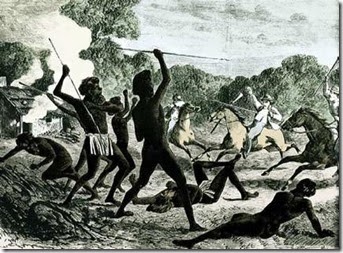

From the beginning, the nature of policing in the Port Phillip District, Victoria after 1851, was profoundly influenced by the need to overcome Aboriginal resistance to dispossession.[1] Aboriginal resistance expressed itself in a type of guerrilla warfare involving sporadic attacks on settlers, who were generally well armed and often shot Aboriginal people indiscriminately.[2] It is estimated that at least 20,000 Aboriginal people and approximately 3,000 settlers were killed across Australia in one hundred and fifty years of prolonged conflict.[3] The intensity of this conflict and Australia’s convict origins, accounts for the paramilitary nature of the settlement’s first police who, unlike their British counterparts, were heavily armed and military in appearance and operation.[4] Australia was the original police state.[5] Because Port Phillip was a free colony, not a penal settlement like NSW or VDL, Aboriginal people, rather than convicts, tended to be the major preoccupation of the colony’s early police.

When police were initially deployed around Port Phillip in 1836 their main task was to create a space in which settlement could grow, by keeping Aboriginal people off their own land once it was deemed fit for pastoral use. Alienation from the land deprived Aboriginal people of the material and spiritual basis for existence and all but destroyed their society. Although the official mandate of Port Phillip’s first police included protecting Aboriginal people and minimising conflict, the police sided with settlers, not only failing to protect Aboriginal people but joining in the killing.[6] This is hardly surprising given that police at the time were under the supervision of local magistrates, who were dominated by pastoralists. By the late 1830s, Aboriginal resistance in Port Phillip was met by a combination of Mounted, Border and Native Police. It was the latter force, however, established in 1837 and recruited from local tribes, who were in the vanguard in overcoming Aboriginal resistance. Port Phillip’s Native Police are said to have been relatively benign compared to their counterparts in other parts of the colony. ‘Relatively’, used in this context, must be kept in perspective. During the first years of European settlement, massacres, rapes and casual killings of Aboriginal people were so common they barely rated discussion. It is not possible to quantify precisely the extent of the carnage inflicted upon Aboriginal people by the Native Police of Port Phillip, because, as Bridges puts it, ‘naturally enough the more colourful, but illicit, exploits of the Corps were not enshrined for history in its official records’.[7]

Nevertheless, there is sufficient evidence to indicate that the killing of defenceless Aboriginal men, women and children by Port Phillip’s Native Police was of a scale that would be deemed unthinkable if it involved non-Aboriginals as victims. Summing up the role of the Native Police Corps in Port Phillip, Bridges maintained:

‘What it did do was to make the rule of force more effective through summary punishment, while operating to all appearances within the law, and by inhibiting depredation through fear. The Corps’s true task was a more basic one than that of white police for whites. If the Aborigines’ status as British subjects was ever to have any meaning, and if they were to live in peace with the destroyers of the native economy, they had in fact to be subjected to the will and code of the invader. The Corps was an instrument for forcing them to face this unwelcome fact.’[8]

Occasionally the Governor of Port Phillip encouraged prosecutions over the murder of Aboriginal people. Frontier society, however, was so dominated by those whose interests directly opposed those of its native inhabitants that prosecutions inevitably failed. For the most part, crimes against Aboriginal people by police and settlers were ignored; the charging of three Border police over the killing of two Aboriginals marking the exception rather than the rule. Police were not neutral in the conflict between settlers and Aboriginal people; instead they provided military reinforcement for the forced expansion of white settlement, thereby presiding over the wholesale destruction of Aboriginal society. The thoroughness of the destruction of Aboriginal life achieved with the help of Port Phillip’s police is attested to by the fate of its Native Police Corps. By the early 1850s, less than twenty years after the first police were sent to the district specifically to deal with the ‘Aboriginal problem’, there were so few Aboriginal people left that not only did the corps no longer have a reason to exist.[9]

[1] Ibid, Connell, R.W. and Irving H., Class Structure in Australian History: Poverty and Progress, p. 35 and ibid, Sturma, M. ‘Policing the criminal frontier in mid-nineteenth-century Australia, Britain and America’, p. 23.

[2] Bridges, B., ‘The Native Police Corps, Port Phillip District and Victoria, 1837-1853’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 57, (1971), pp. 113-142; Davies, S. ‘Aborigines, Murder and the Criminal Law in early Port Phillip’, 1841-1851’, Historical Studies, Vol. 22, (1987), pp. 313-335; Reynolds, H., Frontier: Aborigines, Settlers and Land, (Allen & Unwin), 1987, pp. 7-22; Broome, R., ‘The struggle for Australia: Aboriginal-European warfare’, 1770-1930 in McKernan, M. and Browne, M., (eds.), Australia: Two Centuries of War & Peace, (Allen & Unwin), 1988, pp. 102-103; and Elder, B., Blood on the Wattle: Massacres and Maltreatment of Australian Aborigines since 1788, (Child & Associates), 1988.

[3] Ibid, Reynolds, H., Frontier: Aborigines, Settlers and Land, pp. 7-9; 29-30; 53; ibid, Broome, R., ‘The struggle for Australia: Aboriginal-European warfare’, pp. 116-119.

[4] Haldane, R., The People’s Force: A history of the Victoria Police, (Melbourne University Press), 1986, pp. 5-39; ibid, Connell, R.W. and Irving H., Class Structure in Australian History: Poverty and Progress, p. 35; and, Palmer, D., ‘Magistrates, police and power in Port Phillip’ in Philips, D. and Davies, S., (eds.), A Nation of Rogues?: Crime, Law and Punishment in Colonial Australia, (Melbourne University Press), 1994, pp. 86-90.

[5] Davidson, A., ‘Big brother is watching you’, in ibid, Burgmann, V. and Lee, J., (eds.), Staining the Wattle: A People’s History of Australia since 1788, p. 3.

[6] Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Racist Violence: Report To The National Inquiry Into Racist Violence in Australia, (Australian Government Publishing Service), 1991, p. 39.

[7] Ibid, Bridges, B., ‘The Native Police Corps, Port Phillip District and Victoria, 1837-1853’, p. 126.

[8] Ibid, Bridges, B., ‘The Native Police Corps, Port Phillip District and Victoria, 1837-1853’, p. 130.

[9] Ibid, Bridges, B., ‘The Native Police Corps, Port Phillip District and Victoria, 1837-1853’, p. 130.