The question of loyalty has been important over the last few

days in Westminster and it seems tome to represent the growing dysfunction at

the heart of both Conservative and Labour parties. For the Conservatives it is

the long-running schism between those who want to stay in Europe and those who

do not while for Labour, it’s arguably the even longer battle between the left

and the centre for control of the party.

Ken Livingstone, who is co-chairing Labour's review of

Trident, has insisted Jeremy Corbyn was right to get rid of Michael Dugher and

Pat McFadden, saying: ‘You can't have shadow team going on telly and slagging

off Jeremy.’ Why ever not? This is precisely what Jeremy did on many occasions

during his decades on the backbenches. The outcome of what must be the longest

reshuffle in history has been two shadow ministers being sacked and Maria Eagle

being moved from defence to culture and Hilary Benn coming to an ‘agreement’

that, although he may disagree in private, he will toe the party line in public,

something that his ‘friends’ appear to deny. Jeremy’s calls for greater

discussion and democracy within the party—something he trumpeted during his

election campaign and subsequently—is beginning to look somewhat tattered. This

may have been a credible stance when you are oppositionist in attitude but it is

increasingly becoming obvious that it is not a credible position to take in

opposition. Of necessity, Jeremy needs to be seen as the leader of the

opposition not leader of the oppositionists and in that respect sacking Shadow

Cabinet ministers for ‘disloyalty’ is perfectly logical. This does, however,

raise questions about what ‘democracy’ means in the Labour Party today and it

increasingly appears that it is Jeremy who is the fount of all democratic

wisdom, a reflection of his oppositionist career. What I find interesting in

the attitude of what is increasingly seen by Labour as an anti-Corbyn

‘commentariat’ is that their focus is almost exclusively on what is happening in

Westminster rather than in the country. How far, for instance, have the

Corbynistas been able to influence the direction and position of local branches

of the Labour Party? This is something that appears little in the media and yet

surely it is at least as important, and arguably more important, than the

shenanigans in Westminster. For Ralph Miliband, this was the source of his

‘parliamentary socialism’.

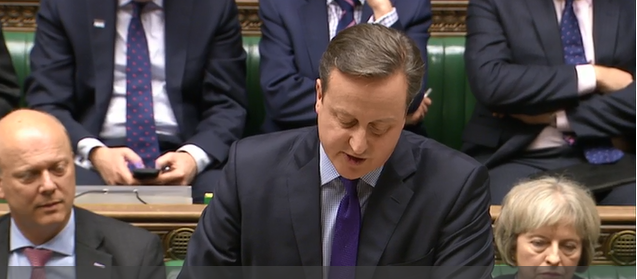

This morning Chuka Umunna has described David Cameron’s decision to allow

ministers to campaign for either side in the EU referendum once a deal is

reached on the UK’s relationship with the EU as ‘fairly ludicrous’. Yet this is

precisely what Harold Wilson did with his divided Cabinet in 1975. Without this

relaxation of collective responsibility, there would almost certainly have been

resignations so the Prime Minister’s decision removes one of many possible

problems those in favour of staying in have removed. It was a purely practical

solution to a problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment