Notions of the ‘country’ and the ‘town’ have always roused strong feelings and evoked powerful images. They have also created fundamental opposites. The ‘country’ was seen either as a natural way of life, of peace, innocence and simple virtue or as a place of ignorance, backwardness and obstruction. Round the ‘town’ clustered either the idea of it as a centre of achievement, of learning and communication or as a place of worldliness, noise, ambition and corruption. Like all stereotypes these polarities contain some truth.[1]

Towns and cities were a characteristic feature of British society in this period. By 1851, Britain was overwhelmingly an urban society and that trend continued and accelerated through to 1914. The nineteenth century saw the transformation of British society from one where one in four people lived in towns or cities to one in which over two out of three people lived in built-up areas. This urbanisation was not without its cost in human misery and deprivation, in appalling housing and polluted conditions and in ‘sweated’ workshops. But towns were also places of elegance, of conspicuous spending and wealth, resplendent with their civil buildings and parks and their sense of ‘civic pride’ and were seen by many as symbols of ‘progress’. Towns and cities were places of intense contrasts. This was not new since they had always been places of contrast. Many of the problems such as housing and sanitation existed in the medieval and early modern town.[2] What was new, however, was the scale and expansion of towns and cities and this exacerbated their problems. The economic changes that originated in the eighteenth century led to the rapid expansion of urban centres. Towns, especially those in the forefront of manufacturing innovation, attracted rural labour, which hoped for better wages and a sense of freedom. The notion that ‘town air is free air’ was nothing new; it has its origins in medieval Germany. But labourers saw towns as places free from the paternalism and dependency of the rural environment and flocked there in their thousands.[3] For some migration brought wealth and security. For the majority life in towns was little different, and in environmental terms probably worse, from life in the country. They had exchanged rural slums for urban ones and exploitation by the landowner for exploitation by the factory master. Poverty was universal and few, whether rural or urban could escape from it.[4]

Between a sixth and a fifth of the total population of England lived in London. Its functions were plural. It was the largest city in the world containing the country‘s biggest concentration of industry chiefly clothing, footwear and furniture.

According to the 1851 census, 86% of London‘s employers employed fewer than ten men but some large establishments could be found such as the Woolwich Arsenal with 12,000 people in 1900 and the main railway works of the Great Eastern Railway at Stratford employing around 7,000 a decade later. The port of London was the country‘s largest and, as the epicentre of railways and roads, London was undoubtedly the chief emporium of Britain and its empire. London was the functional and ceremonial seat of politics and diplomacy, the first place of finance and the professions and the most important stage for the world of art, literature and entertainment. It was the centre and magnet for all things from luxurious living and High Society.

Defining London is not easy for the historian. To the Metropolitan Board of Works and the London County Council, established in 1855 and 1888-1889 respectively, it was an administrative province. To the City Corporation it was the jealously guarded enclave of about one square mile and almost immeasurable wealth. To the Registrar-General in charge of censuses London was an over-spilling, almost indeterminate, urban area. Some statistical definition was given to the concept of Greater London in 1875 when it was made to correspond to the Metropolitan Police District with a radius of fifteen miles from Charing Cross. Overall, from 1861 to 1911, the population of the administrative county grew by 61%, the Greater London conurbation 125% compared to 80% in England as a whole.[5]

The newspaper editor R.D. Blumenfeld wrote in his diary on 15 October 1900

Everybody wants to come to London; and little wonder, since the rural districts are all more or less dead, with no prospect of revival.[6]

One of the major causes of the expansion of London was migration. More women than men were migrants. Domestic service and the prospect of marriage were prevailing forces. In addition, women’s opportunities of fieldwork were reduced in the late nineteenth century and a more scientific milk trade was eliminating the ordinary milkmaid. The number of women returned in censuses as agricultural workers fell from 229,000 in 1851 to 67,000 by 1901. The majority of in-migrants were aged between 15 and 30, a situation that made the over-supply of unskilled, casual labour in the capital worse. The Royal Commission on the Poor Laws (1905-1909) showed than in London people aged over 60 made up 67 per 1,000 population compared to 102 per 1,000 in mainly rural areas. The greater the city the wider its magnetic attraction and in the case of London, this extended overseas.

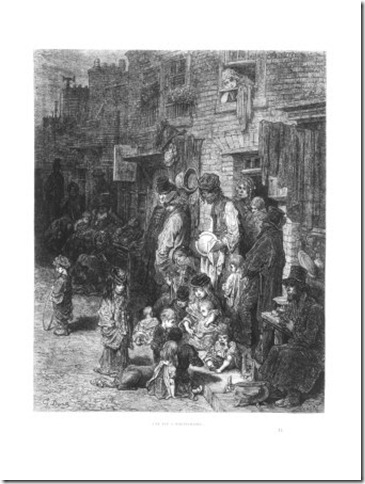

Wentworth Street, Whitechapel, c.1880

East European pogroms brought an additional 100,000 to 150,000 Jewish immigrants to England between 1881 and 1914.[7] Leeds, Manchester and, to a lesser extent, Liverpool were also destinations but the heaviest concentration was in East London. Whitechapel’s population in 1901 was 31.8% alien. The proportion of foreign-born in the total population of London increased from 1.57% in 1881 to 2.98% in 1901.[8] The number of Irish-born immigrants, especially in the old East End, was highest before 1860 but fell in the late nineteenth century. Most migrants from the English countryside reached London from a short distance and the proportion of migrants was proportional to the distance of their homes from the capital. Railways certainly increased the volume of migration but did not substantially alter its character. Most people moved short distance in a series of stages.

The proportion of migrants in London‘s population was falling in the nineteenth century. In the period 1851-1891, 84% of London’s increase in population came from the surplus of births, only 16% from net immigration. This feature radically distinguished London from major European cities. Two causes were outstanding. First, the superior sanitary provision of England resulted in a falling death rate. Secondly, there was an outflow of population to suburbs. This was particularly obvious in London. The square mile of the City had a resident population that peaked around 1850 at 130,000 but had dropped to 27,000 by 1901: this should be contrasted with the increase in its daytime or working population that rose from 170,000 in 1865 to 437,000 by 1921. The decline of the working-class population of the City resulted in them being jammed into the adjacent East End. Suburban railways and the underground, as well as enhanced omnibus services meant that the middle-class could move to the outer ring of Greater London; East and West Ham, Leyton, Tottenham, Hornsey, Willesden, Walthamstow and Croydon.[9]

What in an average English town was the work of one or two sanitary and housing departments was in London split between many bodies.[10] The options available to the LCC and before 1889 the Metropolitan Board of Works were unattractive and freedom of manoeuvre small. Each of the 28 Metropolitan Borough Councils (and before them, the vestries[11]) had concurrent powers with the LCC. Each was also a sanitary authority and it was their duty to overcome overcrowding and its associated problems. There was considerable difficulty in co-ordinating local government. The LCC could build but it was the responsibility of other local authorities to provide tenants with other services. Even when the LCC did build council properties the tenants were not generally displaced slum dwellers. The high price of land in London restrained the whole of the LCC‘s activity as it had to pay on average 35% higher prices per acre than provincial local authorities.

Slum clearance without providing cheap alternative accommodation made the housing situation worse. Low cost travel from homes built on cheaper suburban land was a possible solution. There was, however, a substantial time lag before needs and abilities with respect of transport, work, wages and rents approached anything like a match. For this period most of the London‘s inner-city poor were cramped in overcrowded, high-rent housing in order to remain in walking distance of work. As C.F.G. Masterman wrote in 1903

Place a disused sentry-box upon any piece of ground in South or East London and in a few hours it will be occupied by a man and his wife and family, inundated by applications from would-be lodgers.[12]

There was some improvement in overcrowding but in 1911, 27.6% of people in the inner London area were living more than two per room. This situation was not helped by the higher rents of ordinary working-class homes: in 1908, they were 70% higher than in Birmingham.

London slum

The pressure was greatest in the East End. The housing problems of London serve to illustrate several points of general importance with regard to urban development in this period. London was a living laboratory for experiment in the housing question, for individual and company philanthropy, for private enterprise and for collective public action. From 1883, the exposures of Andrew Mearns’ The Bitter Cry of Outcast London and stimulated a debate that led to the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working-classes (1884-1885). [13] There was little new in The Bitter Cry but its popularity can be explained by the sensationalist publicity it received in the Pall Mall Magazine and the climate of working-class discontent and middle- and upper-class insecurity existing in London in the 1880s. Mearns’ choice of a memorable title helped boost sales of the work and his decision to focus on the homes of the poor not merely street life was a radical departure from earlier studies. The pamphlet also hinted at horrors too ghastly to be included and this further stimulated people’s shocked emotions. [14] It also gave stimulus to investigative social work in the Settlement Movement[15], later investigative studies [16] and especially Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London.

Unregulated individualism was put on trial and, as rents rose and accommodation shortages spiralled out of control. The conclusion was emerged from this experience was that national government could not permanently stand aside since at the heart of the problem was an uneven distribution of wealth and resources. [17] Graduated direct taxation and state subsidies to local council housing were the courses that were eventually adopted. There was, and arguably still is, in the words of Joseph Chamberlain in 1883 on the Torrens and Cross housing legislation

...an incurable timidity with which Parliament...is accustomed to deal with the sacred rights of property.[18]

There were many Londons. Contemporaries noted the difference of East and West End, and the character of north and south of the river and the enclaves of Westminster and the City. It was, however, the East End that dominated contemporary comment. Writers like Walter Besant[19] and George Gissing[20] focused attention on the enormity of its problems.[21]

The East End consisted of the parishes east of Bishopsgate Street, stretching north of the Thames to the River Lea. By 1900, however, new industrial developments, the opening of the Royal Albert Dock and the Great Eastern Railway’s provision of workmen’s train services meant that East London also now included the working-class dormitories east of the Lea and south of Epping Forest. By 1900, this swollen East London contained nearly two millions people. It was virtually a one-class community with few amenities.[22] However, the work of East London displayed extraordinary variety but was mostly carried out in small workshops rather than large factories.

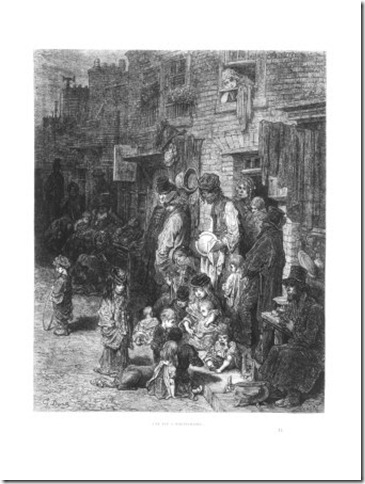

Frying Pan Alley, London, c.1890

The East End spanned the working-class spectrum from the sweated trades, the casual and under-employed workers who predominated in the western part and along the waterfront, to the regularly employed and quietly respectable artisans in the Poplar, Bow and Bromley districts. Each parish had its own character: some metal work but mainly cheap clothing, cigar and food preparation dominated Whitechapel; furniture, silk and toys predominated in Bethnal Green and Shoreditch; boots and shoes in Mile End; and, weaving in Spitalfields.[23] East London contained many technical inventions but also a darker side with sub-contracting, sweating, irregularity of demand and low wages. Craftsmanship survived but rarely in its totality; for example, watch makers often made only one part of a watch and used mass-produced parts for the remainder

Charles Booth‘s study of East London is an important source for the social composition of East London and provides a valuable corrective to the gloom of contemporary novelists such as Gissing. [24] He divided society into eight classes from A to H: A to F spanned the lower classes and classes G and H were the lower middle and upper middle-classes. Booth found that higher artisans (class F) made up about 13.5% of the population. B to D made up 30%, those with small regular earnings and intermittent earnings. Class E was varied but brought together most artisans and regular wage-earners and was the largest category at 42%; the lowest class A was about 1.25% of the population comprising ‘some occasional labourers, street-sellers, loafers, criminals and semi-criminals’. This study is important in several respects. It rendered insupportable generalisations about a tidal wave of wretchedness and viciousness gaining on society and about to engulf it. Booth rejected the view that misery was all pervasive and irremediable.

Petticoat Lane, 1903

He did, however, suggest that the state of East London had been worse in the past than in the 1890s. Certainly by 1860, there was a crisis in London’s inner industrial areas as civic improvements elsewhere in the metropolis shunted thousands into adjacent working-class parishes and resulted in a cruel spiral of rising rents and increased overcrowding.[25] Workers found themselves under increasing pressure because there was insufficient cheap, plentiful or well-timed transport to, from and within the suburbs resulting in many working people being trapped in East London. The casual labour of the old East End was trapped within an economy of declining trades and conditions of employment deteriorated. By the early 1870s, London‘s shipbuilding had slumped beyond the point of recovery and by the 1880s most heavy engineering, iron founding and metal work had gone the same way. Competition from provincial furniture, clothing and footwear factories could only be met by reducing labour costs and led to the mounting importance of sweated trades.[26] London‘s industries found themselves increasingly under pressure and this had two consequences. First, the disadvantages of the least skilled were cruelly exposed. Secondly, the ‘respectable’ working-class found themselves pushed down into competing for the same work and accommodation as the casuals: this marked a dilution of labour status.[27]

The conventional middle-class perception of East London was of a foggy, malarial urban landscape, a place where revolutionary tempers might grow to overthrow society. London was an image of their fear of the streets, aversion from crowds and anxiety about impersonality. London was a place of anonymity. Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford, said in a talk on ‘the London we live in’ in 1864

He looked out of the bedroom windows of the little inn in which he was staying at the surging crowd which passed and re-passed beneath him; and he could have screamed for someone who knew him or knew somebody who knew.... This feeling of isolation in the midst of a vast crowd was absolutely painful.[28]

The rapidity of growth startled the middle- and upper-classes. London was too extensive to be grasped, too impersonal to be understood. Many reacted to London as the poet Rudyard Kipling did to Chicago: ‘Having seen it, I urgently desire never to see it again.’[29]

The influence of London, throughout the southeast and further, was increasingly immeasurable. The capital city had grown and spread to the point of virtual amorphousness, unorganised and unorganisable. The persistent feature of London in this period was the warning it gave about cities generally: their overwhelming power to defeat those who tried to control their overall movement and development.

[1] The issue of town and country is discussed in Williams, Raymond, The Country and the City, (Chatto), 1973 and some of its implications for an industrialising society in Weiner, M., English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit 1850-1950, (Cambridge University Press), 1982. The agenda for urban historians was set in 1968 in Dyos, H.J., (ed.), The Study of Urban History, (Edward Arnold), 1973 and the extent to which developments occurred in the following decade in Fraser, D. and Sutcliffe, A.J., (eds.), The Pursuit of Urban History, (Edward Arnold), 1983. Waller, P.J., Town, city and nation: England 1850-1914, (Oxford University Press), 1983 is a succinct study. Ibid, Clark, Peter, (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 2: 1540-1840 and ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950 are essential.

[2] On small towns, see, Clark, Peter, ‘Small towns 1700-1840’, in ibid, Clark, Peter (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 2: 1540-1840, pp. 733-774 and Royle, Stephen A., ‘The development of small towns in Britain’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 151-184

[3] On this issue, see, Feldman, David, ‘Migration’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 185-206.

[4] The development of town and city can be approached through Briggs, Asa, Victorian Cities, (Penguin), 1968, Dennis, R., Industrial Cities of the Nineteenth Century, (Cambridge University Press), 1984, Dyos, H.J. and Wolff, M., (eds.), The Victorian City: Images and Realities, two Vols. (Routledge), 1973 and ibid, Waller, P.J., Town, City and Nation, England 1850-1914. There are several useful studies of specific cities: Olson, D.J., The Growth of Victorian London, (Batsford), 1976, Fraser, D., (ed.), A History of Modern Leeds, (Manchester University Press), 1980, Hopkins, E., The Rise of the Manufacturing Town: Birmingham and the industrial revolution, (Sutton), 1998, Daunton, M., Coal metropolis, Cardiff 1870-1914, (Leicester University Press), 1977. See also, Williamson, J.G., Coping with City Growth during the British Industrial Revolution, (Cambridge University Press), 1990 that adopt a statistical approach to the issues of urban growth; and, Koditschek, T., Class Formation and Urban Industrial Society: Bradford 1750-1850, (Cambridge University Press), 1990, that considers in depth the social and economic development of a ‘boom’ town. Morris, R.J. and Rodger, R., (eds.), The Victorian City: A Reader in British Urban History 1820-1914, (Longman), 1994 collects together important papers and has an excellent introduction that puts urban growth in its context.

[5] Schwarz, Leonard D, ‘London 1700-1840’, in ibid, Clark, Peter, (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 2: 1540-1840, pp. 641-672 and Dennis, Richard, ‘Modern London’, in ibid, Daunton, Martin J., (ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Vol. 3: 1840-1950, pp. 95-131 provide an excellent overview.

[6] Blumenfeld, R.D., In the Days of Bicycles and Bustles, (Brewer and Warren), 1930, (Read Books), 2007, pp. 94-95.

[7] On Jewish migration in the second half of the nineteenth century and the role of Jewish labour in London see Feldman, David, Englishmen and Jews: Social Relations and Political Culture 1840-1914, (Yale University Press), 1994 and Endelman, Todd M. The Jews in Britain 1656 to 2000, (University of California Press), 2000, pp. 79-182. See also, Stallard, Joshua Harrison, London pauperism amongst Jews and Christians: An inquiry into the principles and practice of out-door relief in the metropolis, and the result upon the moral and physical condition of the pauper class, (Saunders, Otley, and Co), 1867, Wechsler, R.S., The Jewish garment trade in East London 1875-1914: a study of conditions and responses, (Columbia University Press), 1979 and Berrol, Selma Cantor, East Side/East End: Eastern European Jews in London and New York, 1870-1920, (Praegar), 1994.

[8] Ibid, Lees, L. Hollen, Exiles of Erin: Irish Migrants in Victorian London and ibid, Jackson, J.A., ‘The Irish in East London’, East London Papers, Vol. 6, (1963), pp. 105-119

[9] On the development and impact of the underground, see Wolmar, Christian, The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How it Changed the City Forever, (Atlantic Books), 2004. Jackson, Alan A., ‘The London Railway Suburb 1850-1914’, in ibid, Evans, A.K.B. and Gough, John, (eds.), The impact of the railway on society in Britain: essays in honour of Jack Simmons, pp. 169-180.

[10] See, for example, Hardy, A., ‘Parish pump to private pipes: London’s water supply in the 19th century’, in Bynum, W.F. and Porter, R., (eds.), Living and dying in London, (Wellcome Institute), 1991, pp. 76-93.

[11] The vestry had its origins in medieval England having been established as early as the fourteenth century to manage church affairs. However, in the early modern period it became a general administrative body. In large industrialising parishes or in places where the leading inhabitants formed executive committees, known as ‘select vestries’, most of the population were excluded. Inevitably the vestry began to involve itself in every aspect of local administration because it had the right to set parish rates to finance the work of its officials. Its influence only declined after 1834 when it lost its responsibilities for the poor law to the Poor Law Unions with their Boards of Guardians. In 1894, it was finally replaced by parish councils.

[12] Masterman, C.F.G., From the Abyss: Of Its Inhabitants, (R.B. Johnson), 1903, reprinted (Garland Press), 1980, p. 12.

[13] Mearns, Andrew, The Bitter Cry of Outcast London: An Inquiry into the Condition of the Abject Poor, (James Clarke & Co), 1883, reprinted edited by A.S. Wohl, (Leicester University Press) 1970 and extracts in Keating, P., (ed.), Into Unknown England 1866-1913, (Fontana), 1976, pp. 91-111. There is some debate as to whether Andrew Mearns or William Preston was the author. The pamphlet was certainly either written or heavily revised by Rev. William C. Preston with Rev. James Munro helping with the research and composition of the work as well.

[14] Under William T. Stead, the Pall Mall Magazine devoted a great deal of space to promoting the pamphlet and between mid-October and early November 1883, published at least one article a day on ‘Outcast London’. Supported by the Daily News, and with a combination of sensationism and moral righteousness, Stead was able to keep the public’s atention focused on the London poor for the next two months.

[15] Hamilton, Richard, ‘A hidden heritage: The social settlement house movement 1884-1910’, Journal of Community Work and Development, Vol. 2, (2), (2001), pp. 9-22 and Meacham, Standish, Toynbee Hall and social reform, 1880-1914: the search for community, (Yale University Press), 1987.

[16] See, Sims, G.R., How the Poor Live: And, Horrible London, (Chatto & Windus), 1898 and Wilson, Keith, ‘Surveying Victorian and Edwardian Londoners: George R. Sims’ Living London’, in Phillips, Lawrence, (ed.), A mighty mass of brick and smoke: Victorian and Edwardian representations of London, (Rodopi), 2007, pp. 131-149.

[17] On the revival of the ‘condition of England question’, see, Haggard, Robert, F., The Persistence of Victorian Liberalism: the politics of social reform in Britain, 1870-1900, (Greenwood Publishing), 2001, pp. 27-52

[18] Chamberlain, Joseph, Fortnightly Review, Vol. 40, (1883), p. 767.

[19] Besant wrote several books on London including East London, (Century Co.), 1901 and South London, (Chatto & Windus), 1899. In both he was highly critical and was capable of dismissing as of no account the greater part of London that was not the City or West End. The Lumpenproletariat East London and artisan and petty-bourgeois South London were each for him a travesty of urban civilisation.

[20] George Gissing was the most gifted novelist to employ late-nineteenth century London as a backcloth to his fiction. Whether writing of working-class Clerkenwell and Hoxton, as in The Nether World, (Smith, Elder and Co), 1889 and Demos: A Story of English Socialism, (Harper & Brothers), 1886 or artisan and petty-bourgeois Camberwell, in In the Year of the Jubilee, (Lawrence and Bullen), 1894, the picture of the streets was of drab squalor. Gissing’s London was the London of defeat, a nightmare region; in The Nether World, p. 205 ‘beyond the outmost limits of dread’ and p. 167, ‘a city of the damned’. His urban world was barren, barbaric and beyond redemption.

[21] Domville, E.W., ‘“Gloomy City, or, the deeps of Hell”: the presentation of the East End in fiction between 1880 and 1914’, East London Papers, Vol. 8, (1965), pp. 98-109.

[22] See Steffel, R.V., ‘The evolution of a slum control policy in the East End, 1889-1907’, East London Papers, Vol. 13 (1970), pp. 23-35.

[23] Leech, Kenneth, ‘The decay of Spitalfields’, East London Papers, Vol. 7, (1964), pp. 57-62. See also, Kerchen, Anne J., Strangers, aliens and Asians: Huguenots, Jews and Bangladeshis in Spitalfields, 1660-2000, (Routledge), 2005.

[24] Booth, Charles, Life and Labour of the People in London: Vol. 4, The trades of East London, (Macmillan), 1893.

[25] On conditions in London in the 1860s the standard work is Jones, Gareth Steadman, Outcast London: a study in the relationship between classes in Victorian society, (Oxford University Press), 1971 where the ‘arithmetic of woe’ can be seen graphically illustrated. See also the contemporary prints by the French artist Gustave Doré.

[26] See, Hall, P.G., ‘The East London footwear industry: an industrial quarter in decline’, East London Papers, Vol. 5, (1962), pp. 3-21 and Oliver, J.L., ‘The East London furniture industry’, East London Papers, Vol. 4, (1961), pp. 88-101.

[27] Brodie, Marc, The politics of the poor: the East End of London 1885-1914, (Oxford University Press), 2004.

[28] Cit, ibid, Waller, P.J., Town, City and Nation, England 1850-1914, p. 49.

[29] Kipling, Rudyard, From sea to sea: letters of travel, (Doubleday, Page and Co.), 1900, p. 276.