Between 1812 and 1822 six House of Commons’ Select Committees affirmed broad, if qualified, satisfaction with the civic jigsaw of parish-based watch systems. However, resistance to the notion of a police force lessened in the 1810s and early 1820s largely because of growing moral panic among the ruling class about working-class insurrection. In addition, while rising crime and disorder were still attributed by the urban middle-classes to the moral decay of the masses, there was an increasing willingness to critique the old criminal justice system as inefficient both in controlling crime control and providing public order and regulation.

Peel certainly argued in Parliament when introducing his Metropolitan Police Bill in 1828 that it would be more efficient than the existing uneven systems. However, he was not focussing simply on the safety of the streets or the protection of property and the main task of the new police was not crime detection. Peel’s reforms directly addressed the more general fear of the ‘dangerous classes’ and he saw crime as part of a more fundamental issue of public order. What was needed was moral discipline within the working-classes and this was going to be achieved by ‘crime prevention’. The police targeted alehouses and the streets where legislation such as the 1824 Vagrancy Act enabled constables to arrest individuals not for crime committed but for ‘loitering with intent’, putting the burden of proof on the defendant rather than the police. The police were concerned not simply with those who committed crimes but with the poor as a whole who were seen as a ‘criminal class’.

In starting from this broader conception of policing as general social control of the poor rather than simply crime control or even control of public disturbances, Peel was echoing an older tradition that had always seen policing as a wider function than crime control. Seeing the police as an essentially military force to secure the country against rebellion, rather than simply control crime and as a means of gathering intelligence was well established in Continental Europe. So those who saw the introduction of the police in the context of European developments had a point since Peel’s view of the police owed something to the Continental tradition. Peel recognised that establishing the Metropolitan Police as a military force similar to his reforms in Ireland would not be acceptable in England. He counted on the fears by the ruling class about revolution and of the middle-classes on the immorality of the working-classes to enable legislation to be successfully passed that combined the policing tasks of crime prevention, maintaining public order, moral regulation and instilling disciplined work and moral habits.

In 1828, a new Select Committee was appointed and, largely because it was composed of individuals sympathetic to his ideas, Peel secured a report broadly sympathetic to his aims. The Committee confirmed Peel’s earlier assessment of the system as intrinsically defective by virtue of its fragmented, non-uniform, and uncoordinated nature, something which would always defeat the best initiatives and efforts of individual parish forces. The proposed solution was predicable: a system of centrally directed and regulated police for the metropolis. The establishment of Peel‘s Metropolitan Police in 1829 embodied a conception of policing at odds with the discretionary and parochial procedures of eighteenth century law enforcement. However, he argued that a uniform system for the entire metropolis would mean that provision was not as dependent on the wealth of a parish. Full-time, professional, hierarchically organised, they were intended to be the impersonal agents of central policy.[1] The 1829 Metropolitan Police Act applied only to London. The jurisdiction of the legislation was limited to the Metropolitan London area, excluding the City of London and provinces.[2] This was an astute political decision on Peel’s part since the City was fiercely independent and had resisted other attempts to unify London’s police provision. Even today, the City of London had its own independent force, the result of a compromise in 1839. All London’s police were the responsibility of one authority, under the direction of the Home Secretary, with headquarters at Scotland Yard. 1,000 men were recruited to supplement the existing 400 police. Being a policeman became a full-time occupation with weekly pay of 16/- and a uniform. Recruits were carefully selected and trained by the Commissioners. Funds came from a new police rate levied on parishes by overseers of the poor and a receiver was appointed to take charge of financial matters. John Wray was appointed to the post and served until 1860.

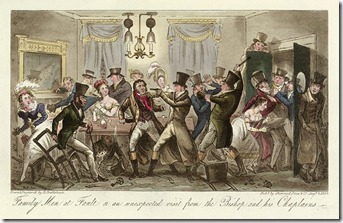

Parliament authorised the formation of the Metropolitan Police in July 1829 but the first constables did not take to the streets until September 1830. ‘Bobbies’ or ‘Peelers’ were not immediately popular. [3] Some parishes, especially the wealthier ones, objected to losing control over the ways they were policed. Most citizens viewed constables as an infringement on English social and political life and people often jeered the police. There were suspicions that Lieutenant-Colonel Rowan, a veteran of Wellington’s army, sought to establish a military force. However, both Peel and the Commissioners made deliberate attempts to ensure that the police did not take on the appearance of the military. Blue was deliberately chosen as the colour for uniforms to differentiate it from the red worn by the British army. Until 1864, top hats were worn by officers to emphasise their civilian character and beat officers were armed only with a truncheon. The preventive tactics of the early Metropolitan police were successful and crime and disorder declined. Their pitched battles with the Chartists in Birmingham and London in 1839 and 1848 proved the ability of the police to deal with major disorders and street riots. By 1851, attitudes to the police, at least in parts of London appears to have mellowed

The police are beginning to take that in the affections of the people that the soldiers and sailors used to occupy. In these happier days of peace, the blue coats, the defenders of order, are becoming the national favourites.[4]

The Metropolitan Police Act established the principles that shaped modern English policing. First, the primary means of policing was conspicuous patrolling by uniformed police officers. Secondly, command and control were to be maintained through a centralised, pseudo-military organisational structure. The first Commissioners were Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Charles Rowan (commissioner 1829-1850) and Richard Mayne (commissioner 1829-1868), a lawyer and they insisted that the prevention of crime was the first object of the police force.[5] During the 1830s, the Metropolitan Police absorbed several existing forces: the Bow Street Horse Patrol in 1836 and the Marine Police and the Bow Street Runners two years later. Thirdly, police were to be patient, impersonal, and professional. Finally, the authority of the English constable derived from three official sources: the Crown, the law and the consent and co-operation of the citizenry.

‘Peelers’ c1850

It has been suggested that as London’s crime-rate fell, that of nearby areas increased. The number of offences did seem to increase in areas of London where the police were not allowed to go. For example, Wandsworth became known as ‘black’ Wandsworth because of the number of criminals who lived there. As Chadwick pointed out in 1853

...criminals migrate from town to town, and from the towns where they harbour, and where there are distinct houses maintained for their accommodation, they issue forth and commit depredations upon the surrounding rural districts; the metropolis being the chief centre from which they migrate.[6]

[1] Most critical studies of policing stop around 1870-1880: Miller, W.R., Cops and Bobbies: Police Authority in New York and London 1830-1870, (Ohio State University Press), 1977, ibid, Emsley, Clive, Policing and its Context 1750-1870, Taylor, David, The new police: crime, conflict, and control in 19th-century England, (Manchester University Press), 1997 and Steedman, C., Policing the Victorian Community: The Formation of English Provincial Police Forces 1856-1880, (Routledge), 1984. Later themes can be teased out of ibid, Critchley, T.A., A History of Police in England and Wales 900-1966, Emsley, C., The English Police, (Longman), 2nd ed., 1996, Emsley, Clive, The Great British Bobby: A history of British policing from the 18th century to the present, (Quercus), 2009 and ibid, Ascoli, D., The Queen’s Peace: The Metropolitan Police 1829-1979.

[2] Mason, Gary, The official history of the Metropolitan Police: 175 years of policing London, (Carlton), 2004, Shpayer-Makov, Haia, The making of a policeman: a social history of a labour force in metropolitan London, 1829-1914, (Ashgate), 2001, Petrow, Stefan, Policing morals: the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office, 1870-1914, (Oxford University Press), 1994 and Smith, P.T., Policing Victorian London: political policing, public order, and the London Metropolitan Police, (Greenwood Press), 1985.

[3] Campion, David A., ‘“Policing the Peelers”: Parliament, the public and the Metropolitan Police, 1829-33’, in Cragoe, Matthew and Taylor, Antony, (eds.), London politics, 1760-1914, (Palgrave), 2005, pp. 38-56.

[4] ‘The Police and the People’, Punch, Vol. 21, (1851), p. 1`73.

[5] The term ‘commissioner’ was given legislative legitimacy in the Metropolitan Police Act 1839. Before that, Rowan and Mayne were only Justices of the Peace.

[6] Second Report from the Select Committee on the Police with the Minutes and Appendix, Parliamentary Papers, Vol. 36, 1853, Appendix 5, pp. 170-171.