Relations between Peel and his backbenchers were strained from the early days of his ministry. Peel was insensitive to their interests of many Conservative MPs and made little attempt to court backbench opinion. He took the loyalty of Conservatives in Parliament for granted and was irritated when this was withheld. Peel managed his government but he made little effort to manage his party. Conservative whips warned Peel of the unpopularity of his 1842 Budget among Protectionists and 85 Conservatives failed to support him. Poor Law and factory reform also led to backbench discontent. These rebellions did not threaten Peel’s position in 1842 and 1843 but divisions between Peel’s government and his Protectionist MPs widened further.

In March 1844, 95 Tories voted for Ashley’s amendment to the Factory Bill and in June 61 Tories supported an amendment to the government proposal to reduce the duty on foreign sugar by almost half. Both amendments were carried and though Peel had little difficulty in reversing them his approach caused considerable annoyance. He threatened to resign if they refused to support him. Reluctantly they fell into line. Party morale was low in early 1845 and party unity was showing signs of terminal strain. On the Corn Laws, Peel pushed his party too far.

Arguments for repeal

By 1845, it was increasingly recognised that repeal was in the national interest. The Corn Laws were designed to protect farmers against the corn surpluses, and hence cheap imports, of European producers. By the mid-1840s, there was a widespread shortage of corn in Europe and Peel reasoned that British farmers had nothing to fear from repeal because there were no surpluses to flood the British market. The nation would benefit, the widespread criticism of the aristocracy would be removed and the land-owning classes were unlikely to suffer.

By 1841, Peel had, in fact, recognised that the Corn Laws would eventually have to be repealed. The moves to free trade in the 1842 and 1845 Budgets were part of this process. Since corn was one of the most highly valued import Peel needed to include it. He argued that tariff reform did not mean abandoning protection for farming, but he called for fair, rather than excessive protection. In 1842, Peel reduced the levels of duty paid under the existing sliding scale on foreign wheat from 28s 8d to 13s per quarter when the domestic price of what was between 59s and 60s. The Whigs favoured a fixed duty on corn but were defeated and the expected protectionist Tory rebellion did not occur. The following year, the Canadian Corn Act admitted Canadian imports at a nominal duty of 1s a quarter. Peel argued that this was a question of giving the colonies preferential treatment rather than freer trade. Protectionist backbenchers were not convinced and though their amendments were easily defeated, they demonstrated a growing concern about the direction of Peel’s tariff policies.

Yet, Peel did not announce his conversion to repealing the Corn Laws until late in 1845. Why? There are different possible explanations for his decision. Peel had accepted the intellectual arguments for free trade in the 1820s supporting the commercial policies put forward by Huskisson. His later thinking was influenced by Huskisson’s view that British farmers would eventually be unable to supply the needs of Britain’s growing population and that imports of foreign grain would be essential. In which case, the repeal of the Corn Laws would then be inevitable. Peel may have accepted this but he was the leader of a Protectionist party. According to this view, Peel intended to abandon its commitment of agricultural protection before the General Election due in 1847 or 1848 with repeal following during the next Parliament, probably in the early 1850s. This might have given Peel the time to convince his own MPs.

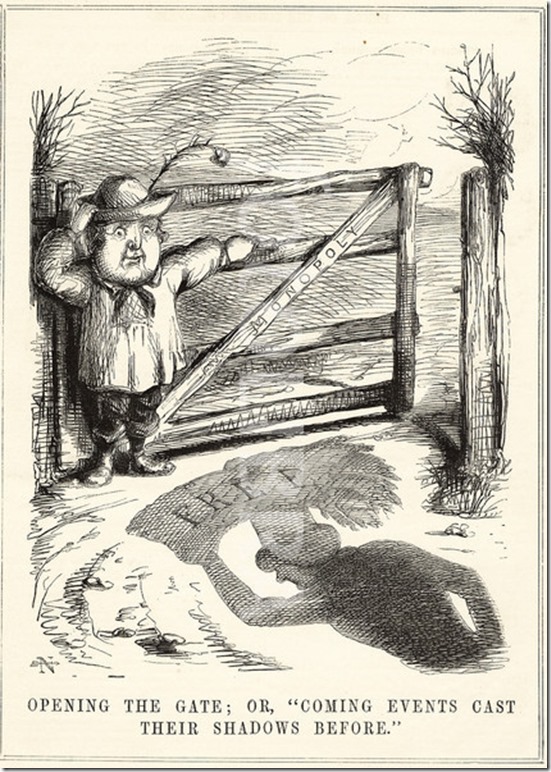

Time ran out when famine broke out in Ireland. By October 1845, at least half of the Irish potato crop had been ruined by blight and this led to a major subsistence crisis since large numbers of people depended entirely on the potato for food. If the government was to act quickly to reduce the worst effects of famine, every barrier to the efficient transport of food needed to be removed. The most obvious barrier was the Corn Laws and this meant either their suspension or abolition to open Irish ports to unrestricted grain imports. Suspending the Acts was not a viable option as Peel maintained it would be impossible to reconcile public opinion to their re-imposition later. However, there is a problem with this view. The failure of the potato crop meant that those Irish did not have any way of earning the money to pay for imported corn, even if it was sold more cheaply. The £750,000 spent by Peel’s government on public work projects, cheap maize from the United States and other relief measures were of far more practical value to Ireland than the repeal of the Corn Laws. Peel used the opportunity provided by the Famine to introduce a policy on which he had already made up his mind and the crisis merely accelerated this process.

Peel disapproved of extra-parliamentary pressure and viewed the lobbying of the Anti-Corn Law League with considerable suspicion. The success of the League, especially between 1841 and 1844, may have persuaded Peel not to move quickly to repeal. He saw it as his duty to act in the national interest and did not want to be accused of acting under pressure. The activities of the League threatened to divide propertied interests and Peel saw that social stability was essential for economic growth. Giving in to the League was an unacceptable political option. Peel was also critical of the League’s propaganda especially its language of class warfare. The strident, anti-aristocratic attacks by the League and the creation of a Protectionist Anti-League raised the spectre of commercial and industrial property pitted against agricultural property. This, Peel believed, would significantly weaken the forces of property against those agitating for democratic rights. However, Peel recognised that the Anti-Corn Law League might exploit the crisis in Ireland. Repeal was therefore a pre-emptive strike designed to take the initiative away from middle-class radicals and as a result help to maintain the landed interest’s control of the political system.

The politics of repeal

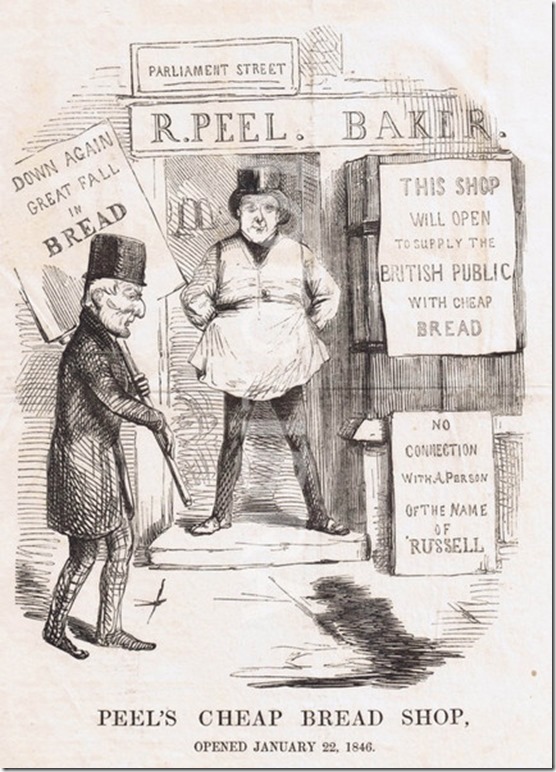

Peel told his cabinet in late 1845 that he proposed repealing the Corn Laws outlining that it was in the national interest to do so. This was too sophisticated for the Protectionists. For small landowners and tenant farmers, the most vocal supporters of protection, repeal meant ruin. Peel’s argument that free trade would offer new opportunities for efficient farmers made little impact. Although only Viscount Stanley and the Duke of Buccleuch resigned on the issue, Peel nonetheless felt that this was sufficient for him to resign.

He hoped that Lord John Russell and the Whigs would form a government, pass repeal through Parliament and perhaps allow him to keep the Conservative Party together. Lord John Russell had recently announced his conversion to repeal in his ‘Edinburgh Letter’ in December 1845 but was unwilling to form a minority administration. This meant that Peel had to return to office. Predictably, repeal passed its Third Reading in the Commons in May 1846. The Whigs voted solidly for the bill but only 106 Tories voted in favour of repeal compared to 222 against. The great landowners voted solidly for repeal as they recognised that it did not threaten their economic position. The bulk of the opposition came from MPs representing the small landowners. Retribution was swift. In June 1846, sufficient Protectionists voted with the Whigs on an Irish Coercion Bill to engineer Peel’s resignation. He did not hold office again dying in 1850 after a horse riding accident.

No comments:

Post a Comment