity and women left 25%. Increasingly, religious activity became socially oriented and religion became imbued with an essentially social conscience. Thirdly, charity was seen as a social duty to be done and be seen to be done. Charitable activity was imbued with social snobbery and a royal or aristocratic patron could considerably enhance a society’s prospects. Charity assumed the guise of a fashionable social imperative. Finally, charity was seen as a means of social control. Many philanthropists preached respectable middle-class values, cleanliness, sobriety, self-improvement and responsibility.The widespread practice of visiting was in effect a cultural assault on the working-class way of life. Poverty was seen by few as a function of the economic and social system. The majority assumed that it stemmed from some personal failing. Charity was a way of initiating a moral reformation, of developing the self-help mentality in individuals who would then be freed from the thraldom of poverty. Philanthropy was an essentially educative tool; in the words of C.S. Loch

Charity is a social regenerator...We have to use charity to create the power of self-help.[27]

Increasingly by the 1850s, doubts were expressed about the effectiveness of the multifarious charities. Two accusations were noted. There was a built-in inefficiency that was an almost inevitable result of the astonishing growth in the number of charities. There was a great deal of duplication of effort and much wasteful competition between rival groups in the same cause. There was sometimes conflict between London and the provinces in national organisations, and the same Church versus Dissent antagonism that characterised Victorian politics plagued Victorian charity. Charity was, like the Poor Law, counter-productive, helping to promote that very poverty is sought to alleviate. Although it may be an over-generalisation to say that the whole concept of charity tended to degrade rather than uplift the recipient, the radical William Lovett once remarked that

Charity by diminishing the energies of self-dependence creates a spirit of hypocrisy and servility.[28]

The problem was not lack of effort but the unscientific nature of much Victorian charity. The great divide in philanthropy was over whether to respond to immediate need, risking creating dependency or to help only the deserving, risking callousness. This was evident in the dispute between Thomas Barnardo and the COS. Inspired by his Christian faith, Barnardo began working with the poor in London’s East End in the late 1860s. He had a natural flair for publicity coining a good slogan, ‘No destitute child ever refused admittance’ and had great success raising funds using faked ‘before’ and ‘after’ photos of rescued children. The COS regarded Barnardo as an indiscriminate almsgiver and sought to discredit him. After a protracted and ugly legal battle, during which Barnardo’s right to the title ‘doctor’ was exposed as bogus since he never completed his studies and was forced to abandon the fake photographs, he was cleared of any wrongdoing.

The question of whether it reached those who needed it most was one of the main reasons for the creation of the Society for the Organisation of Charitable Relief and the Repression of Mendicity or Charity Organisation Society in 1869.[29] District Committees were established first in Marylebone led by Octavia Hill, then in St George-in-the-East and, within a year, there were seventeen. There was a constant struggle to recruit enough volunteers to staff the committees and do the work. Tensions were later to surface between the local and the authoritarian central committee. [30] In a paper read to the Social Science Association in 1869, significantly titled The Importance of aiding the poor without almsgiving, Octavia Hill set out what was to be the approach of COS. Charity, was a work of friendly neighbourliness and essentially private, should help and not harm. Any gift that did not make individuals better, stronger and more independent damaged rather than helped them.

Social problems, the COS believed, were ethical in origin, the result of free moral choices made by ‘calculating’ individuals. Poverty should spur individuals on to better their lot, to the benefit of all and charity should step in to help the destitute only if they were morally upright and provide training in personal responsibility. Pauperism was regarded as a social evil, a degraded mentality, even, according to Thomas Mackay a disease requiring scientific treatment that should be deliberatively punitive and stigmatising.[31] In practice, the COS wanted outdoor-relief under the Poor Law system to wither away, with a return to the rationale of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, restricting help to relief through workhouses. Over the years outdoor-relief had spread, and COS believed this was a corrupting sign of a dysfunctional society. It also meant that the Poor Law Guardians and the charities were competing for the same clients, each giving inadequate relief because of the other.

The COS was founded at the same time as an important policy statement from the Gladstone government known as the Goschen Minute instructing local Boards to co-operate with charities so that the Poor Law would relieve the undeserving in workhouses, charities the deserving poor and out-relief could be drastically reduced. George Goschen was President of the Poor Law Board and was concerned to tighten up the Poor Law, which he believed had become too generous, and its administration too lax. It is not clear who inspired who but the Goschen Minute formed the basis for the activities of the COS. Many of its members were also members of their local Boards of Guardians and they applied themselves with energy their tasks. Although most Boards were unsympathetic to the COS approach, in St George-in-the-East the COS had no less than six places and the chairman was Albert Peel who, from 1877 to 1898, also chaired the Central Poor Law Conference. In St George’s and later in Whitechapel and Stepney, outdoor-relief virtually disappeared and the Poor Law Board and COS worked hand-in-hand.

It is important to make a distinction between the social casework of COS and its social philosophy. [32] In its methods the COS was a pioneering body that was of great significance in the development of professional social casework in the nineteenth century. From the 1890s, they produced training manuals for this purpose, for the use of their volunteers. They also believed that loans, pioneered by the Jewish societies, were less ‘demoralising’ than gifts. The social philosophy of the COS was rigorously traditional and it became one of the main defenders of the self-help individualist ethic long after it had been challenged on all sides. The COS had an essentially dualistic attitude to its work: it was professionally pioneering but ideologically reactionary. The early leaders Charles Bosanquet, Edward Denison, Octavia Hill and above all Charles Loch[33] (secretary from 1875 to 1913) all believed that the casework methods should be geared to the moral improvement of the poor and that this was the real purpose of charity. All charities had to be on their guard against fraudulent applicants and this, for the COS, was justification for indiscriminate charity being ended by the vetting of every applicant.

By 1900, there were more than forty COS district offices in London and some 75 corresponding societies in other parts of the country. Their enquiries into individual cases were detailed, severe and highly judgmental, based on the conviction that poverty was a personal failing and that the poor needed to be forced back into self-sufficiency. The COS came into conflict with Dr Barnardo and opposed the Salvation Army with particular bitterness claiming that its work actually created homelessness. Their approach was abrasive, to both potential clients and other more compassionate relief organisations, and earned much of the opprobrium that has been since directed against philanthropy in general. Some within the COS became ‘reluctant collectivists’, recognising the need for limited extension of state action to address the problems endemic in late-Victorian capitalism and the rise of socialist ideas. Loch’s opposition to old-age pensions divided the COS in the 1890s but growing public support for pensions schemes resulted in its stance was attacked in the press in 1896.[34] This led to growing tensions since the District Committees resented being dictated to by the Council and being regarded as disloyal for advocating policies not approved by Loch. Loch answered this by speaking of two paths: one slow and difficult, leading to social independence, prosperity and stability for all; the other, that of liberal political expediency, dangerous, fatally expensive, and resulting in universal pauperisation. The dominance of the COS approach can be best seen in the Majority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor 1905-1909.[35]

Despite the opposition of the COS to state intervention and its continued opposition to indiscrimate philanthropy, some of its approaches were genuinely innovative. In 1871, it established a medical sub-committee which deplored the fact that 180,000 out-patients were treated annually at St Bartholomew’s Hospital without any enquiry and favoured the creation of charitable provident dispensaries and after-care centres especially for tuberculosis patients. A similar committee was set up to consider work with the ‘physically and mentally defective’ that pressed for better charitable provision for the blind and for the mentally ill and for children, the Invalid Children’s Aid Association was created though, not surprisingly, the COS opposed the spread of free school meals. A Sanitary Aid Committee was created in 1882 and some local inspectors appointed who helped to raise standards of hygiene. To assist the able-bodied to find work, they created a series of employment enquiry offices, the precursor of Labour Exchanges. The COS attempted to place a mass of unregulated charitable activity on a more constructive basis, but earned a reputation for rigidity and harshness in its approach to poor people. Much of the criticism directed against philanthropy relates to the operation of this organisation in the late-Victorian period. If any group gave charity a bad name, it was the COS. The problem was that the COS propounded its views in a manner that was punitive, moralistic and highly offensive to other charities.

[1] Gosden, P.H.J.H., Self-Help: Voluntary Associations in Nineteenth Century Britain, (Batsford), 1973 provides a detailed study of ways in which working people provided for themselves against poverty. It should be considered in relation to Hopkins, E., Self-Help, (UCL), 1995. Prochaska, F., The Voluntary Impulse, (Faber), 1988 is brief and pithy. Checkland, O., Philanthropy in Victorian Scotland: Social Welfare and the Voluntary Principle, (John Donald), 1980 extends the argument. Finlayson, G., Citizens, State and Social Welfare in Britain 1830-1990, (Oxford University Press), 1994 is perhaps the best book on the subject of voluntary efforts.

[2] Beveridge, William H., Voluntary Action, A Report on Methods of Social Advance, (Allen & Unwin), 1948, pp. 10-15.

[3] Stephen, J., Essays in Ecclesiastical Biography, 2 Vols. (Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans), 1850, Vol. 1, p. 382.

[4] Dickens, Charles, Bleak House, (Sheldon), 1863, pp. 271-297. See also, Christainson, Frank, Philanthropy in British and American fiction: Dickens, Hawthorne, Eliot, and Howells, (Edinburgh University Press), 2007, pp. 75-103.

[5] Dickens, Charles, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, (Chaman and Hall), 1870, (Plain Label Books), 1976, pp. 82, 85-86, 91-94, 300-310.

[6] Ibid, Fraser, D., The Evolution of the British Welfare State, 2nd ed., pp. 124-125.

[7] See, for example, Gorsky, Martin, Patterns of philanthropy: charity and society in nineteenth-century Bristol, (Boydell), 1999.

[8] Bostridge, Mark, Florence Nightingale: the woman and her legend, (Viking), 2008 is the most recent study but see also, Preston, M.H., Charitable words: women, philanthropy, and the language of charity in nineteenth-century Dublin, (Greenwood Publishing), 2004, pp. 127-174.

[9] See, Finlayson, G.B.M., The Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, 1801-1885, (Methuen), 1981.

[10] Wagner, G.M.M., Barnardo, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), 1979 and Williams, A.E., Barnardo of Stepney: the father of nobody’s children, 3rd ed., (Allen and Unwin), 1966.

[11] Green, R.J., The life and ministry of William Booth: founder of the Salvation Army, (Abingdon Press), 2005. See also, Walker, Pamela J., Pulling the devil’s kingdom down: the Salvation Army in Victorian Britain, (University of California Press), 2001.

[12] Isichei, Elizabeth Allo, Victorian Quakers, (Oxford University Press), 1970, pp. 212-251 considers philanthropy .Kennedy, Carol, Business pioneers: family, fortune and philanthropy: Cadbury, Sainsbury and John Lewis, (Random House), 2000.

[13] Prochaska, F.K., ‘Victorian England: the age of societies’, in Cannadine, David and Pellew, Jill, (eds.), History and philanthropy: Past, present and future, (Institute of Historical Research), 2008, pp. 19-32.

[14] See, for example, Dennis, Richard J., ‘The geography of Victorian values: philanthropic housing in London, 1840-1900’, Journal of Historical Geography, Vol. 15, (1989), pp. 40-54.

[15] The Times, 9 January 1885.

[16] Prochaska, F.K., Women and Philanthropy in Nineteenth Century England, (Oxford University Press), 1980, Lundy, Maria, Women and Philanthropy in nineteenth-century Ireland, (Cambridge University Press), 1995 and Preston, Margaret H., Charitable Words: Women, philanthropy, and the language of charity in nineteenth-century Dublin, (Greenwood Publishing), 2004. Mumm, Susan, ‘Women and philanthropic cultures’, in Morgan, Sue and de Vries, Jacqueline, (eds.), Women, Gender and Religious Cultures in Britain, 1800-1940, (Routledge), 2010, pp. 55-57 succinctly discusses the historiography of women’s philanthropy.

[17] Bartley, Paula, ‘Moral Regeneration: Women and the Civic Gospel in Birmingham, 1870-1914’, Midland History, Vol. 25, (2000), pp. 145-148.

[18] Hill, Florence Davenport, Children of the State, (Macmillan and Co.), 1889, pp. 17-19.

[19] Terry-Chandler, Fiona, ‘Gender and ‘The Condition of England’ Debate in the Birmingham Writings of Charlotte Tonna and Harriet Martineau’, Midland History, Vol. 30, (2005), p. 59.

[20] Oldfield, Sybil, (ed.), Women Humanitarians: A biographical dictionary of British women active between 1900 and 1950: ‘doers of the word’, (Continuum), 2001, p. 238.

[21] Changing attitudes can be seen in the contrast between Loudon, Mrs, Philanthropy: The Philosophy of Happiness, practically applied to the Social, Political and Commercial Relations of Great Britain, (Edward Churton), 1835 and Burdett-Coutts, Angela Georgina, (ed.), Woman’s Mission: A Series of Congress Papers on the Philanthropic Work of Women, by Eminent Writers, (S. Low, Marston & Company, Limited), 1893.

[22] Prochaska, F.K., Christianity and social service in modern Britain: the disinherited spirit, (Oxford University Press), 2006.

[23] Rozin, Mordechai, The rich and the poor: Jewish philanthropy and social control in 19th century London, (Sussex Academic Press), 1999

[24] See, Manton, J. Mary Carpenter and the children of the streets, (Heinemann), 1976.

[25] Swift, Roger, ‘Philanthropy and the children of the streets: the Chester Ragged School Society, 1851-1870’, Swift, Roger (ed.), Victorian Chester: essays in social history 1830-1900, (Liverpool University Press), 1996, pp. 149-184.

[26] Reed, Andrew and Reed, Charles, (eds.), Memoirs of the Life and Philanthropic Labours of Andrew Reed, D. D.: With Selections from His Journals, (Strahan & Co.), 1863, p. 384.

[27] Cit, Himmelfarb, Gertrude, The de-moralization of society: from Victorian virtues to modern values, (A.A. Knopf), 1995, p. 165.

[28] Lovett, William, Life and struggles of William Lovett in his pursuit of bread, knowledge, and freedom: with some short account of the different associations he belonged to and of the opinions he entertained, London, 1877, p. 142.

[29] Roberts, M.J.D., ‘Charity disestablished? The origins of the Charity Organisation Society revisited, 1868-1871’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 54, (2003), pp. 40-61.

[30] Humphreys, Robert, Poor relief and charity, 1869-1945: the London Charity Organisation Society, (Palgrave), 2001 and Mowat, C.L., The Charity Organisation Society, 1869-1913: its ideas and work, (Methuen), 1961.

[31] Mackay, Thomas, The State and Charity, (Macmillan and Co.), 1898, pp. 1-17, 134-177 and Mackay, Thomas, The English poor: a sketch of their social and economic history, (J. Murray), 1889, pp. 206-240 provide a summary of his views.

[32] Bosanquet, Helen, Social work in London, 1869 to 1912: a history of the Charity Organisation Society, (John Murray), 1914, Whelan, Robert, Helping the Poor: Friendly visiting, dole charities and dole queues, (Civitas), 2001, Woodroofe, Kathleen, ‘The Charity Organisation Society and the origins of social casework’, Historical Studies: Australia & New Zealand, Vol. 9, (1959), pp. 19-29 and Fido, Judith, ‘The Charity Organisation Society and social casework in London, 1869-1900’, in Donajgrodzki, A.D., (ed.), Social control in 19th century Britain, (Croom Helm), 1977, pp. 207-230.

[33] Loch, C.S., Charity and Social Life: a short study of religious and social thought in relation to charitable methods, (Macmillan and Co.), 1910.

[34] Macnicol. John, The politics of Retirement in Britain, 1878-1948, (Cambridge University Press), 1998, pp. 85-111 examines the attitudes of the COS to pensions.

[35] Ibid, Vincent, A.W., ‘The poor law reports of 1909 and the social theory of the Charity Organisation Society’, see also, Lewis, Jane, ‘The voluntary sector and the state in twentieth century Britain’, in Fawcett, Helen and Lowe, Rodney, (eds.), Welfare policy in Britain: the road from 1945, (Macmillan), 1999, pp. 52-68.