The recently reported discovery of a possibly unique copy of the National Chartist Hymn Book in Todmodern Library has raised the neglected question of the significance of hymns and hymn singing and more broadly religion to the Chartist movement. [1] Elizabeth Gaskell, especially in Mary Barton seems to suggest that suffering is something that Christians have to accept and she repeatedly insists that the only way people can be happy is to resign themselves to God’s will. During the nineteenth century, the Church of England and those Nonconformist churches that sought ‘respectability’ used to insist on this point as well and it seemed to many Chartists that the Church had become an accomplice of the middle-class by keeping the poor quiet and resigned to their suffering fate. Throughout the novel, the protagonist John Barton questions whether poverty is in fact God’s will or whether it was brought about by the incessant greed of the rising middle-class. The ways the working-class is presented suggests that the only way that the laws which had enriched the middle-class were to be changed would be by Chartism.

Given that Chartism was a cultural as well as a political movement, it is not surprising that religion and religious belief, whether orthodox or not, played a significant role in determining the character of the movement and that in that process hymns played a major role. A quick search of the Northern Star identified 447 references to hymns ranging from advertisements for non-sectarian hymn books to the singing of hymns at the beginning and often the end of Chartist meetings. The state had politicised the Church and Chartist recognised the practical and symbolic importance of attacking this religious hegemony in their extended campaigns for the vote. For example, during August and September 1839, Chartists in South Wales began attending their local parish churches in large numbers, something many regular worshippers could not understand as the attitude of churches to the Chartists had changed little. The Baptists in their association meetings at Risca deplored the level of disaffection and insubordination shown by Chartists. In June, a Wesleyan minister, expressing broader views in his denomination had accused them of being levellers, thieves and robbers. [2] Nonetheless, on 11 August they marched to the parish church of St Woolos in Newport for both morning and evening services. A week later, at Merthyr, the Chartists peaceably crowded into the parish church where the curate, Thomas Williams, who had been informed of their intentions preached an aggressive sermon from the text: ‘Submit yourselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake; whether it be to the King as supreme or unto Governors...’ [3] The following week, Chartists listened to a sermon at Pontypool while in Abedare and Hirwaun, Chartists specifically asked John Davis an Independent minister to preach to them. Although he produced a scriptural justification for the doctrine of the rights of man, he begged them to abstain from physical violence and not raise the sword against their fellow man. Was attendance at church, as David Williams suggests ‘a cloak to cover nefarious designs’? [4] This misreads their significance and widespread occurrence. [5] Religion helped to give Chartists strength, sanctify their crusade and face the possibility of dying in the struggle. For many, millenarian Christianity emphasised historical change brought about by an awakened people. In occupying church pews, Chartists were asserting their moral authority but were also showing their contempt for the Anglican usurpation of Christianity and the Constitution and this was even more the case in South Wales where the church represented an alien culture and government. Christianity was just as capable of being democratised as political institutions. [6]

The discovery of the Todmorden booklet raises important questions about the importance of hymn singing to Chartists. Sold for one penny, it was obviously aimed at the mass market. So why were hymns important to the Chartists. There had been two earlier attempts at producing a hymn book for the whole movement: Thomas Cooper edited the Shakesperian Chartist Hymn Book published in 1842 and Joshua Hobson’s Hymns for Worship: Without sectarianism and adapted to the present state of the church, with a text of scripture for each hymn published the following year. Cooper’s Shakesperian Chartist Hymn Book gave both the hymn and Shakespeare a new oral agitational and political resonance by attempting to give both Bardic and religious authority to Chartist lyrics. [7] It collects together songs and ballads of the indigenous rank and file ‘Chartist poets’ and demonstrates the importance of orality to the movement. The hymns were meant to be memorised and so even the illiterate could participate in the process of collective worship and agitation. The dominant poetic tradition is, as a result, startled into new meanings or new purpose by using traditional literary forms in differing socio-political contexts and stressing the latent energy and orality of popular lyric forms. The development of Chartist hymns represented an extension of the radical ballad narrative into the religious domain combining perceptions of the intense feeling and vision about the alienation they felt from the dominant middle-class industrial culture with a morality tale that allowed them to articulate in accessible ways both their religious and political solidarity and the identification of their grievances through a populist oral tradition against those who failed to recognise or were unwilling to accommodate those demands.

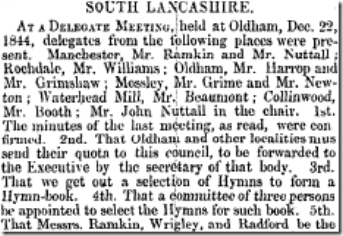

The origins of the National Chartist Hymn Book can be tentatively identified in the pages of the Northern Star. On 28 December 1844,

On 1 February 1845,

A month later, on 1 March, the Northern Star included the following,

By 23 August 1845, the book was nearing publication or had already been published

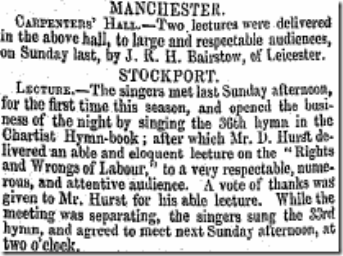

Finally, on 1 November 1845, it is clear that the Chartist Hymn-Book was in use, though given the reference to the ‘36th hymn’, whether this was the book found in Todmorden is debatable and is more likely to be a reference to Hobson’s 64 page book:

Heavily influenced by dissenting Christians, the hymns are about social justice, ‘striking down evil doers’ and blessing Chartist enterprises, rather than the conventional themes of crucifixion, heaven and family. Some of the hymns protested against the exploitation of child labour and slavery. Another of the hymns proclaimed: ‘Men of wealth and men of power/ Like locusts all thy gifts devour.’ Two of the hymns celebrate the martyrs of the movement. Great God! Is this the Patriot’s Doom? was composed for the funeral of Samuel Holberry, the Sheffield Chartist leader, who died in prison in 1843, while another honours John Frost, Zephaniah Williams and William Jones, the Chartist leaders transported to Tasmania in the aftermath of the Newport rising of 1839.

For the remainder of the pamphlet see: http://www.calderdale.gov.uk/wtw/search/controlservlet?PageId=Detail&DocId=102253&PageNo=1

There is no music. This came later to hymn books and singers would have fitted the words to tunes they were already familiar with. Each hymn is marked with the metre of the hymn and this would have helped them know how the words went with the rhythm. Mike Sanders, who will undoubtedly write a detailed paper on his find commented,

‘This fragile pamphlet is an amazing find and opens up a whole new understanding of Chartism – which as a movement in many ways shaped the Britain we know today.’

[1] Its discovery was reported widely in the press; see, for example, Lancashire Telegraph, 21 December 2010.

[2] Western Vindicator, 20 July 1839.

[3] I Peter ii, verses 13-17.

[4] Williams, David, John Frost: A Study in Chartism, (University of Wales Press), 1939, p. 187.

[5] Yeo, Eileen, ‘Christianity in Chartist Struggle 1838-1842’, Past & Present, Vol. 91 (1981), pp. 109-139, identified demonstrations in Sheffield over five consecutive weeks as the most protracted but there were others, for example in Stockport, Norwich and Bradford.

[6] Jones, Keith B., ‘The religious climate of the Chartist insurrection at Newport, Monmouthshire, 4th November 1839: expressions of evangelicalism’, Journal of Welsh Religious History, Vol. 5, (1997), pp. 57-71.

[7] See, Janowitz, Anne, F., Lyric and Labour in the Romantic Tradition, (Cambridge University Press), 1998, pp. 136-137, Roberts, Stephen, The Chartist Prisoners: The Radical Lives of Thomas Cooper (1805-1892) and Arthur O’Neill (1819-1896), (Peter Lang), 2008, p. 78, and Roberts, Stephen, ‘Thomas Cooper in Leicester, 1840-1843’, Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions, Vol. 61, (1987), pp. 62-76, at pp. 70-71. See also, Murphy, Andrew, ‘Shakespeare among the Workers’, in Holland, Peter, (ed.), Shakespeare Survey: Writing about Shakespeare, (Cambridge University Press), 2005, pp. 111-112