Ireland posed three problems in the period between the 1780s and the famines in the mid-1840s. First, there was the question of how Ireland should be governed. There was also the highly emotive question of the rights of the Catholic majority in Ireland. Finally, the nature of Ireland’s economic and social structure was brought into high relief by the disastrous events of the 1840s. In addition, events in Ireland had a profound effect on mainland politics.

Why was Ireland a problem for William Pitt?

Ireland was important to Pitt throughout his first ministry and led to his resignation in 1801. Three things were important. Pitt wanted to establish good relations with the Irish Parliament that had been given considerable legislative freedom in 1782. The loss of America in 1783 meant that Ireland took on a more important role in Britain’s trading empire. Finally, there were important security issues and after 1793, Pitt had to be wary of plans for a French invasion using Ireland as a base.

In the early 1780s, Ireland had a rapidly growing population of around four million. Most were Roman Catholic but it was the Anglo-Irish Protestant landowners[1] who controlled about eighty percent of the land. They were often absentee landlords and were bitterly resented by their Catholic tenants, who generally lived in poverty. This Protestant elite governed Ireland largely for its own benefit and strongly resisted interference from Britain. Relations between the Irish and Westminster Parliaments were strained throughout the eighteenth century. In the 1770s and 1780s, the Irish Parliament enthusiastically supported the Americans in their fight for independence turning Ireland into a pro-American colony on England’s doorstep.

Demands for parliamentary reform especially the campaign to open up Parliament to other forms of property besides land in the mid-1780s failed. The major reason for this was sectarian. Catholics had been deprived of their political rights in the late-seventeenth century and Protestants, who had more to lose, were unwilling to change this. Middle-class political identity had been created in the late 1770s and early 1780s but this had not led to an opening up of the political system. The Anglican ‘ascendancy’ was unwilling to share power with the middle-classes. The reforms of 1782-1783 led to a narrowing of the political elite in Ireland. Catholics were totally excluded from political power by the Penal Laws and Dissenters had only limited access.[2] No Presbyterians sat in the Dublin Parliament. Anglican landowners controlled parliamentary seats and this control increased dramatically after 1782. The result of the failure to take the reforms of 1782-1783 forward was an increasing polarisation of Irish politics between Catholics and Protestants and between those with access to power and those denied it.[3]

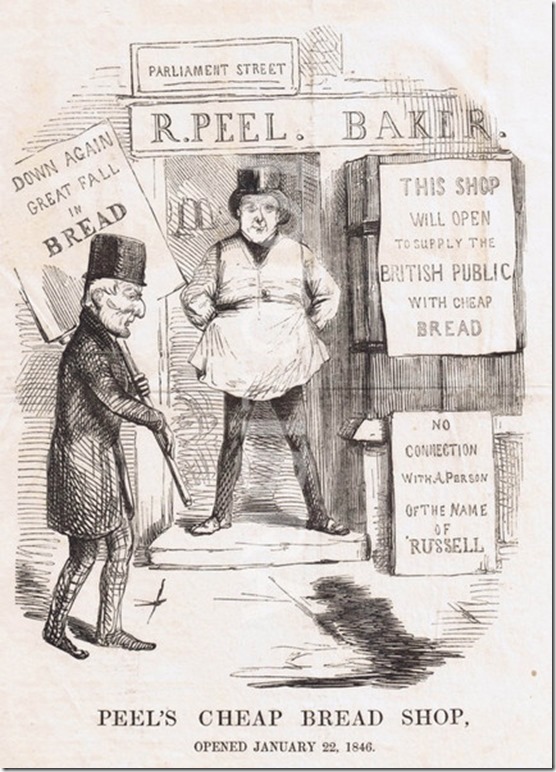

Politicians agreed on two things, both designed to prevent Ireland following the American colonies into independence. Ireland should have a significant amount of self-government and that it should have greater access to British markets. Pitt saw the second issue as a way of strengthening the British Empire as well as creating political stability. In 1785, he proposed free trade between England and Ireland. This, he maintained, would benefit Irish trade and, from its profits, a contribution could be made for the defence of the Empire. However, the Irish disliked the idea of contributing to imperial defence intensely drawing parallels with proposals to tax the American colonies in the 1760s. British manufacturers organised a vigorous campaign against the threat from Ireland especially to the woollen trade. Pitt had little choice but to withdraw his proposals. Despite this, Ireland’s trade with Britain increased significantly in the 1780s. Irish linen exports trebled between 1781 and 1792. During the 1780s, Pitt’s control over Irish politics was severely limited by the independent actions of the Dublin Parliament.

The effects of the French Revolution.

The French Revolution renewed demands for political and parliamentary reform. Pitt did not accept the view of the Dublin Parliament that the security of Ireland could be guaranteed only by continued Catholic oppression and he attempted to win over the Catholic gentry. In 1792, an Irish Catholic Relief Act freed Catholics from remaining disabilities relating to mixed marriages, education and the law. The following year they were given the same municipal and parliamentary franchise as Protestants. However, these concessions did little to improve their status and they were still debarred from membership of the Irish Parliament. These concessions were wrung out of an unwilling Irish Parliament and many in the Protestant Ascendancy felt betrayed. Their insecurity was reinforced by the actions of Earl Fitzwilliam, briefly Irish Chief Secretary in 1795. Fitzwilliam supported religious toleration and, having assured Pitt that he would not meddle with the Irish administration quickly began to do precisely that. Pitt had little choice but to recall him. Pitt’s reforms whetted the appetite of the more radical Irishmen but satisfied few. Protestant fears of eventual Catholic domination were heightened. Sectarian divisions were increased by measures designed to protect Ireland from invasion after the outbreak of war with Catholic France. Between 1793 and 1796 a Militia Act was passed, a new Protestant Yeomanry formed, an Insurrection Act that made oath-taking a capital offence became law and Habeas Corpus was suspended.

Irish reformers believed in Irish nationalism and more democratic institutions. Demands for reform straddled the religious divide and, during the 1790s support for Irish nationalism was non-sectarian. The two societies of ‘United Irishmen’ formed in late 1791 in Belfast (mostly Presbyterian and middle-class supporters) led by the lawyer Theobald Wolfe Tone and Dublin (mostly Catholic supporters) led by Napper Tandy, an ironmonger. Their non-sectarian approach had little appeal to most Irishmen. Secret societies of Catholic ‘Defenders’ and Protestant ‘Peep o’ Day Boys’ were responsible for rural atrocities. In September 1795, the Protestant Orange Order was formed dedicated to maintaining Protestant dominance at all costs. The failure of the Irish government to address the twin issues of ‘Emancipation’ and ‘parliamentary reform’ helped push Catholic and Protestant radicals closer together and encouraged the growth of more extreme demands.

The United Irishmen became increasingly nationalist in ideas appealing to all Irishmen, irrespective of religion to establish an independent Irish republic. Freedom from English rule appealed to both the middle-class radicals who had been denied access to political power and the Catholic peasantry who had largely economic grievances against Protestant landowners and the Anglican Church. Officially suppressed in 1794, the United Irishmen went underground and its leadership accepted French assistance to achieve revolution in Ireland. Bad weather prevented the French troops landing in December 1796 and British repression in Ulster in 1797 and around Dublin the following year significantly weakened the United Irishmen. The 1798 Rising was, in many respects, a prolonged and flabby failure. The United Irishmen was largely leaderless and its organisation was in disarray. It was unable to impose any real control over the rebellion when it finally began in late May. The result was a series of separate risings based largely on local grievances. The risings in Ulster and in the west of Ireland were very limited affairs. The Catholic rising in the south-east was, after some initial success, defeated at Vinegar Hill in June and the French landed too late to be of any real value. The rebellion lasted barely a month but some 30,000 people were killed or executed.

Union

The 1798 Rising convinced Pitt that the Dublin government could not keep Ireland loyal. Constitutional union of the two kingdoms became increasingly attractive and by June 1798, it was the only real option. Pitt believed that removing the remaining disabilities against Catholics was essential to ensure their support for union. In this, they faced opposition not only from the Protestant minority in Ireland and politicians in Westminster, but also from George III. Pitt decided that he would concentrate on getting the support of the Irish Parliament for union and would work for Catholic Emancipation once union had been achieved.

A narrow rejection of a Union Bill in Dublin in January 1799 was followed by a year of negotiation and bribery. Castlereagh as Chief Secretary was largely responsible for winning over public opinion. Critics denounced his activities as pure corruption but recent investigation has shown that the swing of Irish parliamentary opinion between 1799 and 1800 cannot be explained simply in these terms. The bulk of support for the 1800 Act came from MPs elected to the 60 seats that changed hands between the two votes on Union. More important was the inability of those opposed to Union to come up with any real alternative. This ensured the passage of the bill a year later. At Westminster, the Act of Union was approved with little difficulty and constitutional union occurred on 1 January 1801.[4]

Committed as Pitt and some of his colleagues were to Catholic Emancipation in 1800 they were unable to win over the king. In March 1801, Pitt resigned over the policy that he saw as necessary. Far from eliminating the Catholic question, Union merely pushed it more directly on to the British political scene. The Catholic community felt betrayed by the British government and soon became increasingly anti-unionist in attitude developing a sense of its own separate religious and national identity.

[1] Anglo-Irish Protestant landowners. Protestant control over the institutions of Ireland is known as the Protestant Ascendancy.

[2] Catholics had been deprived of their political rights. Most of the population of Ireland was Roman Catholics but their rulers were Protestant. Catholics were denied access to public offices, to ownership of land and to full involvement in the running of their country. The existence of disabilities against Catholics was used by the minority Protestants to maintain their political dominance

[3] Sectarian. Divisions in Ireland were based on religious belief and conflict generally followed the lines of religion. Catholics versus Protestants.

[4] In the Act of Union, the separate Irish Parliament disappeared. Each of the 32 Irish counties kept their two MPs. Two were given to Dublin and Cork and one to Dublin University and the 31 single-member Irish borough constituencies. This gave a total representation of 100 Irish MPs in the House of Commons. Twenty-eight Irish peers were elected for life to the House of Lords. One archbishop and three bishops spoke for the Irish Anglican Church. Irish peers, who were not representative peers, could sit in the Commons for mainland constituencies. The Anglican Churches of England and Ireland were united. The Act gave full equality of commercial rights and privileges though Castlereagh did secure twenty years’ protection for Irish textile manufacturers.