Friedrich Engels[1] wrote at the beginning of the chapter on ‘The Great Towns’ in his The Condition of the Working-class in England that

What is true of London, is true of Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, is true of all great towns. Everywhere barbarous indifference, hard egotism on one hand and nameless misery on the other, everywhere social warfare, every man’s house in a state of siege, everywhere reciprocal plundering under the protection of the law....[2]J.G. Kohl, a German visitor to Britain in the early 1840s, reported on the appearance of Birmingham

Birmingham, compared with Manchester is evidently deficient in large buildings and public institutions.... London has her Thames, Liverpool her Mersey....Birmingham has nothing of the kind, nothing but a dull and endless succession of house after house, and street after street.[3]By the time he reached Leeds, Birmingham‘s ugliness was forgotten

The manufacturing cities of England are none of them very attractive or pleasing in appearance, but Leeds is, perhaps, the ugliest and least attractive town in all England. In Birmingham, Manchester and other such cities, among the mass of chimneys and factories, are scattered, here and there, splendid newsrooms or clubs, and interesting exchanges, banks, railway-stations or Wellington and Nelson monuments. Leeds has none of these.[4]Alexis de Tocqueville noted in 1835 that

At Manchester a few great capitalists, thousands of poor workmen and little middle-class. At Birmingham, few large industries, many small industrialists. At Manchester workmen are counted by the thousand.... At Birmingham the workers work in their own houses or in little workshops in company with the master himself.... the working people of Birmingham seem more healthy, better off, more orderly and more moral than those of Manchester (where) civilised man is turned back almost into a savage.[5]Certainly, the built environments of Birmingham and Manchester were very different: there was less overcrowding in Birmingham and the quality of street cleansing and drainage was better than Manchester and other Lancashire towns.

It is tempting to arrange England’s industrial cities along a continuum of social and economic structure from Manchester at one extreme, as Engels called it ‘the classic type of a modern manufacturing town’ by way of Leeds where factories in the woollen industry were smaller than in Lancashire cotton, to Sheffield and Birmingham, the principal examples of workshop industry. This is misleading to several respects. It ignores the major seaports, many of which like Liverpool were also industrial cities. It suggests falsely that the satellites of each of the major cities could also be ranged alone a continuum paralleling that of the regional capital. Engels’ view of Manchester as the archetypal manufacturing city is misleading and other writers stressed that it was not typical.[6]

Spring Hill, Sheffield c1850

The massive increase in urban population resulted in a substantial physical increase of the built-up areas of towns. That, in turn, triggered a fundamental restructuring of urban land usage.[7] As with London, there was increasing segregation within urban communities largely as a response to a series of technological transformations.[8] In 1800, small-scale craft industries based on workshops scattered throughout the town produced for the local market. By 1900, two changes had occurred. First, large-scale, factory-based industries were established demanding extensive areas of land and accessibility to water and rail transport. The urban industrial region emerged. Secondly, workshop-based craft industries were eventually displaced. For example, the boot and shoemaker were eventually ousted by mass produced factory goods from the East Midlands; the tailor became a retailer of centrally produced off-the-peg garments. Manufacturing was concentrated into larger and distinctive regions within the town.

A whole series of changes also took place in retail technology though these were not completed until 1900.[9] Though they were not immediate and revolutionary, the end result was a radical change in the whole system. The weekly market was gradually replaced by, or transformed into, the permanent shopping centre. Up to 1850, the first stage was characterised by the building of a market hall. Michael Marks, for example, started in Leeds as a peddler or packman. By 1884, he had a stall in the open market that operated two days a week; from there he moved into the covered market that had been opened in 1857 on a daily basis; the next stage was to open stalls in other markets and by 1890 he had five. The old core of the town, or part of it, that had been a mixture of land uses became more specialised into retail or professional uses.

Mass produced goods undermined old local craft production and specialist retailers of manufactured goods replaced the old combined workshop-retailing establishments. The railways enhanced this process by providing speedy transport of even perishable commodities. Part of this process was the wider occurrence of the lock-up shop to which the retailer commuted each day. By the 1880s, both multiple and department stores appeared, the former especially in the grocery trade. Thomas Lipton started a one-man grocery store in Glasgow in 1872; by 1899, he had 245 branches throughout Britain. The greater demand for professional services, itself related to urban growth, resulted in lawyers and doctors seeking central locations. But a variety of other uses also located themselves here offering services to business, auctioneers and accountants or to the public, such as lending libraries.[10]

Upper Thames Street, Windsor, c1904

Transport technology has been examined previously but two aspects that greatly affected the towns. First, the impact of a developing railway system was a significant consumer of urban land. Secondly, in 1800, movement was primarily on foot: this has been called ‘the walking city’. By 1900, this had been transformed. The railway supplemented by the carriage, electric tram and omnibus were the main means of transport.[11]

Postcard of Tull’s Restaurant, Windsor c1903

Civic pride and civic rivalry among the industrial towns of the north were almost entirely materialistic in character and aesthetic issues played a lesser role. [12] The motives that inspired both were in part those of business. Sanitary reform made business sense as much as moral sense. Healthier workers would improve output and individuals and public authorities would be spared unproductive spending on hospitals and funeral charges. Certainly a social conscience inspired civic improvements but it is an error to neglect business needs. For the Victorians humanitarian and business aims were complementary not contradictory.[13]

Royal Crescent, Bath

In 1830, the prevailing style of Georgian urban design was theatrical, the prevailing aim one of spectacle.[14] Cities and towns had been rebuilt and refashioned with elegant assembly rooms, town halls, residential squares, parades and public gardens, settings for the rituals that helped shaped a variety of interests, landed, commercial, financial, professional into the cultural consensus of ‘polite society’. Classical styling established a common, nation-wide code for polite townscape as did other improvements to the fabric such as paving, lighting, street cleaning and the provision of piped water and sewage disposal. Noxious or dangerous trades were expelled to the districts of the poor. Other areas for the poor, notably town commons were liable to be enclosed for building genteel properties.

The building of a genteel townscape articulated a growing segregation between polite and impolite culture. But this division was never complete. The urban crowd, riotous and unpredictable, was always a threat. Aristocratic motives for restructuring towns and styles were in part patrician, an expression of an aristocratic conception of society, but they were also financial. Leading aristocrats in London, such as the Dukes of Bedford, Portland and Southampton, vied with each other to develop their estates.[15] Long-term leases realised long-term financial returns: urban land was cropped as effectively as arable soil.

Bedford Square (north side), London

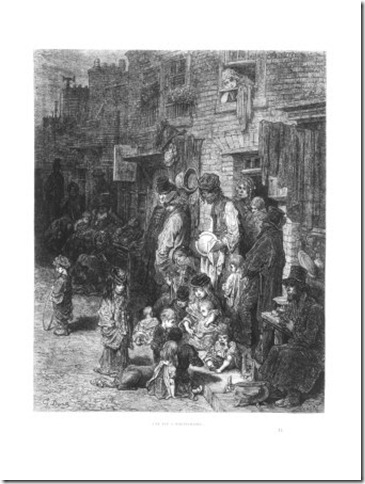

The lives and living conditions of the poor were largely ignored. But after 1830, spectacle was replaced by surveillance. This reflected the attitudes of social reformers who frowned on spectacular public display and city life generally became an object of concern. The conditions of the poor could no longer be ignored; they ceased to have walk-on roles and became central to the condition of towns. Contemporaries developed the idea of the ‘dangerous classes’ especially as the working-classes tended to be concentrated in particular areas of urban communities. The spectre of contagious diseases like cholera rampaging through towns and cities and with it a variety of social pathologies prompted Victorian reformers into more vigorous strategies for social and environmental control. Metropolitan improvements ceased to be schemes to beautify London but came to be limited to ones that deal with specific evils such as traffic congestion, insanitary buildings and inefficient sewage disposal in which aesthetic considerations were secondary. There were a number of schemes, both privately and publicly funded, to improve the physical fabric of poorer urban districts and, by extension, their moral and social condition. The wide streets, model housing estates and public parks were informed by the belief that slums nourished, if not caused, a variety of pathologies, not just physical disease but crime, laziness, irreligion and insurrection. At their core therefore schemes like this were concerned with principles of social discipline.[16]

As towns and cities expanded, early Victorian reformers voiced their concern about the loss of open space for public recreation. The crisis was not actually as great as reformers believed; open country was only a short walk away in most cities. The issue was the use to which open space was put.[17] Middle-class reformers promoted ‘rational recreation’, constructive kinds of leisure as opposed to the dog racing, prize fighting and political rallies that occurred round the northern industrial towns. The first purpose-built public park was the Arboretum in Derby opened in 1840 and the first municipal park was the more extensive Birkenhead Park opened four years later (soon known as ‘the people’s park’).[18] From the 1850s, new public parks and walks were built in most industrial towns and cities, often on the edges, sometimes by enclosing common land. Some were initially financed by large employers and then handed over to municipal corporations; others were municipal ventures from the outset. New cemeteries on the edge of cities were designed for rational recreation: Undercliffe Cemetery, high above Bradford, was run as a profit-making concern by local businessmen for families who walked beside extravagant tombs of the city’s leading industrial families.[19]

The Orangery, the Arboretum, Derby

From the reform of municipal corporations in 1835 environmental improvement was entwined with middle-class radicalism and attacks on what one Whig newspaper called ‘a shabby mongrel aristocracy’.[20] Between the mid 1830s and 1850s, there were bitter disputes between those who associated improvement with sewerage, drainage and water supplies and improvers who took a broader view of civil improvement and who sought to build a new civic townscape of broad open spaces and magnificent public buildings. With the revival of urban fortunes it was improvement on the grand scale that captured the corporate imagination. In 1873, Joseph Chamberlain was elected Birmingham’s mayor, a post to which he was re-elected in 1874 and 1875. [21] He focused on improving the physical condition of the town and its people. He organised the purchase of the two gas companies and the water works; he appointed a Medical Officer of Health, established a Drainage Board, extended the paving and lighting of streets, opened six public parks and saw the start of the public transport service. His Improvement Scheme saw the demolition of ninety acres of slums in the town centre. The council bought the freehold of about half the land to build Corporation Street. The experience of Birmingham was not, however, unique.

Undercliffe Cemetery, Bradford c1860

[1] Engels, F., The Condition of the Working-class in England in 1844, Leipzig, 1845; various editions including W.O. Henderson and W.H. Chaloner, (Blackwell), 1958, Victor Kiernan (Penguin), 1987 and Tristram Hunt, (Penguin), 2009. Carver, T., Engels, (Oxford University Press), 1981, McLellan, D., Engels, (Fontana), 1977 and Hunt, Tristram, The Frock-coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels, (Allen Lane), 2009 provide biographical detail.

[2] Ibid, Engels, F., The Condition of the Working-class in England in 1844, p. 68.

[3] Kohl, Johann Georg, England and Wales, (Chapman & Hall), 1844, reprinted, (Augustus M. Kelley), 1968, p. 6.

[4] Ibid, Kohl, Johann Georg, England and Wales, p. 49.

[5] Mayer, J.P., (ed.), Alexis de Tocqueville, Journeys to England and Ireland, (Transaction Publishers), 1988, p. 104.

[6] Trinder, Barrie, ‘Industrialising towns 1700-1840’, in ibid, Clark, Peter, (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 2 : 1540-1840, pp. 805-830 and Reeder, David and Rodger, Richard, ‘Industrialisation and the city economy’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 553-592.

[7] Englander, David, Landlord and Tenant in Urban Britain, 1838-1918, (Oxford University Press), 1983 and Offer, Avner, Property and Politics, 1870-1914: Landownership, Law, Ideology and Urban Development in England, (Cambridge University Press), 1981, 2010. See also, Gilbert, David and Southall, Humphrey, ‘The urban labour market’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 593-628.

[8] Pooley, Colin G., ‘Patterns on the ground: urban form, residential structure and the social construction of space’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 429-466.

[9] Benson, John and Ugolini, Laura, (eds.), A nation of shopkeepers: retailing in Britain, 1550-2000, (I.B. Tauris), 2002 provides a good overview. Cohen, Deborah, Household gods: the British and their possessions, (Yale University Press), 2006 and Baren, Maurice E., Victorian shopping, (Michael O’Mara), 1998 look at what people bought.

[10] Walton, John K., ‘Towns and consumerism’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 715-744.

[11] Armstrong, John, ‘From Shillibeer to Buchanan: transport and the urban environment’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 229-257.

[12] Morley, Ian, with a foreword by Richard Fellows, British provincial civic design and the building of late-Victorian and Edwardian cities, 1880-1914, (Edwin Mellen Press), 2008.

[13] Morris, Robert John, ‘Structure, culture and society in British towns’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 395-426.

[14] See, for example, Ayres, James, Building the Georgian city, (Yale University Press), 1998, Chalklin, C.W., The provincial towns of Georgian England: a study of the building process, 1740-1820, (Leicester University Press), 1974 Ison, W.W., The Georgian buildings of Bath: from 1700 to 1830, (Spire), 2004 and Summerson, J.H., Georgian London, (Pimlico), 1988, 2nd ed., (Yale University Press), 2003.

[15] See, for example, Byrne, Andrew, Bedford Square: An Architectural Study, (Athlone Press), 1990.

[16] Cunningham, Colin, Victorian and Edwardian Town Halls, (Routledge), 1981 provides insights into municipal building.

[17] Eyres, Patrick and Russell, Fiona, ‘Introduction: The Georgian Landscape Garden and Victorian Urban Park’, in Eyres, Patrick and Russell, Fiona, (eds.), Sculpture and the garden, (Ashgate), 2006, pp. 39-50.

[18] Elliott, Paul, ‘The Derby Arboretum (1840): the first specially designed municipal public park in Britain’, Midland History, Vol. 26. (2001), pp. 144-176.

[19] Clark, Colin and Davison, Reuben, In loving memory: the story of Undercliffe Cemetery, (Sutton), 2004.

[20] Cit, Webb, Sidney and Beatrice, The manor and the borough, Part 1, (Cass), 1908, p. 770.

[21] On Chamberlain in Birmingham the most recent study is Marsh, Peter, Joseph Chamberlain: Entrepreneur in Politics, (Yale University Press), 1994. See also, Rodrick, Anne Baltz, Self help and civic culture: citizenship in Victorian Birmingham, (Ashgate), 2004 and Thompson, D.M., ‘R.W. Dale and the “civic gospel”‘, in Sell, Alan P.F., (ed.), Protestant nonconformists and the west Midlands of England : papers presented at the first conference of the Association of Denominational Historical Societies and Cognate Libraries, (Keele University Press), 1996, pp. 99-118