My blog looks at different aspects of history that interest me as well as commenting on political issues that are in the news

Saturday 15 June 2019

How did Palmerston secure British interests 1830-1841?

Sunday 11 November 2018

My Books and other publications

Those publications with an asterisk (*) were co-written with C.W. Daniels. This list does not include editorials for Teaching History, book reviews or unpublished papers. Neither does it include the two series of books for which I have been joint-editor: Cambridge Topics in History and Cambridge Perspectives in History. Including these books would increase the length of this appendix by 52 books.

1974-1979

Computer-based data and social and economic history (for the Local History Classroom Project), (1974).

Social and Economic History and the Computer (for LHCP), (1975).

‘Local and National History -- an interrelated response’, in Suffolk History Forum, 1977.

‘Our Future Local Historians’, in The Local Historian, Vol. 13, 1978. *

‘Sixth Form History’, in Teaching History, May 1976. *

‘Sixth Form History’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 3 June 1977. *

‘The new history -- an essential reappraisal’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 2 December 1977. *

‘Interrelated Issues’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 1 December 1978. *

‘The Myth Exposed’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 30 November 1979 * also reprinted in John Fines (ed.) see below.

1980-1984

Nineteenth Century Britain, (Macmillan), 1980. *

‘The Local History Classroom Project’, in Developments in History Teaching, (University of Exeter), 1980. *

‘A Chronic Hysteresis’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 5 December 1980. *

Twentieth Century Europe, (Macmillan), 1981. *

‘Is there still room for History in the secondary curriculum?’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 5 December 1981. *

‘Content considered’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 9 April 1982. *

Twentieth Century Britain, (Macmillan), 1982. *

‘A Level History’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 8 April 1983. *

‘History in danger revisited’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 9 December 1983. *

‘History and study skills’, in John Fines (ed.), Teaching History, (Holmes McDougall), 1983.

‘History and study skills’, reprinted in School and College, Vol. 4, (4), 1983.

Four scripts for Sussex Tapes, 1983:

People, Land and Trade 1830-1914.

Pre-eminence and Competition 1830-1914.

The Social Impact of the Industrial Revolution.

Lloyd George to Beveridge 1906-1950.

Four computer programs for Sussex Tapes, 1984:

The Industrial Revolution.

Population, Medicine and Agriculture.

Transport: road, canal and railway.

Social Impact of Change.

‘It’s time History Teachers were offensive’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 28 November 1984. *

The Chartists, (Macmillan), 1984. *

1985-1989

‘Using documents with sixth formers’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 29 November 1985. *

Learning History: A Guide to Advanced Study, (Macmillan), 1986. *

GCSE History, (The Historical Association), 1986, revised edition, 1987, as editor and contributor.

‘Training or Survival?’ with M. Booth and G. Shawyer in The Times Educational Supplement, 10 April 1987.

Change and Continuity in British Society 1800-1850, (Cambridge Topics in History, Cambridge University Press), 1987.

‘There are always alternatives: Britain during the Depression’ for BBC Radio, 14 September 1987.

‘Cultural imperialism’, in The Times Educational Supplement, 4 December, 1987.

‘The Training of History Teachers Project’, in Teaching History, 50, January 1988.

‘History’ in Your Choice of A-Levels, (CRAC,) 1988.

‘The Development of Children’s Historical Thinking’ with G. Shawyer and M. Booth, Cambridge Journal of Education, Vol. 18, (2), 1988.

‘The New Demonology’, Teaching History, Vol. 53, October 1988.

The Future of the Past: History in the Curriculum 5-16: A Personal Overview, (The Historical Association), 1988.

‘History Study Skills: Working with Sources’, History Sixth, Vol. 3, October 1988. *

‘A Critique of GCSE History: the results of The Historical Association Survey’, Teaching History, Vol. 55, March 1989.

1990-1999

‘History Textbook Round-up’, Teachers’ Weekly, September 1990.

‘Partnership and the Training of Student History Teachers’, with M. Booth and G. Shawyer, in M. Booth, J. Furlong and M. Wilkin (eds.), Partnership in Initial Teacher Training, (Cassell), 1990.

Economy and Society in Modern Britain 1700-1850 (Routledge), 1991.

Church and State in Modern Britain 1700-1850 (Routledge), 1991.

‘History’ in Your Choice of A-Levels, (CRAC), 1991.

‘Lies, damn lies and statistics’, Teaching History, 63, April 1991.

‘BTEC and History’, in John Fines (ed.), History 16-19, (The Historical Association), 1991.

‘What about the author?’, Hindsight: GCSE Modern History Review, Vol. 2, (1), September 1991.

‘Appeasement: A matter of opinion?’, Hindsight: GCSE Modern History Review, Vol. 2, (2), January 1992.

Economic Revolutions 1750-1850 (Cambridge Topics in History, Cambridge University Press), 1992.

‘Suez: a question of causation’, Hindsight: GCSE Modern History Review, Vol. 4, (1), September 1993.

‘History’ in Your Choice of A-Levels, (CRAC,) 1993.

History and post-16 vocational courses’, in H. Bourdillon (ed.), Teaching History, (Routledge), 1993.

‘Learning effectively at Advanced Level’, pamphlet for PGCE ITT course, (Open University), 1994.

Preparing for Inspection, (The Historical Association), 1994.

Managing the Learning of History, (David Fulton), 1995.

Chartism: People, Events and Ideas (Perspectives in History, Cambridge University Press), 1998.

BBC History File: consultant on five Key Stage 3 programmes on Britain 1750-1900, 1999.

2000-2009

Revolution, Radicalism and Reform: England 1780-1846, (Perspectives in History, Cambridge University Press), 2001.

‘The state in the 1840s’, Modern History Review, September 2003.

‘Chartism and the state’, Modern History Review, November 2003.

‘Chadwick and Simon: the problem of public health reform’, Modern History Review, April 2005.

2010

Three Rebellions: Canada 1837-1838, South Wales 1839, Eureka 1854, (Clio Publishing), 2010.

2011

Three Rebellions: Canada 1837-1838, South Wales 1839, Eureka 1854, (Clio Publishing), 2011 Kindle edition.

Famine, Fenians and Freedom, 1840-1882, (Clio Publishing), 2011.

Economy, Population and Transport (Nineteenth Century British Society), 2011 Kindle edition.

Work, Health and Poverty, (Nineteenth Century British Society), 2011 Kindle edition.

Education, Crime and Leisure, (Nineteenth Century British Society), 2011 Kindle edition.

Class, (Nineteenth Century British Society), 2011 Kindle edition.

2012

Religion and Government, (Nineteenth Century British Society), 2012 Kindle edition.

Society under Pressure: Britain 1830-1914, (Nineteenth Century British Society), 2012 Kindle edition.

Sex, Work and Politics: Women in Britain, 1830-1918, (Authoring History), 2012.

Famine, Fenians and Freedom, 1840-1882, (Clio Publishing), 2012 Kindle edition.

Sex, Work and Politics: Women in Britain 1830-1918, 2012, Kindle edition.

Rebellion in Canada, 1837-1885 Volume 1: Autocracy, Rebellion and Liberty, (Authoring History), 2012.

Rebellion in Canada, 1837-1885, Volume 2: The Irish, the Fenians and the Metis, (Authoring History), 2012.

2013

Resistance and Rebellion in the British Empire, 1600-1980, Clio Publishing, 2013.

Settler Australia, 1780-1880, Volume 1: Settlement, Protest and Control, (Authoring History), 2013.

Settler Australia, 1780-1880, Volume 2: Eureka and Democracy, (Authoring History), 2013.

Rebellion in Canada, 1837-1885, 2013, Kindle edition.

'A Peaceable Kingdom': Essays on Nineteenth Century Canada, (Authoring History), 2013.

Resistance and Rebellion in the British Empire, 1600-1980, 2013, Kindle edition.

Settler Australia, 1780-1880, 2013, Kindle Edition.

Coping with Change: British Society, 1780-1914, (Authoring History), 2013.

2014

Before Chartism: Exclusion and Resistance, (Authoring History), 2014.

Suger: The Life of Louis VI 'the Fat', (Authoring History), 2014, Kindle edition.

Chartism: Rise and Demise, (Authoring History), 2014.

Sex, Work and Politics: Women in Britain, 1780-1945, (Authoring History), 2014.

Before Chartism: Exclusion and Resistance, (Authoring History), 2014, Kindle edition.

2015

Chartism: Rise and Demise, (Authoring History), 2015, Kindle edition.

'Development of the Professions', in Ross, Alastair, Innovating Professional Services: Transforming Value and Efficiency, (Ashgate), 2015, pp. 271-274.

Chartism: Localities, Spaces and Places, The Midlands and the South, (Authoring History), 2015.

Chartism: Localities, Spaces and Places, The North, Scotland Wales and Ireland, (Authoring History), 2015.

2016

Chartism, Regions and Economies, (Authoring History), 2016.

Breaking the Habit: A Life of History, (Authoring History), 2016.

Chartism: Localities, Spaces and Places, The Midlands and the South, (Authoring History), 2016, Kindle edition.

Chartism: Localities, Spaces and Places, The North, Scotland Wales and Ireland, (Authoring History), 2015, Kindle edition.

Chartism, Regions and Economies, (Authoring History), 2016, Kindle edition.

Suger: The Life of Louis VI 'the Fat', revised edition, (Authoring History), 2016.

Robert Guiscard: Portrait of a Warlord, (Authoring History), 2016.

Chartism: A Global History and other essays, (Authoring History), 2016.

Chartism: A Global History and other essays, (Authoring History), 2016, Kindle edition.

Roger of Sicily: Portrait of a Ruler, (Authoring History), 2016.

Three Rebellions: Canada, South Wales and Australia, (Authoring History), 2016.

2017

Famine, Fenians and Freedom, 1830-1882, (Authoring History), 2017.

Disrupting the British World, 1600-1980, (Authoring History), 2017.

Britain 1780-1850: A Simple Guide, (Authoring History), 2017.

People and Places: Britain 1780-1950, (Authoring History), 2017.

2018

Britain 1780-1945: Society under Pressure, (Authoring History), 2018.

Britain 1780-1945: Reforming Society, (Authoring History), 2018.

Three Rebellions: Canada, South Wales and Australia, (Authoring History), 2018, Kindle edition.

Famine, Fenians and Freedom, 1830-1882, (Authoring History), 2018. Kindle edition.

Disrupting the British World, 1600-1980, (Authoring History), 2018, Kindle edition.

Britain 1780-1945: Society under Pressure, (Authoring History), 2018, Kindle edition.

Britain 1780-1945: Reforming Society, (Authoring History), 2018, Kindle edition.

Robert Guiscard: Portrait of a Warlord, (Authoring History), 2016, 2018, Kindle edition.

Roger of Sicily: Portrait of a Ruler, (Authoring History), 2016, 2018, Kindle edition.

People and Places: Britain 1780-1950, (Authoring History), 2017, 2018, Kindle edition.

Breaking the Habit: A Life of History, (Authoring History), 2016, 2018, Kindle edition.

2019

Sunday 8 July 2018

From Peace to Victory: Amiens to Waterloo 1802-1815

The Peace of Amiens, negotiated by Hawkesbury (later Lord Liverpool) and Cornwallis and ratified by Parliament in May 1802, received a poor press from contemporaries and subsequently from historians. The surrender of Austria deprived Britain of any leverage in Europe and Addington accepted terms which recognised French predominance on the continent and agreed to the abandonment of all overseas conquests. Grenville and Windham regarded these concessions as a disgrace and refused to give the ministry further support. This opened a split between them and Pitt, who was still prepared to give Addington assistance. Viewed simply in territorial terms Amiens was disastrous but Addington and his ministers saw it as a truce, not a final solution. Britain had been at war for nine years and Addington, previously Speaker of the House of Commons, was fully aware of growing pressures from MPs and from the nation at large for peace. Canning, one of the most vehement critics of the Peace, willingly admitted that MPs were in no mood to subject its terms to detailed scrutiny and that they would have ratified almost anything.

Addington

Amiens to Trafalgar 1802-1805

In the twelve months between Amiens and the inevitable renewal of the war, Addington made military and fiscal preparations that placed Britain in a far stronger position than it had been in 1793. British naval and military strength was not run down. The remobilisation of the fleet proceeded well in 1803. Addington retained a regular army of over 130,000 men of which 50,000 were left in the West Indies to facilitate the prompt occupation of the islands given back in 1802 when the need arose. 81,000 men were left in Britain that, with a militia of about 50,000, provided a garrison far larger than anything Napoleon could mount for invasion in 1803. The 1803 Army of Reserve Act produced an additional 30,000 men. He revived the Volunteers, backed by legislation giving him powers to raise a levy en masse. This raised 380,000 men in Britain and 70,000 in Ireland and by 1804, they were an effective auxiliary force. Reforms by the Duke of York improved the quality of officers and in 1802, the Royal Military College was set up. Addington improved Pitt’s fiscal management of the war in his budgets of 1803 and 1804 by deducting income tax at source. This was initially set at a shilling and raised by Pitt in 1805 at 1/3d, in the pound on all income over £150. Fox, who bitterly denounced Pitt’s 25 per cent increase in 1805, had now to defend a further 60 per cent increase the following year. Once war was renewed in 1803, Addington adopted a simple strategy of blockading French ports. The navy swept French commerce from the seas. Colonies recently returned to France and her allies were reoccupied. He sought allies on the continent who were willing to resist French expansion.

Continuity of strategy

From 1803 until about 1810, there was little difference in Britain’s strategy to that employed in the 1790s or its level of success. Addington gave way to Pitt in April 1804. Napoleon recognised that final victory depended on the conquest of Britain and during early 1805, preparations were made for an invasion. To succeed he needed to control the Channel and to prevent the formation of a European coalition against France. He failed on both counts. The destruction of a combined Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar in October 1805 denied Napoleon naval supremacy and the hesitant moves of Russia and Austria against him meant that troops intended for invasion had to be diverted. Between late 1805 and 1807, France confirmed its military control of mainland Europe. The Third Coalition was quickly overwhelmed in 1806 and 1807. Austria was defeated at Ulm and Austerlitz in October and December 1805 respectively and in January 1806 Austria made peace at Pressburg. Prussia, which had remained neutral in 1805, attempted to take on France single-handed and was defeated at Jena in October 1806; Russia, after its defeat at Friedland, made peace at Tilsit in 1807. Britain once again stood alone.

‘Economic warfare’

With the prospect of successful invasion receding as a means of defeating Britain, Napoleon turned to economic warfare. The Berlin Decree (November 1807) threatened to close all Europe to British trade. This was not new. Both Pitt and the Directory had issued decrees aimed at dislocating enemy trade and food imports. The difference between Napoleon’s continental system and the attempts in the 1790s was one of scale. Between 1807 and 1812, France’s unprecedented control of mainland Europe meant that British shipping could be excluded from the continent. In practice, however, there were major flaws in Napoleon’s policy. It was impossible to seal off Europe completely from British shipping. Parts of the Baltic and Portugal remained open and in 1810 Russian ports were reopened to British commerce. In the face of French agricultural interests, Napoleon did not ban the export of wines and brandies to Britain and during the harvest shortages of 1808-1810, he allowed the export of French and German wheat under license. Most importantly, he had no control over Britain’s trade with the rest of the world and it was to this that Britain increasingly looked. Though the Continental System and particularly Britain’s Orders in Council were blamed for economic crisis in 1811-1812 by both manufacturers and the Whigs, it has been suggested that a better explanation can be found in industrial overproduction and speculation in untried world markets. Napoleon failed to achieve an economic stranglehold because he did not have naval supremacy and because Britain’s economic expansion was directed at non-European markets. The British blockade inflicted far more harm on France, whose customs receipts fell by 80 per cent between 1807 and 1809 than exclusion from Europe ever did to Britain.

The British response to the creation of the Continental System came in the form of Orders in Council. In January 1807, the ‘Ministry of all the Talents’ banned any sea borne trade between ports under French control from which British shipping was excluded. To avoid unduly antagonising the United States trade by neutral shipping from the New World to French-controlled ports was unaffected. The Portland ministry took a harder line. Under pressure from Spencer Perceval, the Chancellor of the Exchequer far more strict Orders were issued in November and December 1807. This extended exclusion to all shipping from French-controlled ports, paying transit duties in the process. The major purpose of the Orders was to dislocate European commerce and as a result create discontent with the Napoleonic regime. Success was achieved at the cost of further deterioration in relations with the United States. Demand for British goods meant that trade was largely uninterrupted until America passed a Non-Importation Act in 1811. British exports to her largest single market plummeted from £7.8 million in 1810 to £1.4 million in 1811. There was a corresponding reduction in imports of raw cotton, which was 45 per cent lower in 1812-1814 than in 1809-1811. The Anglo-American war of 1812-1814 was fought largely about the Great Lakes, since the primary objective of the American ‘hawks’ was the conquest of Upper Canada. The New England states opposed the war vigorously and had the Orders in Council been withdrawn a few weeks earlier it would probably not have been approved by Congress. Little was achieved militarily and the most famous incident of the war, the repulse of a British attack on New Orleans, was fought a month after the war ended but before news of the Peace of Ghent reached America. The peace settled nothing. None of the original causes of the war, for example, the boundaries between the United States and Canada or maritime rights, received any mention.

Total victory 1808-1815

The final phase of the war began in 1808 when Napoleon attempted to exchange influences for domination in the Iberian Peninsula. Nationalist risings in Spain against the installation of Napoleon’s brother Joseph as king and anti-French hostility in Portugal, which had been annexed the previous autumn, prompted Castlereagh, Secretary of War for the Colonies, to send 15,000 troops in support. This approach conformed to the strategy used since 1793 of offering limited armed support to the opponents of France. In the next five years, British troops, at no time more than 60,000 strong, led by Arthur Wellesley (created Viscount Wellington in 1809) and his Portuguese and Spanish allies fought a tenacious war with limited resources. Wellington’s victory at Vimeiro in August 1808 was followed by the Convention of Cintra, negotiated by his superior, which repatriated the French troops and set Portugal free. By the time, Wellington returned to the Peninsula in April 1809, it seemed that this campaign was to be no more successful than the Walcheren expedition to the Low Countries was to prove later that year.

The Peninsula campaign drained Napoleon’s supply of troops that he had to divert from central Europe. Calling the war the ‘Spanish Ulcer’ was no understatement. Wellington gradually wore down French military power and it was from the Peninsula that France was first invaded when Wellington crossed the Pyrenees after his decisive victory at Vitoria in August 1813. Napoleon’s position in Europe was weakened by the unsuccessful and costly Russian campaign of 1812 and by the spring of 1813, the British government was absorbed in creating a further anti-French coalition. The Treaty of Reichenbach provided subsidies for Prussia and Russia. Separately negotiated treaties, usually under French military duress, had been a major problem of the three previous attempts at concerted allied action. Castlereagh, now foreign secretary, saw keeping the allies together long enough to achieve the total defeat of France as one of his primary objectives. Austria was at first unwilling to enter the coalition, fearing the aggressive aspirations of Russia as much as those of France. Castlereagh knew that a general European settlement was impossible without total victory. When he arrived in Basle in February 1814 French troops were everywhere in retreat--Napoleon had been defeated in the three-day ‘Battle of the Nations’ at Leipzig the previous October and Wellington had invaded south-west France--but the allies were no more trusting of each other’s motives. Castlereagh demonstrated his skills as a negotiator and achieved the Treaty of Chaumont in March by which the allies pledged to keep 150,000 men each under arms and not to make a separate peace with France. Napoleon’s abdication and exile to Elba in 1814 allowed Castlereagh to implement his second objective: the redrawing of the map of Europe to satisfy the territorial integrity of all nations, including France. The Congress of Vienna of 1814-1815, within limits, achieved this. Napoleon’s final flourish in 1815 that ended at Waterloo made no real difference.

Saturday 26 May 2018

Why did Britain not win the war with France 1793 and 1802?

[1] The First Coalition against France was signed in February 1793. It consisted of Britain, Austria, Prussia and Holland. Spain and Sardinia also entered the coalition strengthening Pitt’s belief that the war would not last long.[2] The Second Coalition consisted of Britain, Russia, Austria, Turkey, Portugal and Naples and proved to have even fewer unifying features than the first.[3] Britain had fought a long war with France for dominance in India culminating in the battle of Plassey in 1757 when Robert Clive defeated a combined Indian-French army. Some French settlements remained though they were quickly taken in 1793-1794.[4] The Caribbean was always a graveyard of troops and seamen largely from malaria and yellow fever. Between 1793 and 1801, the British army sent 89,000 men to the Caribbean and lost 70 per cent of them. The total loss for army, navy and transport crew was probably over 100,000.[5] Tipu ‘the Lion’ of Mysore was the cruel, yet enlightened ruler of Mysore. He was strongly pro-French.[6] Horatio, Lord Nelson (1759-1805) was the most successful and popular naval figure during the war. His victories at Aboukir Bay in 1798, Copenhagen in 1801 and Trafalgar in 1805 played a central role in preserving British freedom. His death at Trafalgar achieved mythic proportions.

Wednesday 4 April 2018

What were the social and economic effects of the Famine?

The ‘Great Famine’ began unexpectedly in the late summer of 1845. By September, potatoes were rotting in the ground and within a month blight was spreading rapidly. Three-quarters of the country’s crop, the chief food for some three million people was wiped out. The following year blight caused a total crop failure. In 1847, the blight was less virulent but in 1848 a poor grain harvest aggravated the situation further. 1848 proved to be the worst year in terms of distress and death during the whole history of the Great Famine. Both 1849 and 1850 saw blight, substantial in some counties, sporadic in others.

Why was there famine?

Famine caused by potato blight was nothing new to Ireland. There had been failures in 1739, 1741, 1801, 1817 and 1821. In 1741, perhaps 400,000 people died because of famine. The Great Famine in the 1840s was only one demographic crisis among many but most historians regard it as a real turning point in Irish history. It was simply a disaster beyond all expectations and imagination.

Contemporaries and historians have considerable difficulty in explaining why the Famine took place. It is, however, generally agreed that the structure of the Irish economy and especially its system of land tenure played a significant part. Most of the cultivated land in Ireland in the 1840s was in the hands of Protestant landowners. Estates were regarded as sources of income for these landowners, many of them absentees in England rather than long-term investments. This led to a failure to invest in Irish farming. Tenants were unable to invest in their land because of high rents. Where improvement in farming did occur in Ireland, it proved very profitable. Irish agriculture promised returns of between 15 and 20 per cent compared to 5 to 10 per cent yields in England. There was insufficient land available to satisfy demand, despite the conclusion of the Devon Commission that over 1.5 million acres of land suitable for tillage was uncultivated. This led to the division and sub-division of land. By 1845, a quarter of all holdings were between one and five acres, 40 per cent were between five and fifteen acres and only seven per cent over thirty acres. This created under-employment and forced many of the labourers to become migrant workers in England for part of the year. They became navvies for road building, canal digging and railway construction. Many turned seasonal migration into permanent settlement and were largely involved in work English people found dirty, disreputable or otherwise disagreeable--jobs like petty trading, keeping lodging-houses and beer-houses. Inadequate investment meant that Irish industrialisation could not provide the employment necessary to absorb its growing population.

The potato made the division and sub-division of land possible. It was easy to grow even in poor soil and produced high yields. Two acres of land could provide enough potatoes for a family of five or six to live on for a year. Potatoes could also be used to feed pigs and poultry. Subsistence on the potato allowed tenants to grow wheat and oats to pay their rent. The precise relationship between the potato and population growth in Ireland is difficult to establish. It is clear that there was a dramatic rise in Irish population in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The high birth rate and the early age of marriage were largely responsible for dramatic growth. Between 1780 and 1841, Ireland’s population increased from about five million to over eight million people, despite the emigration of one and a half million people in the decades after Union. This placed even greater pressure on land and greater reliance on the potato.

How did the British government react?

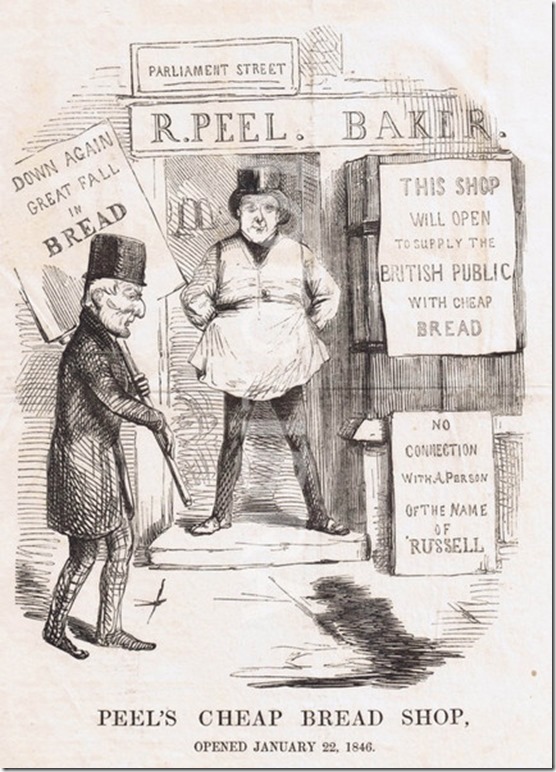

Peel’s response was rapid and, within limits, imaginative. The crisis convinced him finally of the necessity for dismantling the Corn Laws but he realised that this would, because of its contentious nature, take time. Immediate solutions were needed. In November 1845, a Special Commission was established to co-ordinate relief efforts. It did two things. First, work was needed so that labourers could afford to buy food. The government established public work schemes but on a much larger scale than before. These were the boom years of Irish railway construction. Food had also to be kept at a level that prevented profiteering. £185,000 was spent on supplies, chiefly Indian meal. These measures, however, only met the immediate crisis. Lord John Russell succeeded Peel in mid-1846 but he lacked Peel’s Irish experience. Economy and efficiency replaced Peel’s more humane policy. The full extent of the Famine was seriously underestimated in official circles. The problem, however, was not the shortage of food in Ireland--between September 1846 and July 1847 five times as much grain was imported as was exported--but of ensuring that those in need had access to that food. The failure was one of awareness, not compassion.

What were the consequences of the Famine?

Between 1841 and 1851, the population of Ireland fell from over 8 million to some 6.5 million. Emigration accounted for perhaps 1.5 million and became an accepted part of Irish life. This leaves about a million deaths as a result of the Famine. Actual starvation rarely caused death but weakened people sufficiently for diseases like typhus and fever to take their toll. In early 1849, a serious outbreak of cholera added to the problem. The impact of famine was felt differently in both regional and social terms. Western and south-western counties were hardest hit. Counties on the east coast, where food could be more easily imported, were least affected. The north-east did not suffer a crisis, despite its high density of population, because of the more industrial nature of its economy. But it was not unaffected. Many disease-ridden migrants crowded into Belfast, where poor living conditions helped spread disease, but this was a public health not an economic problem.

Labourers and small farmers were the chief victims of the Famine. In 1841, 71.5 per cent of holdings were less than 15 acres but by 1851 the figure was 49.1 per cent. There was a consequent increase in the number of holdings over 15 acres from 18.5 to 50.9 per cent. Livestock farming expanded encouraged by attractive prices in Britain and by reductions in transport costs. In 1851, the agricultural economy was apparently still in a state of crisis: the potato had lost its potency, low agricultural prices gave little promise of recovery to those who had survived, and slightly larger holdings hardly made up for increased Poor Law rates. But from the 1850s change was rapid. Livestock increased in value and numbers, arable farming declined slowly and tenant farmers, whose numbers remained relatively stable for the next fifty years, enjoyed some prosperity.

The Famine marked a watershed in the political history of modern Ireland. The Repeal Association of O’Connell was dead. Young Ireland made their separatist gesture in the abortive rising of 1848. A sense of desolation, growing sectarian divisions, the rhetoric of genocide and the re-emergence of some form of national consciousness eventually led to the emergence of a movement dedicated to the independence of Ireland from English rule.

Wednesday 20 December 2017

Why did Corn Law repeal lead to the end of Peel’s government?

Relations between Peel and his backbenchers were strained from the early days of his ministry. Peel was insensitive to their interests of many Conservative MPs and made little attempt to court backbench opinion. He took the loyalty of Conservatives in Parliament for granted and was irritated when this was withheld. Peel managed his government but he made little effort to manage his party. Conservative whips warned Peel of the unpopularity of his 1842 Budget among Protectionists and 85 Conservatives failed to support him. Poor Law and factory reform also led to backbench discontent. These rebellions did not threaten Peel’s position in 1842 and 1843 but divisions between Peel’s government and his Protectionist MPs widened further.

In March 1844, 95 Tories voted for Ashley’s amendment to the Factory Bill and in June 61 Tories supported an amendment to the government proposal to reduce the duty on foreign sugar by almost half. Both amendments were carried and though Peel had little difficulty in reversing them his approach caused considerable annoyance. He threatened to resign if they refused to support him. Reluctantly they fell into line. Party morale was low in early 1845 and party unity was showing signs of terminal strain. On the Corn Laws, Peel pushed his party too far.

Arguments for repeal

By 1845, it was increasingly recognised that repeal was in the national interest. The Corn Laws were designed to protect farmers against the corn surpluses, and hence cheap imports, of European producers. By the mid-1840s, there was a widespread shortage of corn in Europe and Peel reasoned that British farmers had nothing to fear from repeal because there were no surpluses to flood the British market. The nation would benefit, the widespread criticism of the aristocracy would be removed and the land-owning classes were unlikely to suffer.

By 1841, Peel had, in fact, recognised that the Corn Laws would eventually have to be repealed. The moves to free trade in the 1842 and 1845 Budgets were part of this process. Since corn was one of the most highly valued import Peel needed to include it. He argued that tariff reform did not mean abandoning protection for farming, but he called for fair, rather than excessive protection. In 1842, Peel reduced the levels of duty paid under the existing sliding scale on foreign wheat from 28s 8d to 13s per quarter when the domestic price of what was between 59s and 60s. The Whigs favoured a fixed duty on corn but were defeated and the expected protectionist Tory rebellion did not occur. The following year, the Canadian Corn Act admitted Canadian imports at a nominal duty of 1s a quarter. Peel argued that this was a question of giving the colonies preferential treatment rather than freer trade. Protectionist backbenchers were not convinced and though their amendments were easily defeated, they demonstrated a growing concern about the direction of Peel’s tariff policies.

Yet, Peel did not announce his conversion to repealing the Corn Laws until late in 1845. Why? There are different possible explanations for his decision. Peel had accepted the intellectual arguments for free trade in the 1820s supporting the commercial policies put forward by Huskisson. His later thinking was influenced by Huskisson’s view that British farmers would eventually be unable to supply the needs of Britain’s growing population and that imports of foreign grain would be essential. In which case, the repeal of the Corn Laws would then be inevitable. Peel may have accepted this but he was the leader of a Protectionist party. According to this view, Peel intended to abandon its commitment of agricultural protection before the General Election due in 1847 or 1848 with repeal following during the next Parliament, probably in the early 1850s. This might have given Peel the time to convince his own MPs.

Time ran out when famine broke out in Ireland. By October 1845, at least half of the Irish potato crop had been ruined by blight and this led to a major subsistence crisis since large numbers of people depended entirely on the potato for food. If the government was to act quickly to reduce the worst effects of famine, every barrier to the efficient transport of food needed to be removed. The most obvious barrier was the Corn Laws and this meant either their suspension or abolition to open Irish ports to unrestricted grain imports. Suspending the Acts was not a viable option as Peel maintained it would be impossible to reconcile public opinion to their re-imposition later. However, there is a problem with this view. The failure of the potato crop meant that those Irish did not have any way of earning the money to pay for imported corn, even if it was sold more cheaply. The £750,000 spent by Peel’s government on public work projects, cheap maize from the United States and other relief measures were of far more practical value to Ireland than the repeal of the Corn Laws. Peel used the opportunity provided by the Famine to introduce a policy on which he had already made up his mind and the crisis merely accelerated this process.

Peel disapproved of extra-parliamentary pressure and viewed the lobbying of the Anti-Corn Law League with considerable suspicion. The success of the League, especially between 1841 and 1844, may have persuaded Peel not to move quickly to repeal. He saw it as his duty to act in the national interest and did not want to be accused of acting under pressure. The activities of the League threatened to divide propertied interests and Peel saw that social stability was essential for economic growth. Giving in to the League was an unacceptable political option. Peel was also critical of the League’s propaganda especially its language of class warfare. The strident, anti-aristocratic attacks by the League and the creation of a Protectionist Anti-League raised the spectre of commercial and industrial property pitted against agricultural property. This, Peel believed, would significantly weaken the forces of property against those agitating for democratic rights. However, Peel recognised that the Anti-Corn Law League might exploit the crisis in Ireland. Repeal was therefore a pre-emptive strike designed to take the initiative away from middle-class radicals and as a result help to maintain the landed interest’s control of the political system.

The politics of repeal

Peel told his cabinet in late 1845 that he proposed repealing the Corn Laws outlining that it was in the national interest to do so. This was too sophisticated for the Protectionists. For small landowners and tenant farmers, the most vocal supporters of protection, repeal meant ruin. Peel’s argument that free trade would offer new opportunities for efficient farmers made little impact. Although only Viscount Stanley and the Duke of Buccleuch resigned on the issue, Peel nonetheless felt that this was sufficient for him to resign.

He hoped that Lord John Russell and the Whigs would form a government, pass repeal through Parliament and perhaps allow him to keep the Conservative Party together. Lord John Russell had recently announced his conversion to repeal in his ‘Edinburgh Letter’ in December 1845 but was unwilling to form a minority administration. This meant that Peel had to return to office. Predictably, repeal passed its Third Reading in the Commons in May 1846. The Whigs voted solidly for the bill but only 106 Tories voted in favour of repeal compared to 222 against. The great landowners voted solidly for repeal as they recognised that it did not threaten their economic position. The bulk of the opposition came from MPs representing the small landowners. Retribution was swift. In June 1846, sufficient Protectionists voted with the Whigs on an Irish Coercion Bill to engineer Peel’s resignation. He did not hold office again dying in 1850 after a horse riding accident.