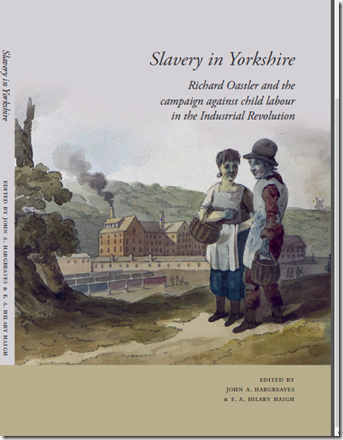

John A. Hargreaves and E. A. Hilary Haigh, (eds.)

Slavery in Yorkshire: Richard Oastler and the campaign against child labour in the Industrial Revolution

(University of Huddersfield), 2012

238pp., rrp £24 paper , ISBN 978-1-86218-107-6. The book is also available at £20 from www.store.hud.ac.uk.

In Kirkheaton churchyard near Huddersfield there is a fifteen-foot stone obelisk topped by a flame that commemorates ‘The dreadful fate of 17 children who fell unhappy victims to a raging fire at Mr Atkinson’s factory at Colne Bridge, February 14th 1818.’ All the dead were girls; the youngest nine, the oldest eighteen. The fire started when at about 5 am a boy aged ten was sent downstairs to the ground floor card room to collect some cotton rovings. Instead of taking a lamp, he took a candle that ignited the cotton waste and fire spread quickly through the factory turning it into a raging inferno. The children were trapped on the top floor when the staircase collapsed. The entire factory was destroyed in less than thirty minutes and the boy who had inadvertently started the fire was the last person to leave the building alive. It is not surprising that child labour and the need to regulate it became a national issue in the early 1830s. There had been factory acts in 1802 and 1819 and further agitation between 1825 and 1831 but the legislation was too limited in scope and its enforcement proved difficult. There were, for instance, only two convictions while the 1819 Act operated. It was at this stage that Richard Oastler, a Tory land steward from Huddersfield, burst upon the scene when his celebrated letter on ‘Yorkshire Slavery’ was published in the Leeds Mercury on 16 October 1830.

It is over sixty years since Cecil Driver published his study of Richard Oastler and fifty years since Ward’s study of the factory movement in the twenty years after 1830 appeared. This excellent volume, a fitting conclusion to the University of Huddersfield Archives’ Heritage Lottery-funded Your Heritage project, re-examines Oastler’s impact and draws parallels between the campaign to abolish transatlantic slavery and the campaign to restrict the use of child labour in Britain. Written by some of Yorkshire’s leading historians, the collection of essays provides a rounded assessment of the contribution of Richard Oastler to both the emancipation of children from the horrors of factory labour and the broader emancipation of society from the evils of slavery whether in Britain or in its Empire. The book is introduced by University of Huddersfield historian and Pro-Vice Chancellor Professor Tim Thornton and the foreword is from the Methodist minister Revd Dr Inderjit Bhogal OBE, who chaired the initiative Set All Free that marked the bi-centenary of the act to abolish the transatlantic slave trade. The volume begins with an elegantly written introduction by John A. Hargreaves who positions Oastler and the subsequent chapters within the context of the four decades from the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 and the passage of the Ten Hours Act for factory workers in 1847. This is followed by James Walvin, the doyen of the abolition movement, on William Wilberforce, Yorkshire and the campaign to end transatlantic slavery from its inception in 1787 to the end of the apprenticeship system in 1838. It is a succinct, synoptic analysis not only on what happened and why but also an acute critique of the prevailing historiography especially in its discussion of the impact of the abolition movement on reforming movements from factory reform to Chartism. It was Oastler who maintained that the cause of anti-slavery and Chartism were ‘one and the same’.

The remaining chapters focus on Oastler and provide important reappraisals of different aspects of his life. D. Colin Dews examines Oastler’s Methodist background between 1789 and 1820 demonstrating that his association with evangelicalism stimulated and sustained his commitment to the ten-hour movement while John Halstead explores the Huddersfield Short Time Committee and its radical associations between c1820 and 1876, a particularly valuable discussion of generational differences with Huddersfield radicalism. Edward Royle considers the Yorkshire Slavery campaign between 1830 and 1832 through a close consideration of coverage in the regional press. Janette Martin examines Oastler’s triumphant return to Huddersfield in 1844 after he had served more than three years in jail for debt relating this to Oastler’s skills as an orator and the importance of processions to nineteenth century radicalism; for instance, John Frost’s equally triumphant return to Newport in 1856 after over a decade as a transported felon. The volume ends with a chapter reassessing Oastler and his impact on the factory movement and on radical politics more generally.

Oastler and other reformers may have been successful in their campaign for the ending of child labour but coerced labour remains an important problem in a global economy where labour costs need to be kept low to meet consumer demands for affordable products. The ‘Yorkshire Slavery’ that Oastler so eloquently exposed can still be seen not just in the developing world but, as recent cases of ‘slavery’ brought before the courts demonstrate, in Britain as well. This excellent volume, beautifully illustrated and presented by the University of Huddersfield Press shows not simply the contribution Oastler made to achieving a sense of childhood largely devoid of economic exploitation but that the campaign he initiated in late 1830 remains a campaign that has yet to be concluded. After nearly two centuries as a global community we have yet to eradicate economic inhumanity and exploitation for profit.

No comments:

Post a Comment